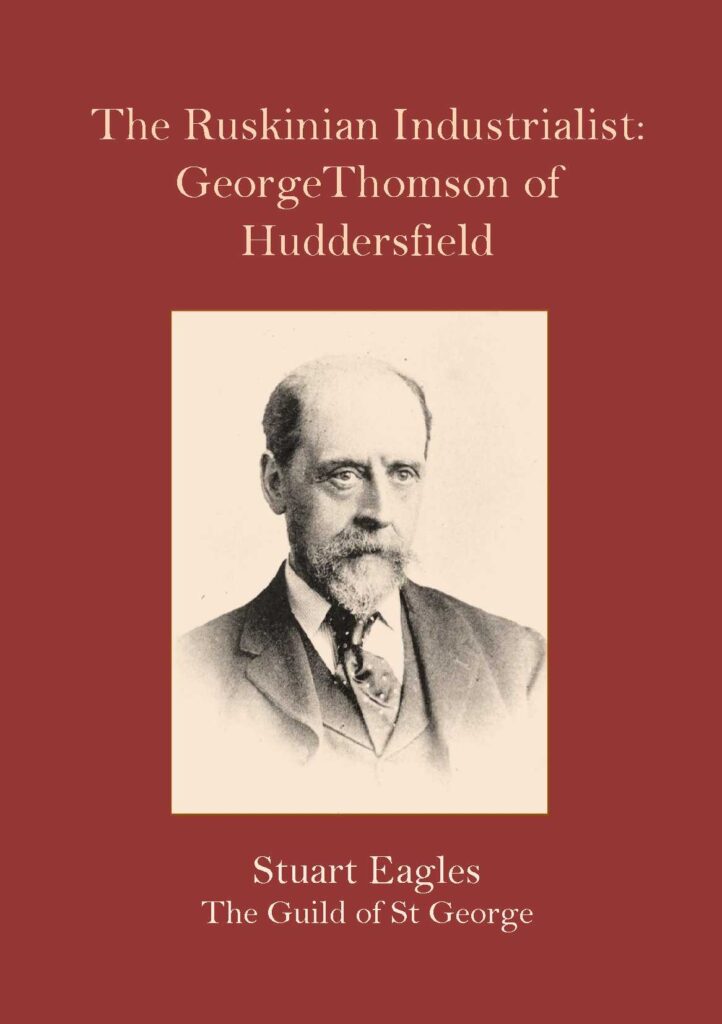

This is a year of Ruskinian anniversaries. Two of them—the 150th anniversary of John Ruskin’s Guild of St George, and the centenary of the death of the pioneering Yorkshire businessman, George Thomson—have prompted me to write, and the Guild to publish, a new pamphlet, The Ruskinian Industrialist: George Thomson of Huddersfield.

At 54 pages, it boasts 12 monochrome and two colour illustrations, only one of which has been published in recent years. It is based on extensive research in contemporary newspapers and archives, and includes many extracts from interviews given not only by Thomson but by his workers. The booklet costs £8 plus postage & packaging, and it can be ordered from the Guild of St George here.

George Thomson (1842-1921) was one of the few men of business who attempted to put John Ruskin’s ideas into practice. His courageous profit-sharing co-partnership experiment turned his father’s commercial woollen mill in Huddersfield into a thriving supplier of high-quality goods to the co-operative movement. Driven by a Ruskinian sense of justice, he earned the loyalty of his workers by giving them a stake in the company, employing them on highly favourable terms and providing exemplary working conditions.

As a distinguished local councillor who served as Huddersfield’s Mayor, Thomson promoted many good causes, especially in education and the arts. He was rewarded with the Freedom of the City. For nearly 40 years he helped guide Ruskin’s Guild of St George, eventually serving as Master.

A century after Thomson’s death, this study re-examines the life, work and legacy of this remarkable idealist and industrial pioneer.

There is an error to note. On Page26, the text reads, “Perhaps the most poignant testimony comes courtesy of Dr Thomas Armitage (1824-1890), the founder of what has become the Royal National Institute for Blind People which” and here the text disappears behind an image. It should continue, “provided clothes for students at the Royal Normal College made from cloth that Thomson donated to them. The clothes, Armitage claimed, were warmer and three times more durable than in general.49 While all the other factories in the district were more than ordinarily depressed, Thomson’s factory was well-supplied with work. This was thanks in large part to the rejection of fashion in favour of tried-and-tested, high-quality goods, and dependable trade with the co-operatives.

I first started thinking about George Thomson seriously in 2017. I was in large part inspired to do so by my colleague and friend, Dr Mark Frost, of the University of Portsmouth. His book, The Lost Companions (2014), profoundly revised our scholarly understanding of the Guild of St George, its membership, and Ruskin’s treatment of them and his management of the organisation. Frost’s meticulous use of forgotten and neglected sources, and his re-examination of more familiar material, enabled him to recuperate the biographies of many of the working people who tried to make a practical reality of Ruskin’s theories and idealistic vision. In attempting to construct a fuller account of Thomson’s biography, I have been privileged to dedicate the result to Mark Frost, whose study invites scholars to pay more attention to hitherto shadowy figures like Thomson.

My pamphlet explores the basic facts of Thomson’s life. It asks what made Thomson tick, and how his understanding of Ruskin guided his innovative approach to business? For the first time it scrutinises Thomson’s business practices in detail. It provides answers to questions such as what was his philosophy, how did the industrial processes work at his mill, what was the nature of his relations with his workforce, who were his customers and how did they respond to the business and its products, and how successful was the experiment?

In 2017 I visited Huddersfield for the first time and found and photographed the places where the main Thomson family home once stood in Fartown, and where Woodhouse Mill was located in Deighton. I also went to Thomson’s final residence in Edgerton, the only building of the three which still stands. Appropriately, just north-east of Fartown—the district where Thomson was a representative on Huddersfield Council, and the location of his home, Woodhouse Hall—there is a residential street named Ruskin Grove. The photograph of the street-sgn understandably did not make it into the final edit of the pamphlet, but here it is, below. The mill stood due east of here, not far away, next to the Leeds Road and the Huddersfield Broad Canal, diagonally opposite Deighton Mill which, though re-purposed, still stands.

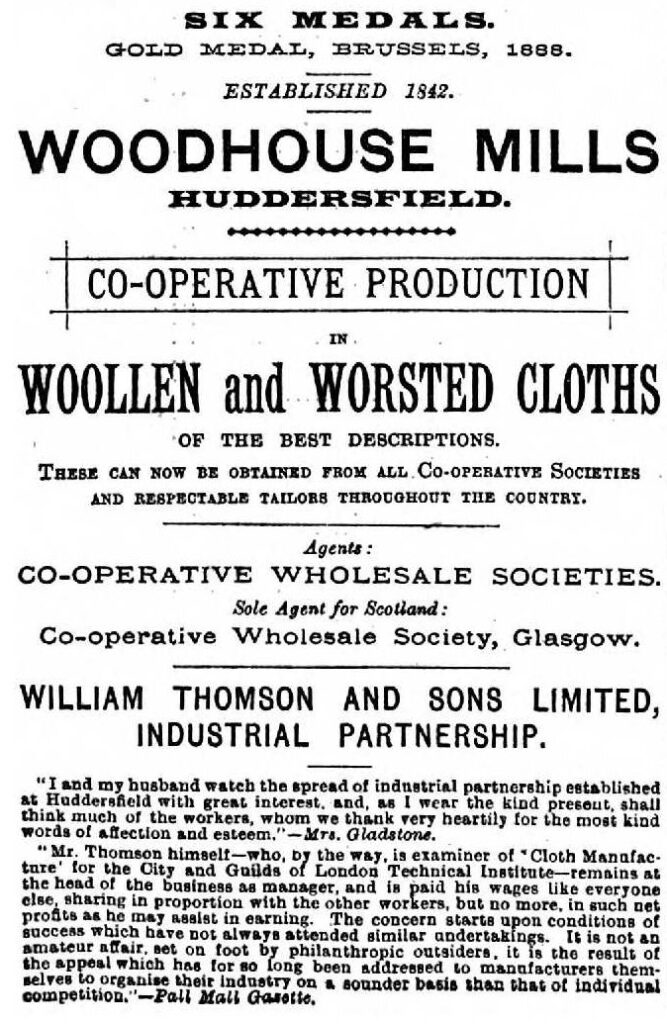

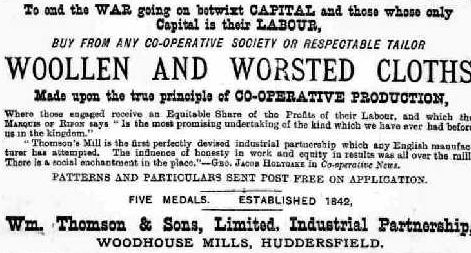

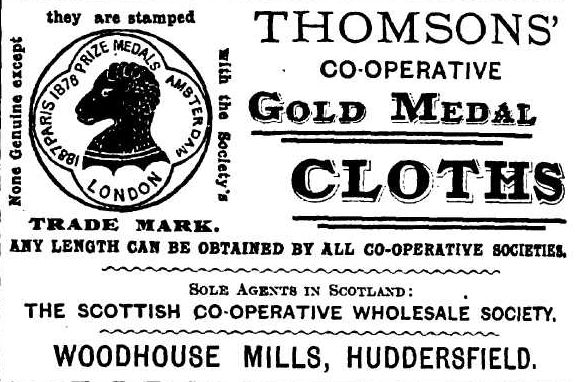

We did not find space in the pamphlet, either, for three newspaper advertisements, which I shall end by sharing. The first two appeared in 1888, while the last is from 1891 and show’s the company’s trademark. The testimonies and references to prizes speak to the success of the company and the pride it took in producing high-quality goods on fair terms both to the workforce and to customers.

I hope that my study of Thomson will be of interest to Ruskin scholars, students of historic industrial innovation and local historians in Huddersfield alike.

Please send any feedback to contact@stuarteagles.co.uk