Though renowned and sometimes mocked for his pronounced moral earnestness, John Ruskin nonetheless loved the theatre, pantomime, the zoo and—as we consider a more festive Ruskin—

THE CIRCUS

(for grown-up children everywhere).

“People mutht be amuthed, Thquire”, lisped Sleary, Dickens’s famous circus-master. Hard Times (1854) was a novel Ruskin admired because of its anti-utilitarian attack on Victorian political economy. Sleary’s Circus symbolizes the human empathy and imagination conspicuously lacking in the body politic. It is the opposite of the cold and remote rationality embodied in “the system”. Its authenticity is the antithesis of political hypocrisy and administrative incompetence. It is cheerfully, excitingly exotic rather than dismally commonplace. It promises escape from the fearful fetters of everyday burdens. It offers freedom and variety of expression instead of monotonously mechanical drudgery. It is honest. And that is why it appealed so readily to Ruskin.

What Ruskin liked above all was Dickens’s politics of fancy, rooted in the hearth and the heart. A politics of fancy that it was not fanciful to think realistic. Indeed, it promised an alternative reality, a more attractive reality—a better reality.

It was in a footnote to “The Roots of Honour”, the first of Ruskin’s hugely influential essays on political economy, Unto this Last (1862), that he voiced his appreciation of Dickens’s political “truth” in the same breath as he lamented its presentation in “a circle of stage fire”. (The paragraph is a long one, so I have split it in two to make it easier to read on screen.)

“The essential value and truth of Dickens’s writings have been unwisely lost sight of by many thoughtful persons, merely because he presents his truth with some colour of caricature. Unwisely, because Dickens’s caricature, though often gross, is never mistaken. Allowing for his manner of telling them, the things he tells us are always true. I wish that he could think it right to limit his brilliant exaggeration to works written only for public amusement; and when he takes up a subject of high national importance, such as that which he handled in Hard Times, that he would use severer and more accurate analysis. The usefulness of that work (to my mind, in several respects the greatest he has written) is with many persons seriously diminished because Mr Bounderby is a dramatic monster, instead of a characteristic example of a worldly master; and Stephen Blackpool a dramatic perfection, instead of a characteristic example of an honest workman. But let us not lose the use of Dickens’s wit and insight, because he chooses to speak in a circle of stage fire.

“He is entirely right in his main drift and purpose in every book he has written; and all of them, but especially Hard Times, should be studied with close and earnest care by persons interested in social questions. They will find much that is partial, and, because partial, apparently unjust; but if they examine all the evidence on the other side, which Dickens seems to overlook, it will appear, after all their trouble, that his view was the finally right one, grossly and sharply told.” (Ruskin 17.31n)

I wrote a 35,000-word MA dissertation on Ruskin and Dickens when I was a student at the University of Lancaster more than 20 years ago. I returned to the subject of circuses recently because of Ruskin’s friendship with a quite different Victorian figure, namely Oscar Wilde. I thought I had hit upon an amusing and potentially interesting shared experience. It turned out not to be what it seemed, but the story is worth recounting both for what we can learn about Ruskin’s attitude to circuses, and what it reveals about nineteenth-century show business and professional rivalry.

BUFFALO BILL

A poster for the 1912 film,

The Life of Buffalo Bill

Walter Crane recounts in his Artist’s Reminiscences that Oscar Wilde “pronounced a eulogy of ‘Buffalo Bill’” when the Colonel (William Cody) and his cowboys rode into town from America and made their first sensational appearance at London Earl’s Court in 1887. He continued:

“I believe it was Oscar Wilde who took us to visit the Colonel in his tent after one of the performances, greatly to the delight of our two boys, who examined his rifles and trophies with keen interest, and afterwards endeavoured to improvise a sort of ‘Wild West’ of their own in [the Cranes’] garden at Shepherd’s Bush.” (Crane 310)

Buffalo Bill toured the country and wowed audiences, and I thought for a moment that, like Oscar, Ruskin had seen him, too.

Soon after Ruskin, under severe mental strain, ran away from Brantwod to Folkestone in the summer of 1887, he visited the circus—not to join it at the merry age of 68, but to watch. He hoped it might calm his troubled mind and restore his spirits. If Ruskin read the local newspaper advertisements, he might reasonably have expected to see Buffalo Bill himself. On Friday, 12 August, the Folkestone Express promised that “all the old attractive features” of Sanger’s Circus could be expected, “and in addition a scene from Buffalo Bill’s show, ‘The stopping of a mail coach’’. But this was a triumph of publicity and was not the real deal.

Sanger’s Circus, otherwise called the Royal Olympia, was the domain of the British entertainer, “Lord” George Sanger (1825-1911).

Sanger provided a frank explanation of his “Buffalo Bill” ruse in chapter 38 of his memoirs, Seventy Years a Showman (1905). It is an amusing story, so I quote it here at length.

“[…] I am going to tell for the first time exactly in what circumstances I acquired the title of Lord George Sanger, by which I am so widely known. As I said in the beginning of my reminiscences I was not, as so many persons have fondly imagined, christened ‘Lord’, any more than I was born in Newbury Workhouse. But it did not suit me to contradict the various stories about the genesis of my title that were set floating, for the more people talked and wondered about me the better I was being advertised. Now you shall have the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.

“Well, then, I was first announced as ‘Lord’ George through the American invasion of our shores by the various big combination shows, more especially that of ‘Buffalo Bill’. For some time prior to his arrival in England the latter had been making a big hit in the States with his Wild West Exhibition of Indian, Cowboy, and Prairie life generally. In books of adventure over here the name of the Hon. William Cody had for some years figured very extensively. He was held up as the typical scout and Indian fighter, and the stories of his exploits, apocryphal and otherwise, as ‘Buffalo Bill’, were very popular.

“I was never behind the times with my show if I could help it, and having one or two real buffaloes, a number of unreal Red Indians, some good mules, and a rickety stage coach, I made ‘Scenes from Buffalo Bill’ one of the features of my circus and a standing line on the bill.

“I had been running this performance some twelve months before ‘Buffalo Bill’ and his ‘Wild West’ came to England, and when he did come, and his agents played the usual American ‘enterprising’ game of plastering over the bills of every rival show throughout the country, I determined, out of ‘sheer cussedness’, as my Yankee friends put it, not to drop the feature.

“Naturally, the Honourable William was annoyed with me, and at once sought the aid of the law to get ‘Buffalo Bill’ off Sanger’s bills. With their usual hustling methods, his agents rushed into the courts, and on an entirely ex-parte statement secured an injunction against me forbidding me to use the name of ‘Buffalo Bill’.

“My lawyers, Messrs. Lewis and Lewis, advised me, as there had been certain irregularities, to take no notice of the injunctions; so I went on as before, announcing and giving the ‘Buffalo Bill’ performance. The next move of the Americans was to try to get me committed to gaol for contempt of court, and I had to show up at the big building in the Strand to show cause why I should not be committed. There I met the Hon. William Cody. He went into the box, and I went into the box, and a very pretty display of contradictory statements resulted. After I had said what I had to say, I went off to Barnet, where my circus then was, to look after my business and await the result.

“That reached me just towards the close of the afternoon performance, in the shape of a telegram to say I had won the day. I read that telegram to the audience, who cheered me heartily, and I promised to put the facts before them in a special bill.

“As I was reading the evidence with a view to getting the bill ready, the continual reiteration of the phrase ‘The Honourable William Cody’ got on my nerves, and at last I said, ‘Hang it! I can go one better than that, anyhow. If he’s the Honourable William Cody, then I’m Lord George Sanger from this [time] out!’ […] From an advertising point of view it was one of the best things I ever did […]”

The legal battles were a little more complicated than Sanger suggests, but that is not important here, and he goes on to declare:

“As regards myself and American showmen, I should like to say that outside business rivalries we have always been the best of friends, and my name is as well known in America as it is on this side of the water.”

It is not clear that Buffalo Bill felt quite the same, and Sanger could not resist adding, “[…] I must insist upon the fact that England has nothing to learn from America, at least as regards the show business”, a characteristically bold claim.

RUSKIN AND THE CIRUS

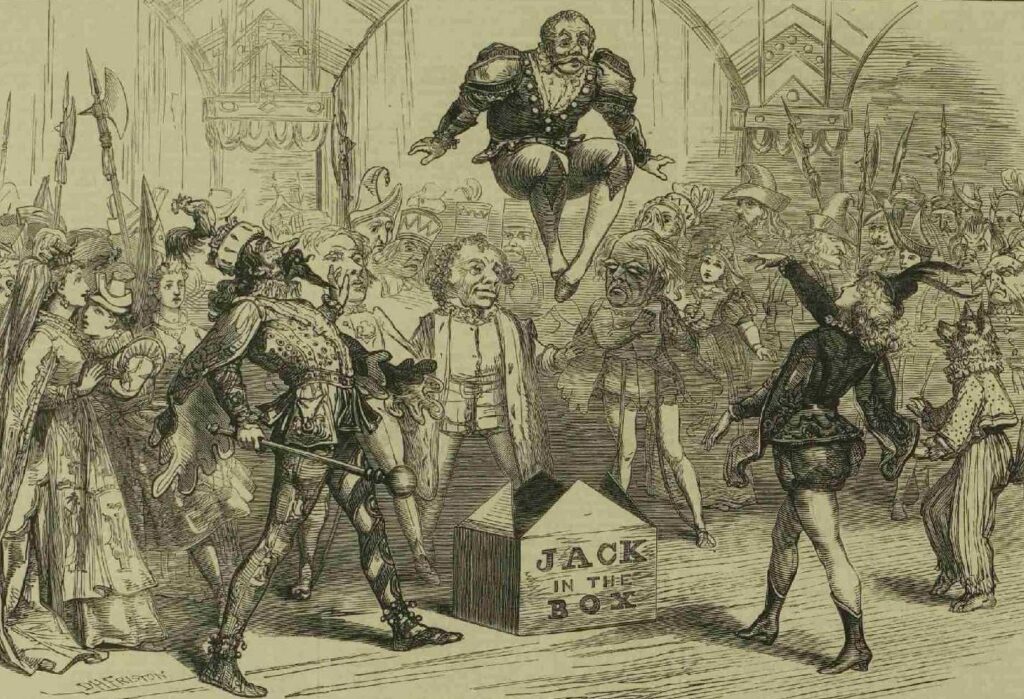

“Christmas Pantomime”: a scene from Jack in the Box

at Drury Lane Theatre, published in the

Illustrated London News (10 January 1874)

As so often, we owe it to E. T. Cook that we can say anything about what Ruskin thought of Sanger’s Circus with its fraudulent scene from “Buffalo Bill”. In his biography of Cook, J. Saxon Mills quotes from entries Cook wrote in his diary after meeting with Ruskin at Morley’s Hotel on Trafalgar Square late in 1887. Ruskin told him:

“there wasn’t half enough clown. And the elephants were shown off too much: the real charm in an elephant is to watch his native sagacity. And the chariot race was terrible—the vulgarization of the noblest thing, I suppose, in Greece.” (Saxon Mills 79)

The closing comment would seem to be Ruskin’s verdict on the fake Buffalo Bill scene about the getaway mail coach.

It is in Letter 39 of Fors Clavigera, in an installment written for March 1874, that Ruskin has most to say about the true function of circuses. His main reference is to Hengler’s Circus which was established in 1847. He begins his letter by explaining that

“On a foggy forenoon, two or three days ago, I wanted to make my way quickly from Hengler’s Circus to Drury Lane Theatre, without losing time which might be philosophically employed; and therefore afoot, for in a cab I never can think of anything but how the driver is to get past whatever is in front of him.” (Ruskin 28.48)

He later relates how he was “just in time to get my tickets for Jack in the Box, on the day I wanted, and put them carefully in the envelope with those I had been just securing at Hengler’s for my fifth visit to Cinderella” (Ruskin 28.50)

As he wended his way through the streets to go from one production to the other, he asked himself, “Which is the reality, and which the pantomime?”

“Nay, it appears to me not of much moment which we choose to call Reality. Both are equally real; and the only question is whether the cheerful state of things which the spectators, especially the youngest and wisest, entirely applaud and approve at Hengler’s and Drury Lane, must necessarily be interrupted always by the woeful interlude of the outside world.” (Ruskin 28.51)

The fact that the circus, the theatre, and the pantomime represent some sort of escape from the outside world, if not quite a sanctuary, necessarily invests such entertainments with political significance, as in Dickens made masterfully clear in Hard Times. Ruskin, though, adds a religious dimension, writing at a time when his Christian faith was broadening under the strain of many personal burdens (most obviously his tortured love for Rose La Touche). He goes so far as to liken the church to a place of entertainment. His satire is biting: he wants us simultaneously to laugh and to nod in recognition and agreement. It is perhaps the strongest case Ruskin ever made for the Politics of Fancy. Fairy-tale worlds are more real than the everyday. They are, indeed, closer to what the so-called “Real World” should be. I quote Ruskin at length (and as usual I have split the paragraph for ease of reading on screen).

“It is a bitter question to me, for I am myself now, hopelessly, a man of the world!—of that woeful outside one, I mean. It is now Sunday; half-past eleven in the morning. Everybody about me is gone to church except the kind cook, who is straining a point of conscience to provide me with dinner. Everybody else is gone to church, to ask to be made angels of, and profess that they despise the world and the flesh, which I find myself always living in (rather, perhaps, living, or endeavouring to live, in too little of the last). And I am left alone with the cat, in the world of sin.

“But I scarcely feel less an outcast when I come out of the Circus, on week days, into my own world of sorrow. Inside the Circus, there have been wonderful Mr Edward Cooke, and pretty Mademoiselle Aguzzi, and the three brothers Leonard, like the three brothers in a German story, and grave little Sandy, and bright and graceful Miss [Jenny] Hengler [renowned as an equestrian], all doing the most splendid feats of strength, and patience, and skill. There have been dear little Cinderella and her Prince, and all the pretty children beautifully dressed, taught thoroughly how to behave, and how to dance, and how to sit still, and giving everybody delight that looks at them; whereas, the instant I come outside the door, I find all the children about the streets ill-dressed, and ill-taught, and ill-behaved, and nobody cares to look at them. And then, at Drury Lane, there’s just everything I want people to have always, got for them, for a little while; and they seem to enjoy them just as I should expect they would. Mushroom Common, with its lovely mushrooms, white and grey, so finely set off by the incognita fairy’s scarlet cloak; the golden land of plenty with furrow and sheath; Buttercup Green, with its flock of mechanical sheep, which the whole audience claps because they are of pasteboard, as they do the sheep in Little Red Riding Hood because they are alive; but in either case, must have them on the stage in order to be pleased with them, and never clap when they see the creatures in a field outside. They can’t have enough, any more than I can, of the loving duet between Tom Tucker and little Bo Peep: they would make the dark fairy dance all night long in her amber light if they could; and yet contentedly return to what they call a necessary state of things outside, where their corn is reaped by machinery, and the only duets are between steam whistles.

“Why haven’t they a steam whistle to whistle to them on the stage, instead of Miss Violet Cameron? Why haven’t they a steam Jack in the Box to jump for them, instead of Mr Evans? or a steam doll to dance for them, instead of Miss Kate Vaughan? They still seem to have human ears and eyes, in the Theatre; to know there, for an hour or two, that golden light, and song, and human skill and grace, are better than smoke-blackness, and shrieks of iron and fire, and monstrous powers of constrained elements. And then they return to their underground railroad, and say, ‘This, behold,—this is the right way to move, and live in a real world.’

“Very notable it is also that just as in these two theatrical entertainments—the Church and the Circus,—the imaginative congregations still retain some true notions of the value of human and beautiful things, and don’t have steam-preachers nor steam-dancers,—so also they retain some just notion of the truth, in moral things: Little Cinderella, for instance, at Hengler’s, never thinks of offering her poor fairy Godmother a ticket from the Mendicity Society. She immediately goes and fetches her some dinner. And she makes herself generally useful, and sweeps the doorstep, and dusts the door;—and none of the audience think any the worse of her on that account. They think the worse of her proud sisters who make her do it.

“But when they leave the Circus, they never think for a moment of making themselves useful, like Cinderella. They forthwith play the proud sisters as much as they can; and try to make anybody else, who will, sweep their doorsteps. Also, at Hengler’s, nobody advises Cinderella to write novels, instead of doing her washing, by way of bettering herself. The audience, gentle and simple, feel that the only chance she has of pleasing her Godmother, or marrying a prince, is in remaining patiently at her tub, as long as the Fates will have it so, heavy though it be. Again, in all dramatic representation of Little Red Riding Hood, everybody disapproves of the carnivorous propensities of the Wolf. They clearly distinguish there—as clearly as the Fourteenth Psalm, itself—between the class of animal which eats, and the class of animal which is eaten. But once outside the theatre, they declare the whole human race to be universally carnivorous—and are ready themselves to eat up any quantity of Red Riding Hoods, body and soul, if they can make money by them.

“And lastly,—at Hengler’s and Drury Lane, see how the whole of the pleasure of life depends on the existence of Princes, Princesses, and Fairies. One never hears of a Republican pantomime; one never thinks Cinderella would be a bit better off if there were no princes. The audience understand that though it is not every good little house-maid who can marry a prince, the world would not be the least pleasanter, for the rest, if there were no princes to marry.” (Ruskin 28.51-53)

KENNETH GRAHAME

Let’s end by returning to Lord George Sanger whose memoirs were eventually reissued with an introduction specially written by Kenneth Grahame, fondly remembered now as the author of The Wind of the Willows (1908). Looking back at the pre-cinema heyday of the circus, Grahame concluded his comments with this powerful evocation of England’s green and pleasant past. Grahame admired Ruskin, and it is difficult to imagine that the Ruskin who wrote so powerfully of Hengler’s and so eloquently of English rural life could disagree with Grahame’s judgement. We can confidently add Ruskin into the tapestry Grahame weaves with threads from Sanger, Shakespeare and Dickens. (Again, I’ve split this into shorter paragraphs for the convenience of reading it on screen.)

“Well, if our circus-revels now are ended, which I devoutly hope is not really the case, at least their record will remain, writ by their own Prospero. For a magician George Sanger really was, sending out his Ariels along all the roads of the world, and with masques and solemn processions entertaining kings and queens—yea, ever her who gives its title to that bygone period, Queen Victoria herself.

“Therefore some will prefer the later chapters of this simple but high-spirited book, records of triumph upon triumph in this strange world of barbaric display and trumpeting processions wherein he moved like an emperor.

“For myself I like best the early struggles, the simple joys and sorrows, the wanderings of little George and his indomitable father upon the open road with its ale-houses and toll-gates, over commons, or with their pitch on a wayside strip of grass, with their peep-show and its accompanying patter. And I like to think that in one of their little roadside audiences might have been seen, lingering and listening and noting, a handsome young man, a bit of a dandy in his dress, already known to his friends as a lad of some promise—one Charles Dickens.”

SOURCES

Walter Crane, An Artist’s Reminiscences (London: Methuen & Co., 1907)

John Ruskin, The Works of John Ruskin, ed. E. T. Cook & Alexander Wedderburn (39 vols) (London: George Allen, 1903-12)

- Saxon Mills, Sir Edward Cook KBE: A Biography (London: Constable & Co., 1921)

Lord George Sanger, Seventy Years a Showman (with an introduction by Kenneth Grahame) (London: E. P. Dutton,1926) (originally published 1905)

Please send feedback to contact@stuarteagles.co.uk