“Is this a holiday?” Flavius asks sarcastically in the opening lines of Julius Caesar. Thanks to Ruskin, the boys at Manchester Grammar School were unexpectedly granted half a day’s holiday in December 1864, a fact apparently long since forgotten. By careful examination of a range of sources, Stuart Eagles reconstructs Ruskin’s visit to the school and finds much that is missing in the official record …

-

“LIKE A BIG SCHOOL-BOY”:

RUSKIN’S ADDRESS TO MANCHESTER GRAMMAR SCHOOL

For Prof Dinah Birch, the authority on Ruskin’s educational thought, on the occasion of her receiving the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Ruskin Society of North America

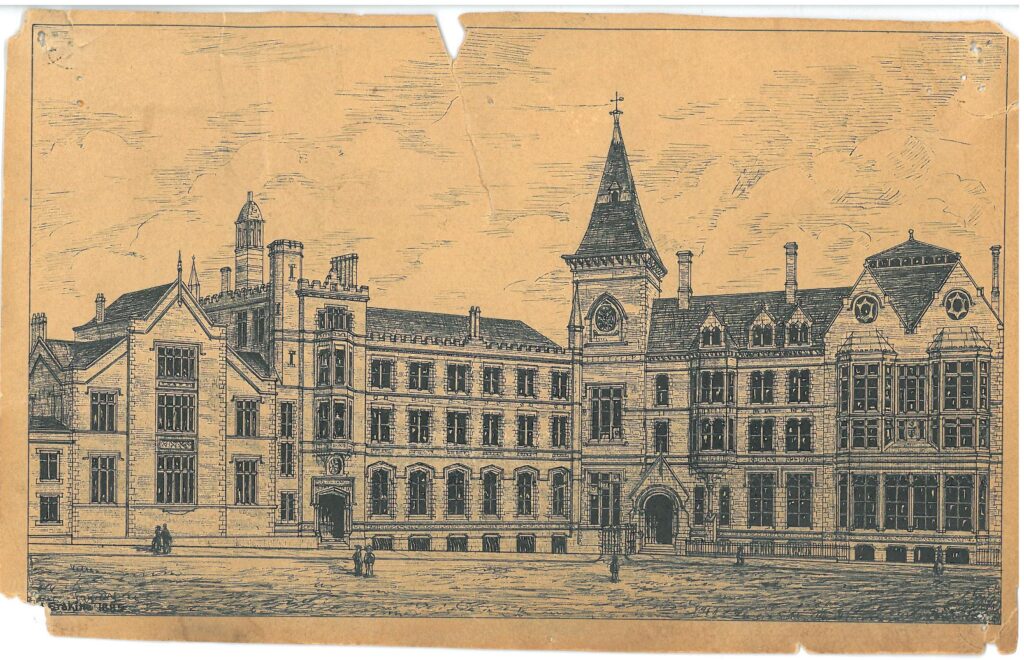

Buried at the back of volume 18 of Cook & Wedderburn’s Library Edition of Ruskin’s Works is an account of the address Ruskin gave to the boys of Manchester Grammar School on the afternoon of Wednesday, 7 December 1864 (pp. 555-557). Ruskin’s editors present a slightly shortened version of the report that appeared in the Manchester Examiner (8 December). On the previous evening, Ruskin had addressed a reportedly crowded but select audience at Rusholme Town Hall, where he had spoken on “what to read and how to read it” in his “Of Kings’ Treasuries” lecture, later published in Sesame and Lilies (1865).

Manchester Grammar School

Manchester Grammar School

Cook & Wedderburn cosign the Examiner’s opening remarks to a footnote. We are told that Ruskin was “met with a most enthusiastic reception from the boys”. There were also unnamed guests present to hear him, “including a few ladies”. A source that was not consulted—the report of the same date that appeared in the Manchester Courier—adds the detail that Ruskin had arrived at the school at about 4pm. That report supplies a substantial amount of additional information, and taken together with another report, from the Manchester Times of 10 December, it is now possible to give a much fuller account of Ruskin’s visit to the school.

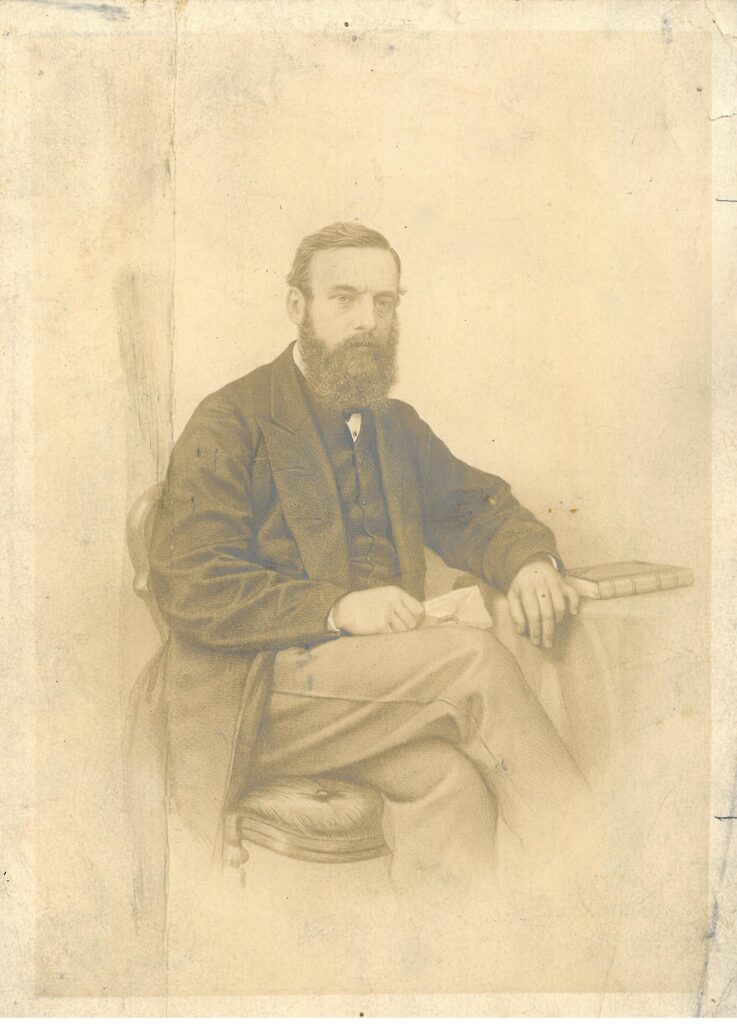

Ruskin’s host was the school’s energetic and successful High Master, Frederick William Walker (1830-1910). Walker had been in post since 1859, and would remain until 1877, when he left to become High Master of St Paul’s School in London. He rapidly improved the standard of teaching at both schools. In Manchester, he expanded the curriculum to include scientific subjects. The school roll trebled from 250 to 750 pupils between 1862 and 1876. Walker was obliged to introduce an entrance examination. He also secured the school’s finances by taking in some fee-paying pupils (from 1867). He had been an undergraduate at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, and briefly became a Fellow there—as, indeed, would Ruskin himself, after his election in 1869 as Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford.

Frederick William Walker

Frederick William Walker

(with thanks to Manchester Grammar School)

The Manchester Courier reported that Walker opened proceedings on 7 December by saying to the boys that Ruskin, “a gentleman of whom they had heard that morning, had with the greatest kindness assented to come amongst them and to speak a few sentences to them”.

Following the Examiner, Cook & Wedderburn record that in Introducing Ruskin, Walker remarked that

“very few of the young people would understand the value of what they were going to hear; but they might take his word for it that Mr Ruskin’s words [the Courier says “observations”] would linger in their minds when they became men as a pleasant memory. Some among them, he hoped, would become in after years earnest and reverential [the Courier says “earnest and diligent”] students of Mr Ruskin’s books; and he trusted they might be helped towards the better understanding of them [“the full measure of his meaning” (Courier)] as men, after hearing Mr Ruskin; as he himself felt that he could understand those books better after the short opportunity he had had of hearing Mr Ruskin the previous evening” [i.e. at Rusholme, where Ruskin had spoken “Of Kings’ Treasuries”].

Cook & Wedderburn do not tell us, as some of the Manchester newspapers do, that this was followed by applause. Ruskin’s editors also omit the detail that he “mounted a form in the middle of the room in order that he might be the better heard” and that, as he did so, he was “again loudly cheered” (Manchester Times). According to the Courier Ruskin said that he

“came there with great diffidence to speak to boys, for in speaking to boys greater care should be exercised than in addressing men. Men could use their judgement as to what was right or wrong, but it was a serious thing to say anything that might be wrong to boys, who could not so well judge, and who might be warped and misled at the most important period of their lives. This is what he decided to impress upon their memory.”

We rejoin Cook & Wedderburn:

“MR RUSKIN said he felt it to be a rather awkward introduction [i.e. from Walker] that the boys were to attach faith in what he was about to say on credit. He did not wish this at all. He wanted them to think over what they heard, and that which was felt to be pleasing and useful at the time might be rendered valuable to them. Boys could only be taught by those who had their sympathy, and they knew this themselves very well. It must not be expected that they could be taught much that was very difficult or disagreeable; but they would take that which they felt to be pleasant and useful, and work at it with all their hearts. He had come down with great diffidence that afternoon, because he had seldom the privilege—and he spoke seriously—of addressing boys. It was long since he had been amongst them, and he felt that he ought to be most careful in what he said. Men knew right from wrong; they could pass judgment on what was said to them, and know whether to attend to it or not. But a boy had to attend to all that was said to him. If the speaker said what was wrong he did it at his peril; but it was also at the boy’s peril.

“It was usual to say that―‘boys would be boys’: they could not be anything else. But if by the expression it was meant that a boy is something light and frivolous, he did not believe it.”

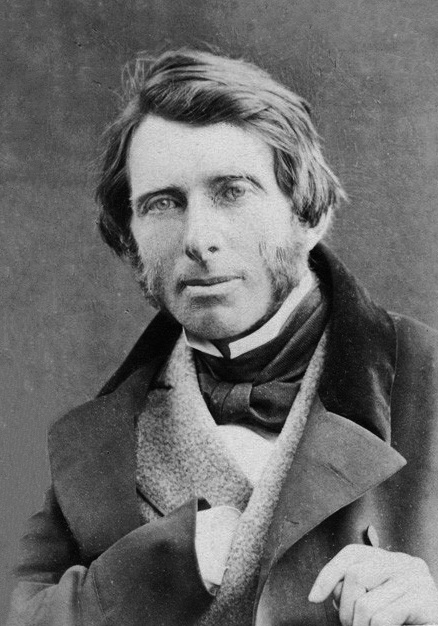

John Ruskin

John Ruskin

Significantly, the Courier reported that Ruskin added here that he also took the expression to mean that boys

“could not help being headstrong and careless, and not doing that which they should do. He did not believe that view of the matter at all. He believed that boys would be boys because they ought to be so, and they should play rightly as well as work rightly.”

There is some disagreement in what came next. Cook & Wedderburn, following the Examiner, reported Ruskin as saying:

“The boy ought to be in all ways a true boy—eager to play and ready to work. He ought to play more than a man, but we made him work harder, and we never gave him work interesting enough for him.”

According to the Courier, Ruskin said that the boy:

“had to work more, comparatively speaking, than a man; and in school there was too much work and not play enough.”

Back to Cook & Wedderburn:

“This, however, was all being corrected now. Boys now were being allowed to play; nay, in our great public schools they were being compelled to play. Some boys never wanted to play, and could not be made to play, and these were not the right sort of boys at all [they were “the most difficult boys to deal with” (Courier)].

“The one thing they had to recollect in working was this—and he believed very few people would tell it to them—that it is just at this time of life that their work is most important.”

Here, in a footnote, Cook & Wedderburn point to paragraph 125 of Ruskin’s lecture, ‘War’, published in The Crown of Wild Olive (1866), in which he states, “No good soldier in his old age was ever careless or indolent in his youth”, only “grave and earnest”: see Works, 18:486.

Cook & Wedderburn’s report continues:

“It was terrible to him to think how lightly people made of boys’ life. They thought and said, ―‘It does not much matter; he is but a boy; he can make it up afterwards.’ No; all through life they could not make up life that they had once lost. In the will of Providence, so much time, and brain, and heart, and power, was given to man, and whatever he loses there was no regaining. He might make any efforts afterwards, but those same efforts, if not required to go over old ground, might have carried him further ahead.”

According to the Courier, Ruskin then said, “The foundation of future character was laid in early years, and if this foundation was laid loosely the consequences would be constant after-stumbling, and breaking their noses throughout the rest of life.” This provoked laughter.

Back to Cook & Wedderburn for a somewhat different version:

“And what was worse, the habits formed in boyhood influenced his after years; any bad habit acquired then stamped its influence upon all his after life. They must remember, then, that the habits formed at school would constitute the foundation of their future character, and would prove stumbling-blocks or supports according as they were bad or good. They might strive to shake themselves free, but these influences would be sure to last.”

(The Courier added that “no after misfortune would be able to remove” the foundation of good habits, “but the opportunity for doing this once lost could never be recovered”.)

“To speak of himself, he might say that when a boy he did not [hand-]write well, nor could he to this day [“and to the end of his days he would mourn that circumstance” (Courier)]; and so the previous evening, when he was lecturing [at Rusholme, “Of Kings’ Treasuries”], he felt it a drawback that he could not read some passages of his own manuscript with perfect ease.

“Much more in greater things—much more in the foundation of the moral character—was it important to pay attention to the formation of such habits only as are desirable. In illustration of his remark he instanced the leaning tower of Pisa. The architect did not build it so on purpose. The foundation was laid on soft, unequal ground, and when the first storey was erected the building began to incline a little. The architect strove to remedy this step by step, and the result was the building as it can now be seen.

The Leaning Tower of Pisa

The Leaning Tower of Pisa

“It was so in life,—begin on a faulty foundation, and all would go crooked; while, if the foundation were right, our course would be straight whether we wished it or not. [“They should attach importance to every action of their lives.” (Courier).]

“The best thing a boy could learn was confidence in those about him. His companions should be those who had gained his confidence, whom he could love, and with whom he could be entirely open. No habit was so important to a boy, or to a man; but the habit was best formed in boyhood. [“They should not let things into one ear, as it were, and out of the other.” (Courier)] He did not ask them to blurt out everything that came into their heads; but let them get into such an open habit of mind that those who were worthy of their confidence could read them as they could a book. It would protect them from much evil. There was nothing so noble in manhood as that free, open front which fears no man’s eye. There were people going about—jugglers and others—who profess to look into people’s minds, and people said how dreadful it would be if this power were really possessed by us. That was not the way it should be. [Here, the Courier reported Ruskin as having put the point the other way around: “some people would say, ‘How good it would be if we could so [i.e. see into people’s minds]!’ That was the way it should be; they should lay their minds open to those whom they loved.”] We should have a mind that we should long for certain people to look into, and be sorry if we could not do so with those we love.”

The account reproduced by Cook & Wedderburn becomes rather vague at this point, and reads as follows:

“There were certain things it was better should be worked out of us, and by the habit of free and unrestricted intercourse [i.e. conversational exchange] we grew stronger and better.”

The Courier is much more detailed in its reporting here. Crucially, it records the extended, autobiographical and Biblical metaphor that Ruskin used to make an important point about mischief. It is a significant paragraph altogether missing from any other published account. It is therefore reprinted here in bold.

“Probably they [i.e. the boys] would recollect the saying about new wine in old bottles. There was a curious type of what the value of openness was—he was a wine merchant’s son and ought to know something about it. They knew that the bottle that Christ speaks of is made of skin, and when new wine was put into it it burst. The bottle ought to be seasoned in order that it should be strong enough to resist the power of the wine. Teachers were always putting old wine into new bottles; they were always thinking they could put old heads on young shoulders. Like effervescing liquids such as cider and champagne, boyish nature must come out one way or another; in preparation to the power of the effervescence out comes the cork, and the mischief comes out with it. If the mischief did not come out [then] it fermented and poisoned, and the bottle burst. That was what took place in the whole being of man—the mischief must come out in one way or another. We were all mischievous, and some of us ought to be ashamed of what mischief was in us. But get thoroughly in the habit of telling all that is in you and you get rid of mischief, and gain power and strength to be right. Recollect the saying of Horace, ‘Nulla pallescere culpa’” [i.e. Horace, Epistles, I.i, 61].

Cook & Wedderburn’s report also quotes Horace’s words, and proceeds with Ruskin’s explanation of its meaning:

“We might grow pale from various causes, it might be from overwork, and that was a bad way[; “and for want of exercise, which was also a bad way” (Courier)]; but the worst way of all was the growing pale because of something on the conscience.”

Cook & Wedderburn end their account here. But the Manchester Times for 10 December goes on to tell readers that “Mr Ruskin concluded with a few words of encouragement to the boys amidst loud applause”. The Courier again gives us significant new detail, reporting (and again this is reprinted here in bold):

“We were too much in the habit of saying that boys could not bear discipline, but before saying this we ought to discipline ourselves. They should remember and bear with them the Latin sentence of the great heathen [i.e. Horace]—Quanto quisquis [sic] sibi plura negaverit ab Dis plura feret [Horace, Carmen saeculare, III.xvi, 21-22]—‘By so much as man denies to himself by so much shall he have power from God.’ (Cheers.) Let them recollect this, and it would help them in many a dark hour.”

The Manchester Times continues the account with information not published by Cook & Wedderburn (again reprinted here in bold):

“The High Master thanked Mr Ruskin, in the name of the boys, for his address; and three hearty cheers having been given for the distinguished visitor, Mr Ruskin said, as a practical application of his remarks, he would ask Mr Walker to give them a holiday.

“Mr Walker, in reply, said the boys might have half a day to-morrow (Thursday), an announcement which called forth the most vehement cheering.”

And, no wonder. The report concludes that shortly afterwards, the visitors left the school. Presumably that included Ruskin himself, who must have departed a hero, at least for the next 24 hours or so.

Why Cook & Wedderburn omitted such a charming detail can only be guessed at. Perhaps they thought it trivial, but given that Ruskin reportedly promoted the idea as the “practical application of his remarks”, such a view would seem misjudged. Perhaps they thought it cast Ruskin in a poor light. But if they thought that, they surely missed his point. Perhaps they wondered, as I did myself, whether Walker had been as good as his word. Might he have changed his mind as soon as his distinguished visitor had left the building?

So I consulted the archives at Manchester Grammar School, and received the most helpful replies from Rachel Kneale. I had asked whether a school logbook might confirm whether the holiday was given, but she told me that nothing of that sort had survived from the period.

However, the school magazine, Ulula, though it had not started howling until the 1870s, published two separate and relevant reminiscences submitted by anonymous Old Mancunians more than a quarter-of-a-century after the events had taken place. They confirm that the half holiday was given. Walker’s hope that Ruskin’s message might be better appreciated by the boys in adulthood was not apparently fulfilled, but the “practical application” of Ruskin’s remarks would certainly linger in the memories of at least two of them.

The first testimony was published in March 1890:

“These reminiscences of a bygone age recall two instances which still stand out, both fresh and fragrant, in the brain amid the passage of time. One was an address to the boys by Mr Ruskin. I cannot remember the subject, but well even yet do I recall his appearance, and, needless to say, added mine to the cheers for the holiday he begged and obtained for us.”

The second set of recollections adds an important detail missing from both Cook & Wedderburn, and all the contemporary press reports, namely that the boys had been obliged to sacrifice their normal half-holiday on a Wednesday afternoon to hear him in the first place. Assuming that Ruskin understood this fact himself, his plea might be regarded in a somewhat different light. Nevertheless, it also puts into perspective all the applause and cheering with which the boys greeted him from the start. Here, then, is what was published in Ulula in July 1898:

“Another red-letter day was when, on the invitation of Mr Walker, we were honoured at the school by a visit from Prof. John Ruskin, one Wednesday afternoon (our half-holiday). I don’t think I understood and enjoyed what Mr Ruskin said as I ought—for one thing, his speech was far too rapid,—but all of us appreciated the climax, when he asked Mr Walker to give us another half-holiday for the one we had lost through his coming. We then cheered him to the echo, and he, like a big school-boy, heartily joined in with us. I am sure it gave him as much pleasure getting us the holiday, and seeing how we enjoyed the prospect, as much as the thing itself did us.”

Separate to the main report in the Manchester Courier came this short assessment of Ruskin’s address to the boys. “The speech”, the paper commented—

“Sententious, discursive, wise, and overflowing with kindly feeling—is one that defies a summary treatment. It is worth while [sic], however, to note critically the pure and nervous [i.e. vigorous, powerful] English of the speaker, his perfect mastery of language, and his use throughout the entire address of comparatively few words of more than one syllable.”

The clarity and force of Ruskin’s language were vital to his success. Ruskin knew how to shock an audience, and how to provoke it, how to excite and how to entertain, and he also knew how to flatter and gratify. He practiced what he preached, ensuring at his conclusion that he won the boys’ sympathy by giving them, with Walker’s co-operation, the ultimate practical demonstration of how earnestly he had spoken of the value of play in boyhood.

With many thanks to Rachel Kneale, Archivist of Manchester Grammar School, for supplying the images of the school and of Walker, and for giving permission to quote from Ulula.

Send feedback to contact@stuarteagles.co.uk