Last time, we looked at William White’s family background and early career. Now our focus turns on his period as curator of the Ruskin Museum. It’s time to re-examine White’s achievements and limitations and to reassess his contribution both to Ruskin’s legacy and Sheffield’s heritage.

-

WILLIAM WHITE, CURATOR OF THE RUSKIN MUSEUM:

(II) A NEW LIFE IN MEERSBROOKStuart Eagles

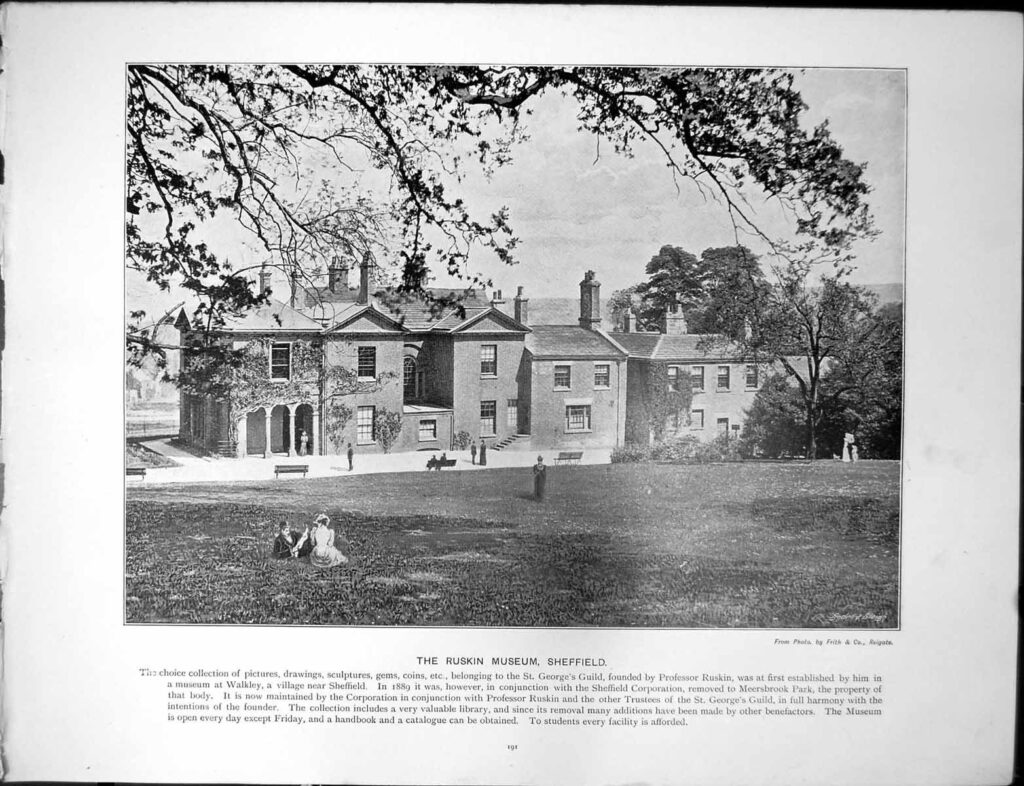

William White believed, with some justification, that he understood Ruskin’s purpose in setting up the museum far more thoroughly than the committee tasked with its management—i.e. the Ruskin Museum Committee (hereafter, the RMC). But what White neglected properly to admit was the RMC’s authority, specifically its authority over him. Meersbrook Hall and the park in which it was situated were owned by Sheffield Corporation, and maintained by the local council which also paid the wages of a caretaker, gardeners, museum attendants and, of course, the curator. The Ruskin Museum, moreover, was part of Sheffield’s broader cultural offer of museums, libraries, parks and recreation facilities. The contents of the museum, however, were owned in trust by Ruskin’s Guild of St George, and Sheffield Corporation had possession of them on loan for a period of 20 years. The RMC was therefore composed of local councillors (most of whom were also businessmen) and Guild trustees. As it happens, the Guild’s trustees—George Baker and George Thomson—were also businessmen and leading councillors where they lived. Any curator of the Ruskin Museum would have to satisfy both Sheffield Council and the Guild.

Another factor was the Museums Association. It was founded in part to harmonize and standardize best practice within and between towns and cities across different regions and throughout the country. Its roots were planted firmly in Sheffield. Elijah Howarth (1853-1938), the curator of Sheffield’s Weston Park Museum, had proposed the formation of a Museums Association in 1877, and it was eventually founded ten years later. Howarth would play a major role on its committee, and was the long-term editor of its journal. Inevitably, White, as curator of the Ruskin Museum, was a significant member of the organization. The Association’s first meeting took place in Liverpool in 1890. White attended with a key member of the RMC, Ald. William Henry Brittain (1835-1922), who would serve as a councillor in Sheffield for 50 years. Brittain was elected the Association’s President. By 1900, Brittain was the Association’s Treasurer. Howarth was its Secretary from 1891 to 1909.

Given this background, it is hardly surprising that the Ruskin Museum, which had far more space than the cottage at Walkley, would adopt a more orthodox, standard curatorial approach. Ruskin scholars have justifiably criticized as “unRuskinian” the practice of separating out items by type, style and date and displaying them discreetly—with a Picture Gallery distinct from the Minerals Room, the Library etc. It was “unRuskinian” because it disrupted and otherwise obscured the connections between objects which were such a crucial part of Ruskin’s educational purpose. Ruskin wanted people not merely to admire the striking colours of minerals, for example, but to appreciate how these colours connected in significant ways with particular paintings—sometimes in a practical sense (literally providing the artist with the desired colour of paint), often by means of symbolism (a precious stone being invested with meaning by an artist’s representation of it), and every meaningful connection invested with moral value. It was part of Ruskin’s endeavour to teach people about the connectedness of things in a world built on mutual interdependence, and it was a lesson he meant visitors to the museum to learn by viewing objects side-by-side.

William White certainly had a share in the responsibility for this curatorial change, but so did Sheffield Council and the Guild as represented in the RMC, and so did the Museums Association, which was institutionally less sympathetic to Ruskin’s highly idiosyncratic approach. Moreover, having more space in and of itself encouraged classification and organization that tended to separate rather than combine for the sake of simplification. What worked well at Walkley did so because it was on a smaller scale and the curators could always be on hand. A larger local authority museum in a public park could not reasonably operate on the same basis.

It is also the case that White demonstrated, in the papers he gave to the Museums Association, some of which were published in the Association’s Proceedings, that he thoroughly understood Ruskin’s purpose and intended approach. At Glasgow in 1896, for instance, he addressed the MA on “Museum Libraries”, while at the Sheffield meeting in 1898, he spoke on “The Individuality of Museums” and provided for the Association’s published transactions, “Practical Notes, and Suggestions on Modes of Exhibiting Museum Specimens”. Most significantly, in 1893 White gave a paper on “The Function of Museums as considered by Mr Ruskin” to the Association’s conference held at the Zoological Society at Hanover Square in London. The account of the talk given in the Manchester Guardian reveals the extent to which White tried, in his curatorial practice, to honour Ruskin’s ideals and intentions, but it also reveals an attitude that would cause a widening gulf between him and the local community in Sheffield:

“[…] the museum was primarily regarded by Mr Ruskin not as a place of entertainment but as a place of education, not as a place for elementary education but for that of far advanced scholars; it was by no means the same thing as a Sunday school or day school, or even as the Brighton Aquarium. —(Laughter.) “A museum directed to the purpose of ethics as well as scientific education must,” Ruskin wrote, “contain no vicious, barbarous, or blundering art, nor abortive or diseased types of natural things.” Personally Mr White thought that one of the greatest mistakes at present allowed in museums was the unlimited range of the exhibits. Each museum before attempting anything else should be distinctively local in its character. The ordinary attempt to be universal was as futile as it was bewildering. Mentioning that Mr Ruskin was opposed to the opening of museums on Sunday, Mr White said his experience of the opening of the Ruskin Museum on that day was that the visitors then were not of the nature of students, and whatever beneficial advantage they derived was of an accidental kind—was neither sought nor followed up in any way.” (Manchester Guardian, 5 July 1893)

White’s assertion about Ruskin’s negative opinion of opening the museum on Sundays is wrong—Ruskin did not object to Walkley opening its doors on Sunday (see Ruskin, Works, 28.747-748). More importantly, in what White says, there is a troubling contradiction between a Ruskinian sensitivity to local character in the selection and display of objects, and a dismissive attitude to the general public that reveals White’s disdain for casual visitors—for the sort of local resident of Sheffield who might drop by the museum on a stroll through the park. This showed a cavalier disregard for the nature of the local authority museum of which he was curator. His bold admission of snobbery in such a forum as the Museums Association demonstrates a tactlessness and lack of diplomacy that would prove to be his undoing. He was not the sort of man who could successfully walk the tightrope between the Guild’s Ruskinian ideals and Sheffield Council’s grittier practical concerns. Resentment built over a long period on both sides. But that is not to suggest that White’s curatorship was devoid of value or achievement. On the contrary, his legacy is considerable and enduring.

William White, pictured (standing) at the Museums Association meeting in Dublin in 1894.

WHITE AND THE GUILD COLLECTION

“I take the liberty of writing to you knowing the interest you took from the first in Mr Ruskin’s beneficent concerns”, White told Mrs Fanny Talbot in a letter in November 1892. The donor to the Guild of fishermen’s cottages in Barmouth, Wales, and of treasures for the Ruskin Collection, Guild Companion Mrs Talbot had evidently visited the museum at Meersbrook at a time when the curator was absent. White went on:

“The success and ever increasing interest of the museum is most satisfactory and encouraging, and I have several times thought that before long the activity of the Guild might be revived with very great success, now the museum is so thoroughly well established.”

But there was a snag. The Guild’s funds were very limited, and had Sheffield Corporation not paid for the new glass roof at Meersbrook Hall, White said, “I do not know what would have happened”. He continued, “My endeavour is to make the Museum what Mr Ruskin intended it to be—& even more, for it is to be a perpetual monument to him!!” (White’s emphasis.)

Asking Mrs Talbot if she might contribute to the purchase of a picture by Angelo Alessandri (1854-1931) he told her, “I do not at all mind begging for Mr Ruskin”, such was the scale of his ambition for the museum. “While in Venice I saw Sig. Alessandri (who makes more lovely copies of Carpaccio, Tintoretto &c than ever, + cannot speak too highly and lovingly of (his dear master) […]” White told her. White had seen him

“at work upon a study of St Ursula’s head. As it was not a decided commission I took the responsibility of asking him to send it here when finished, in the hopes of our having it for the Museum; and promised to sell it for him if we were unable to keep it (!). It has now come & such a charming thing that it would delight Mr Ruskin (if possible, alas) could he but see it. The cost is only some 12 or 15 pounds, but as I know the funds have run out just now, & there are a few outstanding accounts, I hardly like to write to ask Mr Baker at present if he can decide to buy it. Will you please help us?” (White’s emphasis.)

Ruskin was incapacitated by poor health and old age from any involvement in the Guild’s affairs. White was clearly determined to add to the collection in Ruskin’s spirit, championing subjects and artists that were obviously in scope. White also commissioned from Alessandri a large watercolour copy (13ft 6in by 2ft), of Carpaccio’s The Presentation of Christ in the Temple (displayed in the Accademia in Venice) and this was certainly added to the collection late in 1896.

The Guild trustees also purchased Alessandri’s watercolour copy of “The Stoning of St Stephen” after Tintoretto at San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice (in 1894) and three other watercolour studies by Alessandri of Tintorettto’s paintings in the Scuola di San Rocco, including “The Flight into Egypt”, “The Annunciation” and “St Mary of Egypt” (in 1896).

White boasted to Mrs Talbot about his devotion to the museum and his allegiance to Ruskin’s ideals, whilst appealing for funds in a manner both shameless and ultimately unsuccessful. As he did so, he underlined that snobbish disdain for local people that we have already identified as one of the main causes of his ultimate downfall: “[…] though I feel very grateful for the measure of success that the work is meeting with”, he wrote

“I cannot but feel that it is a shame that more cannot be done. The Sheffield people are, almost to a man, entirely wrapped up in their business pursuits, & incapable of understanding the aims & purposes of Mr Ruskin as they read nothing beyond the newspapers,—although, at the same time, they are very proud of the museum, & not once has a single item of expenditure been questioned in the Council.”

Notwithstanding this caveat, White’s disappointment in the people of Sheffield is palpable. Moreover, he would never convince the majority of Guild Companions to join him in his endeavours to raise money and buy more items. And, according to the collection’s first historian, Catherine Morley, Ruskin himself “disapproved of [White]” (Catherine W. Morley, John Ruskin, Late Work, 1870-1890: The Museum and Guild of St George, An Educational Experiment (London & New York: Garland, 1984) p. 227). Feeling increasingly alone and embittered, White’s dissatisfaction grew, and so did Sheffield Council’s. Eventually the council felt obliged to act.

Yet, notwithstanding, it would be unfair to convict White of being “unRuskinian”. He had deep knowledge of Ruskin’s ideas and values, and to a great extent seemed to approve of and share in them. He was sincerely dedicated to the aims of the museum. And he worked hard to add sensitively to the collection.

Writing about “The Ruskin Museum and its Treasures” in the Windsor Magazine in 1895, Alfred Sprigg commented:

“As one who has spent many pleasant mornings [at the Ruskin Museum], I make bold to affirm that only the veriest Philistine could examine these treasures and gossip about them with Mr William White, the curator, who is au fait on everything connected with Mr Ruskin and with the works of J. M. W. Turner, and not rejoice in his visit, and praise the skill and judgment of those responsible for the collection” (p. 134).

In the same year, the Sheffield Evening Telegraph referred to White as “the esteemed curator of the beautiful little museum at Meersbrook” (18 November 1895).

WHITE AND THE RUSKIN MUSEUM

One of the ways in which White promoted appreciation of the collection was through talks he gave at the museum. Although no account of them appears to have survived, the Ruskin Museum Committee noted in its minute book that they granted permission for the Library to be used one evening a week during the winter for the purpose of delivering lectures on art (7 December 1893).

White seems to have worked hard to promote the museum outside Sheffield. Though laudable in itself, this was problematic in several respects. For one thing, when he was absent from Sheffield, the museum usually had to close. It was symptomatic of his neglect of local relationships. He seems to have courted studious audiences farther afield, and disdained the casual, local visitor.

In March 1891, White visited the London Institution in Finsbury Circus to deliver to the local Ruskin Society “an interesting paper” on the objects of the Guild and the origin of the museum (Sheffield Independent, 16 March 1891). In March 1896, he addressed the Ruskin Society of Glasgow on “The Treasury of St George”. The Sheffield Daily Telegraph noted, “The society proposed paying a visit to the museum before long. Some of the members have already been here once or twice” (6 March 1896).

Another way in which White and the RMC reached out to a wider public was through the granting of loans from the collection. Guild trustee George Thomson borrowed certain unspecified pictures for exhibition in Huddersfield in October 1891. Shortly afterwards, his fellow Guild trustee, George Baker, successfully requested the loan of “certain casts” for the Birmingham School of Art (12 November 1891). Eight casts were also loaned to the Sheffield School of Art for use in the Central School’s Modelling Room (7 April 1892).

In December 1893, the RMC agreed to make a loan of pictures to the Liverpool Ruskin Society (2 December 1893). In March 1899, Thomson secured a loan of drawings to Huddersfield Corporation for exhibition at the town’s Fine Art Gallery (2 March 1899). The committee minutes contain no details of this loan, but it was reported in the local press that it consisted of 30 watercolour drawings: “The sketches in the room set apart for the collection from the Ruskin Museum are of considerable interest for coming from students of Ruskin, notably T. M. Rooke, who is very strongly represented, and of whose work, generally, the eminent painter spoke very highly” (Huddersfield Daily Chronicle, 17 March 1899). Thomson had also previously secured loans for the annual exhibition of the Huddersfield Art Society of which he was President for many years (Huddersfield Daily Chronicle, 5 January 1896).

White’s absences to give lectures, attend conferences, deliver loan items and undertake research trips were mitigated to some extent by the appointment of an assistant. This was a significant development, yet the name of Miss (Ann) Elizabeth Carr, the first person to be appointed to the position, has curiously escaped the notice of all scholars to have studied the history of the museum. This may be in part a result of very limited information being available about her (and I have been unable to identify her in any records besides the minute books of the Ruskin Museum Committee). Miss Carr was appointed on 9 April 1891, less than a year after the museum opened, on a salary of £30 per annum, paid monthly (30 April 1891). This was increased to £35 per annum on 8 June 1893 on condition that her duties were expanded to include assistance with conducting visitors around the museum. She resigned in the summer of 1898 (4 August 1898). The fact that she worked so closely with White at the museum for more than seven years is indicative of at least a tolerable working relationship.

Miss Carr’s successor, (Constance) Genivieve Pilley (1878-1958) served the Ruskin Museum in a curatorial capacity for more than 50 years. In August 1898 the RMC advertised for a ‘Lady Assistant’ to be paid a salary of £30pa. Genevieve was appointed by the committee’s chairman, Joseph Gamble, his deputy, W. H. Brittain and G. J. Smith. She started work on 12 September, and under the terms of her contract she could quit with one month’s notice. Although White had left his role as curator within a year, there is no evidence that he and Miss Pilley did not get along.

It appears that many visitors to Meersbrook Hall—certainly those who had travelled some distance to get there, or had booked an appointment—were conducted around the museum personally by White or his assistant, a custom continued from the Swans’ time at Walkley.

VISITORS TO THE MUSEUM

On 28 April 1890, less than two weeks after the opening of the museum, White wrote that the visitors were “multifarious”: “numerous beyond all expectation, so that at times the rooms are inconveniently crowded”. Between 600 and 700 people visited each day, he reported, and “on Saturdays and Mondays, when [the Museum is] kept open until nine o’ clock, more than double that number has attended; while on the two Sunday afternoons, during only three hours of opening, at least three times this number have passed through the door on each occasion” (Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 30 April 1890). Towards the end of 1890, the RMC recorded the daily averages for the first 26 weeks of the museum’s operation. They ranged from a low of 5,405 on Wednesdays and a weekday high of 12,267 on Mondays (when it was open until late), to 14,103 on Sunday afternoons; from least to most popular day, the order ran Wednesday, Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday (when most men still did paid work, at least in the morning), Monday and Sunday afternoon (4 December 1890). Annual visitor numbers remained around 60,000 until the mid-1890s, but this declined by about a quarter towards the end of the decade.

Students were not admitted to the library at the museum until 12 November 1890, by which time White had completed “the preparation of a catalogue and the classification of the content” (Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 12 November 1890). It was made very clear to visitors that the library was intended “not [for …] the multitude, but as a resort [sic] for the student bent upon serious inquiry and legitimate work” (ibid.). That notion of “legitimate work” is apt to trouble us today. Though broadly sympathetic to these firm regulations, the Sheffield Daily Telegraph hinted at possible discontent when it referred to them as “somewhat stringent conditions” which it spelled out in detail. The rules will not, however, strike any modern researcher, familiar with archival practices today, as in any way out of the ordinary.

“Visitors will be required to fill up a form stating the volumes or engravings they wish to inspect and appending their names and addresses. They will be granted the use of only one volume at a time, and will be required to use every care with it, and to abstain from touching the surface of any print or drawings. No writing fluid of any kind will be permitted in the room, and where permission is granted to make a tracing it can only be done under the supervision of the curator. In addition to this it is laid down in the rules that a comparison of prints and drawings, not the property of the Guild, can only be made under his superintendence.”

Such restrictions were deemed necessary by the council as well as by White because of the trouble experience at Weston Park Museum from “Roughs”, especially during public holidays.

A sense of how White was viewed by the more studious visitors to the museum can be gauged from an account in the Transactions of the Leeds Naturalists’ Club and Scientific Association (Leeds (1890) p. 54). The club’s members visited Meersbrook on Saturday, 21 June 1890. Their report recorded that a “very pleasant and profitable afternoon” was led by the “very courteous and able curator” William White, who “explained in detail many of the interesting objects in the Museum”. The party began its tour in the room which contained “the casts and minerals, and these were interpreted by Mr [Henry] Hewetson [of the Naturalists’ Club] and Mr White”. The group then proceeded to the Picture Gallery, and ended their visit in the Library. The report describes the collection in some detail and demonstrates the extent to which White warmly engaged with his fellow amateur scientists. They were serious students, not casual local visitors. Indeed, some members of the party achieved eminence, such as the botanist and mycologist, Harold Wager (1862-1929) who, in 1904, became a Fellow of the Royal Society.

Among other famous visitors to the museum during White’s time was the Scottish writer, poet, suffragist and reformer, Isabella Fyvie Mayo (1843-1914), who described the museum sympathetically in an essay on “Sheffield, yesterday and today” in her collection, The Sunday at Home (1898-99), which included the sketch below.

According to entries in the last of the visitor books, which had been started at Walkley, the museum at Meersbrook was visited on 9 July 1890 by someone from Zanzibar in East Africa. On Monday, 10 November 1890, 33-year-old Henriette Emily Colenso (1847-1932), visited from Bishopstowe, Natal (modern-day South Africa). She was the eldest daughter of John William Colenso (1814-1883), the mathematician, theologian, Biblical scholar, social activist, the first Church of England Bishop of Natal, and a champion of Zulu rights and interests. Ruskin was a vocal supporter of his. Henriette followed her father in advocating for Zulu rights, strongly resisting British imperial policies. The context for her visit to the museum at Meersbrook was that on 7 November she had made a public address at the Unitarian Channing Hall on the subject of the Zulus, entitled “English Deeds in Natal” (Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 8 November 1890). On Sunday the 9th, she addressed the Upperthorpe Unitarian Chapel on the same subject, though “Zululand” was substituted for “Natal” in the title (ibid., 11 November 1890).

(It is worth noting that Henriette went to school at Winnington Hall in the 1860s when her father took refuge there, and Ruskin occasionally gave classes. Henriette’s sister, Frances (or Fanny) Colenso (1849-1887), also staunchly supported her father and became a historian of the Zulu wars. She stayed with Ruskin at Brantwood in 1880 and became a Companion of the Guild of St George.)

WHITE’S PUBLICATIONS

One of the ways in which White sought to aid comprehension of Ruskin’s collection was through the compilation of three published catalogues and guides. It was also a means of alerting a wider public to the existence and importance of the museum. Together, they constitute White’s greatest legacy, providing valuable information and insight for future generations as well as contemporary visitors. All of them were published by George Allen. That is not to suggest that all his assertions are convincing, or that his work was free from error, but their value is enduring. They reveal the impressive extent of his knowledge and the thoroughness of his studies, his skill as a writer, and his undoubted dedication to the work. They also confirm his orthodox approach to curatorial practice and his clarity and decisiveness of classification (but this was achieved somewhat to the detriment of highlighting meaningful Ruskinian connections).

The first title to be published was A Descriptive Catalogue of the Library and Print Room of the Ruskin Museum , an indexed 95-page booklet published by George Allen which was prepared by White as he rearranged the museum’s library.

William White, A Descriptive “Catalogue of the Library and Print Room of the Ruskin Museum” (London: George Allen, 1890).

“In the arrangement of the books, prints, and manuscripts, an excellent scheme has been followed, and one which has the sanction of Mr Ruskin himself”, claimed the Sheffield Daily Telegraph, somewhat dubiously. Their summary is nonetheless a useful one which also serves as a reminder of how newspaper book reviews could promote a subject far beyond the immediate readership of the publication under scrutiny.

“Unfortunately, the state of the master’s health has not permitted him to describe the treasures of the Museum in his own matchless style, as he once hoped to do; but in this compilation of the first section—the library section—of the catalogue Mr White has given the world a concise, interesting, and satisfactory guide. In a prefatory note he says that he has endeavoured to present it in a form such as Mr Ruskin might approve ‘using available means of embellishing it, both by minute study of the works themselves in connection with their individual history, and by research in relation to his writings respecting them’. The library is divided into seven sections. First there are the manuscripts, black letter and medieval books, including many beautifully illuminated missals and choice bindings. Next comes the works of travel, embracing early voyages of discovery and ancient atlases; and then there is the third section, which is exclusively occupied with natural history. The magnificent collection of illustrations of birds, fishes, and insects is probably unique, and practically priceless. In the division devoted to fine arts, there is a rich store of works relating to the arts of ancient Greece and Rome, the plastic arts, and metal work; and a most valuable and interesting array of drawings and engravings illustrative of the Italian, German, and English masters, both ancient and modern. The fifth section is filled with classical literature—Grecian, French, and English—the English works being classified into the 14th, 16th, 18th, and 19th centuries, and including all the best works of Mr Ruskin. British history has a division to itself, where may be found the historical records of every regiment in Her Majesty’s service; and the seventh section is a haven for books which come under the head of general literature. The majority of these works, as Mr White explains, have been selected by Mr Ruskin and given to St George’s Guild as creations of genius, as specially worthy of study, and as coming within the scope of the master’s system of culture. It may be of some interest to the general readers to know that the English authors who stand highest in his estimation are F. Bacon, Alex. Pope, Dr Johnson, Sir Walter Scott, and Thomas Carlyle. The curator has not been able as yet to epitomise the Eyton collection of more than six thousand beautiful pictures of birds, from all parts of the world, including three hundred drawings which have never been engraved, but he promises to compile a complete index of at no distant date. Sufficient has been written here to show that the Ruskin Library is a small and select one, designed according to a well-defined plan, and that as it contains many rare works of great value it can only be used under somewhat stringent conditions.” (Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 12 Nov 1890)

A Popular Handbook to the Ruskin Museum, Sheffield came next—a pamphlet of 23 pages sold for tuppence. It was commissioned by the RMC on 6 August 1891. White was supervised in its preparation by committee member, Councillor Robert Eadon Leader (1839-1922), the owner and editor of the Liberal Sheffield Independent. White appears to have completed it inside a month. The bulk of it was ready to be printed on 3 September, though White’s introductory remarks are dated October. White starts with a brief description of the mineral collection (pp. 1-4), proceeds with the architectural casts (pp. 4-6), but concentrates on the Picture Gallery (pp. 6-14). After summarizing pictures of buildings, arranged by place, he turns to the early Italian masters, arranging them in order of birth from the oldest to the most recent. He then turns to works by Ruskin, then works by and copies of Turner, drawings of natural history objects, and drawings by John Leech and Francesca Alexander. Finally, he gives a brief description of the library and print department (pp. 14-17), turning from manuscripts to geographical and travel works, works of literature to British military history and, lastly, natural history, including the magnificent and extensive images of birds in the Eyton Collection. A note on coins, medals and seals precedes a summary of the museum’s print collection. It is little more than a list, and great portions of the collection are merely gestured at, such as the Eyton Collection, but White quotes from Ruskin’s works throughout, always keen to highlight why Ruskin thought an object, artist, subject or treatment was exemplary of its type. But, once again, what he gains in clarity of classification loses the vital sense of Ruskinian connectedness.

What turned out to be White’s final publication for the museum, however, was serious and substantial. In the summer of 1892, while the Ruskin Museum was undergoing structural alterations, including the installation of a glass roof, levelled floors and re-plastered ceilings, White travelled to Europe on a Ruskinian research trip. As he explained to Fanny Talbot:

“[…] I went to Italy covering almost the entire ground in Italy frequented by Mr Ruskin, on behalf of the Guild, with very beneficial results; & bringing back amongst other things over 300 photographs of precious things from about a dozen towns & cities.”

In fact, White spent 30 days touring Italy. His photographic record of pictures and buildings relating to items in the Ruskin Museum’s collection, and Ruskin’s copious writings, were later mounted and made available for study in the museum’s library. White also gathered a great deal of useful information about how the museum’s numerous watercolour studies related to other pictures and buildings of significance, knowledge which doubtless benefitted curator, visitor, and reader alike in the years that followed.

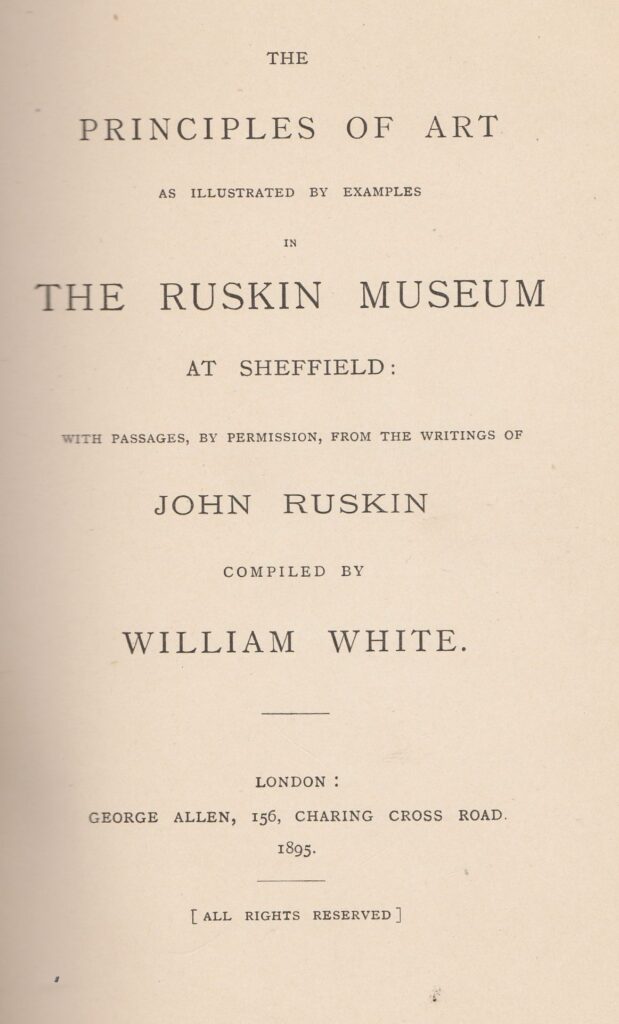

This research tour, and other field trips, would bear their finest fruit in White’s magnum opus, his great catalogue of the pictures in the collection, The Principles of Art, as illustrated by examples in the Ruskin Museum, at Sheffield, with passages, by permission, from the writings of John Ruskin (London: George Allen, 1895), price 10s 6d.

Cathrine Morley accurately describes the book as “a concordance between the Museum and Ruskin’s work” (p. 227). It took White much longer to complete it than originally envisaged. It was described in September 1892 as shortly due for completion. The same newspaper report gave one of the reasons for what was even then considered a delay: “[White] has trouble in making the descriptions sufficiently lengthy to be instructive, and at the same time not too comprehensive” (Sheffield Independent, 1 September 1892), a conundrum that ultimately he arguably failed adequately to resolve. More than two years later, it was reported that, “It has been somewhat delayed owing to the preparation of the illustrations” (Sheffield Independent, 7 February 1895).

In more than 600 pages of text, White elucidates Ruskin’s ideas in an impressively copious and close analysis of the pictures in the museum. It is not at all the “brief concordance” White claimed it to be (p. xii). Each chapter focused on a different subject, and was arranged according to chronology and place. In tackling landscape painting, he drew heavily on Ruskin’s writings, but added valuable observations of his own drawn from his original research. Overwhelmingly sympathetic to Ruskin’s theories, he nevertheless issued clarifications, sometimes with unnecessary force of argument. More than 20 pages (pp. 62-82) were dedicated to Verrocchio: White’s detailed notes on the “Madonna and Child”, which Ruskin had put at the centre of the museum at Walkley when he rearranged the display in 1879, explained how recent treatment to conserve the only original Old Master painting in the collection had revealed another figure and traces of other pigments that the artist had decided to paint out (see p. 75). He concluded that the work was Verrocchio’s alone, and that it owed nothing to his famous pupils.

Upon the book’s publication, towards the end of 1895, the Sheffield Evening Telegraph declared that, “no man is better qualified to have undertaken such a task. To all disciples of Ruskin the work will be of great value though naturally it specially appeals to those who, living in Sheffield, have such a treasure as the Ruskin Museum at their very doors” (18 November 1895). A review published in the Sheffield Independent is worth quoting at length, as much for the revealing observations of the book’s minor failings as for its justified praise of its merits.

“Visitors to the Ruskin Museum have for long observed the need of a connecting link between the teachings of Mr Ruskin and the practical illustrations of them at Meersbrook Park—a link such as could not be furnished at sufficient length by a mere catalogue, and could not be procured from Mr Ruskin’s works without profound study and careful selection. It is with the aim of supplying this connecting link that Mr White has written the large and comprehensive work now under review. We say he has written it; but it would be nearer the mark to say [as White in fact said himself, that] he has compiled it. Mr White, in his endeavour to bring Mr Ruskin’s writings in touch with the student of the Ruskin Museum, has sacrificed many opportunities of originality, and allows his master to occupy by far the greater portion of these pages. Mr White’s general method is as follows. Taking some work of art in the Museum and his formulation, he first of all introduces some description of the original artist or architect, or a survey of its surrounds and the influences which tended to produce it. He afterwards quotes extracts from Mr Ruskin to explain how the Ruskinian canons of criticism are to be applied to the work, and how its merits or defects are to be recognised according to these canons. The advantages of such a system can be seen clearly at first glance. Each work in the gallery becomes a practical means of art criticism, and the broad principles of painting or architecture as applied to it by the most consummate of critics, are placed luminously before the observer. At the same time, Mr White’s plan is not wholly without blemishes—blemishes, however, which could be readily modified. While enabling the student to perceive the art principles pursued or controverted in each separate work, the system fails to give a sufficiently connected idea of those principles. This, however, could be done by introductory chapters, and although Mr White has many admirable introductions, a large part of which he has written himself, he does not succeed in marshalling these main principles so as to bring them conspicuously and more or less simultaneously before the student’s eye. He might, for example, have summarised Mr Ruskin’s canons as laid down in the Seven Lamps of Architecture, or quoted some portion of the second volumes of Modern Painters, where the characteristics of the highest art are treated in a definite order. It must, however, be recollected that if Mr White’s book loses in clearness from the want we have indicated, it gains in variety, and is quite without that text-book flavour which has so frequently condemned works of its class. We can now proceed to cast a glance at the plan and progress of the book. Mr White begins with a characteristically Ruskinian introduction—at once an apologia for Mr Ruskin’s convictions, and an emphatic reiteration of them. Mr Ruskin has strong, even violent views, and it is only his absolute belief in their perfect rightness which absolves him from the charge of intolerance. No one is so lavish in his praise, or so remorseless in his blame, as the author of Modern Painters. But there is a force of intense sincerity behind both praise and censure, which drives the most prejudicial reader, if not into submission, at least into admiration. The whole tone of Mr Ruskin’s teaching is admirably compressed and outlined in this introduction—one of the very best portions of the work. The part following the introduction is devoted to painting, and is divided into three sections—the Florentine school, the Venetian school, and other schools. The selection of pictures described may seem to a casual reader somewhat arbitrary; but Mr White has strictly confined himself to those painters represented in the Museum—those, that is, who are best calculated to illustrate Mr Ruskin’s principles. A large share of attention is naturally devoted to those painters—Tintoretto, Verrocchio, Carpaccio—whose fame Mr Ruskin has gone far to re-establish. Of all works in the Museum, the greatest space is, of course, given to Verrocchio’s Madonna—the chief treasure under Mr White’s care.” (Sheffield Independent, 18 March 1896; my emphasis)

The review contains some valuable observations about Ruskin’s writings as well as White’s book, but it is particularly worth pausing to consider the lines I have emphasised: “While enabling the student to perceive the art principles pursued or controverted in each separate work, [White’s] system fails to give a sufficiently connected idea of those principles [… and] he does not succeed in marshalling these main principles so as to bring them conspicuously and more or less simultaneously before the student’s eye.” This is essentially the criticism that Ruskin scholars have rightly levelled at White’s curatorial practice (even if White was not wholly and exclusively to blame for it). The fixed focus on individual works, and the careful categorisation of items and objects by type, subject, place, and/or chronology, disrupted the broader, subtler, more meaninful, and idiosyncratically Ruskinian connections that were so much clearer at St George’s Museum in Walkley. Without it, the moral value of exhibits—Ruskin’s most cherished measure of worth—were obscure and apparently less relevant.

And yet, as William Sinclair of the Glasgow Ruskin Society wrote, “To the student of Ruskin who is anxious to learn of the many-sidedness of the Master of St George’s Guild, it is a book that one cannot afford to remain unread. It is no mere catalogue, but a comprehensive study of the functions of a Museum of marked individuality, and contains an accurate account of the chief Masters of ancient Italian art, with illustrative examples and descriptions of their works, besides concise biographical details.” (William Sinclair, “The Ruskin Museum at Sheffield: What It Is, and What It Might Be”, in Saint George, vol 5, no 20 (October 1902) pp. 263-282, specifically pp. 268-269)

But not everyone agreed with these positive assessments. The Saturday Review thought the book a useful “synopsis and concordance”, but found White’s contributions “often obvious and sometimes annoying” with “padding” that was condemned as “simply an insult to the reader” (29 February 1896).

A highly critical review in an issue of The Studio: International Art (volume 8, 1896) by the American art historian Mary Logan (Mrs Bernard Berenson) (1964-1945), asserted that “it would be hard to imagine a more inconvenient and unsatisfactory” book of selections from Ruskin than White’s nearly 700-page tome—“inconveniently heavy for the museum visitor, unsatisfactory to the home reader because it is in the form of a catalogue” (p. 249). Though she described White as a “devoted Curator”, she found that his editorial comments and explanations “half-spoiled” the joy of reading Ruskin’s prose by “drag[ging]” the act of reading “down to common earth” and what she considered her own balanced assessment of Ruskin’s merits and limitations led her to conclude that White was “not the man to whom we may look for an estimate of Ruskin’s genius and mission”. She also criticised the reproduction of a work by Newman, condemns J. W.Bunney’s painting of St Mark’s, Venice, as “accurate but spiritless”, and dismisses the suggestion that the Madonna and Child was the work of Verrocchio.

Inevitably, given the book’s cost and size, it was not a commercial success. It was noted in 1895 that in order to avoid making a loss on the cost of publishing it, the book’s price would have to be increased from 7s/6d to 10s/6d per copy, further revised up in 1897 to 25s per copy. In 1898 George Allen gave the museum 96 bound copies of the book, and 478 unbound copies, plus six steel plates and 15 photographic negatives relating to the publication. At the same time, the Ruskin Museum Committee noted that it now possessed 984 copies of the Handbook and 552 copies of the Principles of Art (470 unbound and 74 bound copies).

Nevertheless, long after White’s departure as curator the book remained important to many people who cared about the museum. It was even referred to by loyal visitors in defence of the museum and its cost to ratepayers. A letter that appeared in the Sheffield Independent in 1931 from someone calling themselves “Old Student”, wrote:

“It would take up too much of your valuable space to give a tithe of the exhibits which are described in a book of 634 pages by Mr William White which I have before me as I write, but a few of the most interesting exhibits are The Verrocchio Madonna, the only old master of the Italian schools in Sheffield or district; Turner’s Liber Studiorum, Holbein’s Dance of Death; original volumes, illuminated manuscripts, including the Missal Album of Lady Diana De Croy; unique specimens of minerals and precious stones, etc., the whole display[ed] to illustrate the teachings of Ruskin. I am sure anyone interested, whether individually or in part, may be sure of all the help and courtesy that the acting curator, Miss G[enevieve] Pilley, can give.

“That this rare and valuable collection of gems of nature and art was intended for the earnest student especially the artisan student, was the desire of Professor Ruskin. It was his admiration of the work of the Sheffield cutler that led him to place his first school here. Anyone visiting need have no fear of being regarded as lacking in knowledge, for is not the essence of Ruskin’s teaching humility in searching after truth?” (21 October 1931)

J.M.W. TURNER

White is always strongest when writing about Turner in The Principles of Art. The Appendix presents notes on 50 of Turner’s sketches and drawings (pp. 593-607). It was published in 1896 as a standalone pamphlet. White demonstrate a deep knowledge of Turner’s work and critical appreciation of his technical skill as an artist.

The main public rooms of the museum in White’s day were all upstairs in Meersbrook Hall: the Picture Gallery, Minerals Room and Library. However, new rooms were introduced on the ground floor. The most notable was the Turner Room, near the main entrance, and opposite the Committee Room (which after White’s time was turned into the Lecture Room). White introduced the Turner Room in the winter of 1891 in order to display, in chronological order, the collection of 50 of Turner’s works which he had written about in his appendix to the Principles of Art. In something of a personal triumph, he had secured them on loan from the National Gallery. Representing all periods of the artist’s career, they had never previously been exhibited.

The lack of public access to Turner’s work had long been bemoaned. It was an issue raised by Ald. W. H. Brittain who complained in Edinburgh at a meeting of the National Association for the Advancement of Art, that only 500 of the 18-19,000 items in the Turner Bequest were available to the public. In response, the National Gallery’s authorities mounted 300-400 more drawings.

Likewise, an article on “Hid Treasures” had appeared in the Sheffield Independent in 1889, in which it was regretted that so much of Turner’s work was not on public display (5 October 1889). Elijah Howarth, curator at Weston Park Museum, responded by letter to say that some Turners were in fact on loan to the Mappin Art Gallery until July 1890. A correspondent in Heeley (adjoining Meersbrook) thought that some of Turner’s pictures could profitably be placed at Meersbrook in support of the new Ruskin Museum. White managed to negotiate precisely that, having approached the trustees of the National Gallery in October 1891. White was granted permission to select 50 drawings illustrative of Turner’s technique dating from about 1775 onwards. Fourteen views, representing Oxford, Tintern Abbey, Warkworth Castle and other places, dated from the period before 1800. Thirteen pictures were from 1800-20. White also selected “The Burning of the Houses of Parliament” (1854) and items from Turner’s final years.

For White to have secured the loan was no mean achievement. It is a measure of his tenacity, imagination and creative energy. Sheffield in general and the Ruskin Museum under White in particular had thus played a part in making more of Turner’s work available to the public.

The Turner Room officially opened on 15 December 1891 and the exhibition was scheduled to last a year. However, a further year’s extension to the loan was subsequently granted, and it is likely that the exhibition remained open until at least late 1894 because the exhibition was referred to by Albert Sprigg in his article in The Windsor Magazine published in February 1895. Sprigg noted,

“The drawing of Tintern Abbey is practically complete, and one of a storm on the Alps is essentially typical in its treatment. Of great interest, too, is a sketch of Inveraray, which was the first study for the subject in the Liber Studiorum series, it having been previously supposed that Turner made no sketch for it but engraved it direct.” (p. 140)

This insight that “Inveraray Loch Fyne: Morning” was a study towards the Liber Studiorum, issued 10 years later, was one of several keen critical observations made by White. As we shall see in the third part of this blog, White continued to engage with Turner scholarship in the years after he left the Ruskin Museum. (The room itself remained in existence into the 20th century, and showcased the museum’s significant collection of Turner engravings and watercolour copies of his work.)

WHITE AS DONOR

Perhaps the best kept secret about White is the stunning generosity of his personal donations to the Ruskin Museum, something which is impressive both in its scale and scope. Thanks to the second of the RMC’s minute books, it is possible to be precise about what he gave the collection between March 1893 and his departure as curator in 1899. His philanthropy encompassed photographs, chromo-lithographs, engravings, pencil drawings, pages of medieval manuscript, books (some of them rare), copies of journals and magazines with articles of interest, and hundreds of minerals of many varieties.

To survey the detail: in October 1891, White presented the Guild with a bust of Ruskin, the sculptor of which is not identified, but he intended it for the museum’s loan collection.

Among the books he gave were some especially fine and rare volumes, such as the second edition of Thomas More’s Utopia (1617) “in the original Latin form” (3 August 1893), and an English translation of the same book dated 1685 (2 August 1894). He donated The Historie of St George of Cappadocia (1633) by Rev. Peter Heylyn (1599-1662), which contained a list of all the Prelates of the Garter ((6 October 1898). He also gave T. Duffus Hardy’s Official Report upon the Archives of Venice (1866), H. R. Fox-Bowen’s Sir Philip Sidney, Type of English Chivalry in the Enlightenment Age, and the Rev W. Tuckwell’s Tongues in Trees and Sermons in Stones (19 November 1895); Memoires de Marmontel, published in Paris in 1805, in four volumes, and W. J. Loftie’s Lessons in the Art of Illuminating (1894) (5 August 1897); the third edition of The Story of a Great Agricultural Estate (1897) by the Duke of Bedford (5 May 1898); and Mrs Charles Heaton’s The Life of Albrecht Durer (1881), and J. O. Halliwell’s book on Sir John Mandeville (1839) (4 August 1898). Then there were books about Ruskin himself, such as Charles Waldstein’s The Work of John Ruskin: its influence on modern thought and life (2 May 1895) and Patrick Geddes’s John Ruskin, Economist (4 May 1899). He also donated 24 photographs of Celtic ornaments from the Book of Kells and other sources (2 August 1894).

This suggests that White was a keen collector in his own right. Indeed, after his death, a catalogue was compiled of printed books and a few manuscripts he had owned, comprising historical and bibliographical literature, and books on art and natural science. His personal collection included first editions of Jane Austen’s Emma, De Quincey’s Opium-Eater, Coleridge’s Biographia Literaria, Milton’s Paradise Lost, and volumes by Thackeray, Dickens, Kipling, H. G. Wells, George Crabbe, the poets Christopher Smart and Mark Akenside, and the dramatist Thomas Otway. He also owned books illustrated by Thomas Bewick, Thomas Rowlandson, and Henry Alken; a presentation copy of Cruikshank’s The Bands in the Park (1856); Hobson’s Chinese pottery and porcelain; a second edition by Chippendale (1755); Taunton’s Portraits of Celebrated Racehorses; unspecified Kelmscott Press publications and eighteenth-century French books; a collection of C17th and C18th tracts and poems, and Spanish literature relating to voyages and colonisation. The lot was sold at auction by Sotheby’s at 1pm on Monday, 27 March 1933, and the two days following.

White was particularly generous in donating minerals to the Ruskin Museum. At first, he made an unspecified loan from his own collection (6 August 1891), but thereafter he made simple gifts. These included examples of labradorite, opal, agate and fluor (7 September 1893); calcite, chalcedony, and an emerald in matrix from Australia (7 June 1894). In August 1895, White gjfted a significant haul of “110 Minerals including 9 very fine polished slabs of Labradorite, 9 choice specimens of precious opal, 5 varieties of common opal, 3 of native gold, 1 of silver, a large beryl, several examples of garnet, topaz, quartz, crystals, fluor, calcite and copper; 20 agates […] 2 fine mocha stones” as well as rubies, rose-quartz, polished flints, and jasper (8 August 1895). Three months later, another gift was recorded, this time consisting of a moss agate and a series of eight pearls of various colours and forms with shell from the Don, near Aberdeen (19 November 1895). A year on, he gave examples of lapis lazuli from Persia, native silver from Norway, smithsonite from Greece, and quartz crystals containing specular iron and chloride (30 November 1896). Another year on, he gave a block of Icelandic Obsidian, wood opal from North Queensland, stalactite calcite, stalagmite calcite, quartz, another mass of quartz from Switzerland, and some polished calcite stalagmite from Knaresborough (7 October 1897). In August 1898, he gave, among many other minerals, examples of fluor with enclosed crystals of pyrite, galena, and goethite (4 August 1898).

Among White’s other donations were artworks of his own composition, including two pencil drawings, one of “Santa Maria Maggiore, Bergamo”, the other of “St Ursula’s Arrow” from Carpaccio’s painting, “St Ursula’s Dream” in Venice, both of them almost certainly made during his summer research trip to Italy in 1892 (3 August 1893). He also donated copies of the Architectural Review for February and March 1898, containing a pair of articles by himself on the early mosaics of St Mark’s, Venice, illustrated with drawings in the Ruskin Museum (5 May 1898).

It is certainly the case, as we saw last time, that White had inherited a considerable sum of money with which he could indulge his interests. But such generosity and personal investment in the museum’s collection goes far beyond the contribution of any ordinary curator, and should put beyond doubt any question as to his level of commitment.

The depth of his knowledge, built on dedicated study and detailed research, and shared with visitors to the museum and readers of his three published guides, also testify to his hard work, ability and sincerity.

But he was careless of his council employers, and loftily dismissive of local residents who made casual visits to the museum and made up the bulk of those who passed through the doors at Meersbrook Hall.

Next time, in the third and final part of this blog, we’ll examine White’s contribution to the illuminated address commissioned to celebrate Ruskin and his achievements on his 80th birthday, and investigate how it contributed to increasing tensions between White and Sheffield City Council. We’ll explore White’s troubled relationship with the city, and how this eventually boiled over into a dispute which ended in his dismissal. Finally, we’ll look at what White did after he left the Ruskin Museum.

Please send feedback to contact@stuarteagles.co.uk