David Downs (1818-1888) was Ruskin’s gardener and his go-to man whenever one of his many projects needed a boost. Ruskin scholars generally suggest that Downs was a rather put-upon loyal family servant whose nous brought order to Ruskin’s chaotic schemes. But Downs’s heroic efforts made him sceptical about his master’s wisdom, the accounts say, and he increasingly found consolation in a pint-pot.

On 6 March 1878, Downs wrote a letter from Brantwood to Henry Swan (1825-1889), the curator of Ruskin’s museum in Sheffield. Ruskin was then suffering what would prove to be the first of the major mental breakdowns that would blight the final years of his life and condemn him to virtual silence. Swan shared Downs’s letter with the local press, and it is worth quoting in full both because it does not seem to have re-appeared since its original publication, and because a certain tenderness of tone reveals something important about Downs that I think merits a re-assessment of his motivation.

“Dear Mr Swan,—As I have just a few minutes to spare, I take the opportunity to give a line to you about our dear master. I am very sorry indeed to say he is very little better. The following is the report from the doctor this morning: ‘Mr Ruskin’s condition is not materially altered, but he has had a better night.’ Dr Simon [Sir John Simon (1816-1904)] is still here from London, and Dr Parsons from Hawkshead [Dublin-trained George Parsons, the model for Beatrix Potter’s John Town-Mouse], passes every night at Brantwood. It is a most anxious time for us all, as all here love him most dearly, in which I know you all share at Sheffield most heartily. Mr and Mrs Severn [Ruskin’s cousin and carer, Joan, and her husband, Arthur] are here, and are promoting all they know and can do for his comfort and recovery. His illness is entirely from overwork for the benefit of the people, and his anxiety to promote a good cause. I had hoped to have been in Sheffield at this time, but of course nothing can be said about it now.—With kindest regards to Mrs Swan [Henry’s wife, Emily, co-curator of the museum], I remain, yours very respectfully, David Downs.”—Sheffield Independent (8 March 1878).

The key phrase here is “[Ruskin’s] illness is entirely from overwork for the benefit of the people, and his anxiety to promote a good cause.” Of all Ruskin’s servants, none were more actively involved in his “good-cause” schemes than Downs. Downs was almost certainly expressing some degree of self-pity in thus pathologizing Ruskin’s philanthropy. One explanation is that if Ruskin’s illness could be blamed on these schemes, Ruskin might be forced or persuaded to desist from them, and Downs would be let off the hook. But given Downs’s long and loyal service to Ruskin, should we not do him the courtesy of taking this letter at face value? Rightly or wrongly Downs blamed Ruskin’s good causes for making him seriously ill. If Ruskin was to live—or to have a life worth living—he must learn not to lose himself in good causes. It is not a noble stance, but however mistaken Downs might have been, he thought he had Ruskin’s best interests at heart.

In Sketches from Life in Town and Country (1908) the socialist Edward Carpenter, who had met Downs in Derbyshire, called him “the very old-fashioned and John Bull-like retainer of the Ruskin family” (p. 208). Downs worked first as a gardener for Ruskin’s parents, John James and Margaret Ruskin, before becoming the son’s general factotum. According to one witness, Downs considered John James Ruskin a “gentleman” but asked (over a beer) why the son did not spend his money “like a gentleman” too?

Scholars have not explored Downs’s background, so I’ve sought here to fill in some gaps and to provide a more rounded portrait of him.

Downs was born in the parish of Winslade, three miles south of Basingstoke in Hampshire in central southern England. He was baptised in the local church on 2 August 1818. His parents, David Downs, a farmer, and his mother Elizabeth, née Fleet, had married in the nearby parish of Cliddesden on 22 July 1813. Documents at the Hampshire Record Office show that Downs’s parents leased Southwood Farm, which lay between Winslade, Dummer and Kempshott. They were in residence from 1815 until 1839, so it is likely that Downs was born there, and we can say with confidence that he grew up on the farm.

In the 1840s Downs moved to Denmark Hill. He was in his twenties and set himself up as a gardener. On 26 April 1847 he got married at St Giles’s Church, Camberwell. His bride, Maria Cowler (1813-1887), was the daughter of James Cowler, a shoemaker. The census shows that the family lived at a succession of houses near the Ruskins: Herne Hill (1851), 24 Denmark Hill (1861), and 58 Denmark Hill (1871). When Ruskin moved to Brantwood, Downs and his wife lived mostly at Coniston in the Lake District, though Downs was often sent away on missions. Downs had already travelled widely with Ruskin by then: to Keswick in 1867, Abbeville in 1868 (to study market gardening), and to other parts of France and Italy in 1870, for example.

In the 1870s Ruskin dispatched Downs to oversee a wide variety of his schemes in practical utopianism. This oxymoron is apt. If Ruskin provided the lofty ideals and vision, Downs got his hands dirty and literally did the spade-work. These ventures invariably collapsed under the weight of expectation and failed as examples of utopian practice. But as a series of exemplary challenges designed to encourage people to act—to get involved and to do something in response to what was wrong in the world—they fired the imaginations and won the loyal discipleship of a wide variety of followers from Arnold Toynbee to Oscar Wilde, Octavia Hill to the Sheffield communists. But Downs probably only tended to see Ruskin’s disappointment, and no doubt he was on the receiving end of it all too often.

To take only two examples—and subject each to the briefest of treatments—it seems clear that Downs’s attitude changed as he observed the impact of the schemes’ failures on Ruskin, and grew weary of their effect on himself.

Most famously, in the mid-1870s Downs supervised the undergraduate diggings at North Hinksey in the Oxfordshire countryside. This was a controversial scheme that Ruskin, who was then Slade Professor of Fine Art at the University of Oxford, conceived of as an exercise in community service. Directing students’ energies to useful labour, it was the Ruskinian alternative to competitive sports. The villagers would feel a tangible health benefit from improved drainage. And everyone should appreciate a more beautiful and less muddy rural road.

One perspective on Downs’s involvement in the diggings is given by Sir Edward Bagnall Poulton (1856-1943), who was briefly involved in them as an undergraduate. Poulton became a noted biologist, and was the Hope Professor of Zoology at Oxford for forty years from 1893. He was keenly involved in the work of the Ruskinian Oxford University Museum of Natural History. Poulton recalled:

“The disciples were directed in their exertions by Ruskin’s gardener, a man as round and fat as his master was tall and spare—‘the sort of man who walks about with a big belly and a pot-hat’, to quote an ingenious description I once heard of the typical gardener-foreman. But David Downs, who was a capital worker himself as well as an excellent foreman, only possessed the first-named qualification. A plate in Mr Taunt’s recently published work —a valuable record of the Diggings—clearly shows that he wore a soft felt hat.”

Ruskin road-makers at North Hinksey, public road in village, housing, Henry W. Taunt (mentioned on object), North Hinksey, Jun-1874, paper, h 88 mm ? w 138 mm. (Photo by: Sepia Times/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Detail from Taunt’s photograph.

Downs also took on the 13 acres at Totley in Derbyshire which Ruskin purchased in 1876. Ruskin had established what became the Guild of St George in 1871, and one of his aims was to demonstrate the merits of honest manual labour and good husbandry. At Totley, he sought to facilitate the ambition of a group of communist co-operators from Sheffield to live healthy lives in the fresh air of the rural economy away from the industrial smoke, disease and overcrowding of the city. One of the Guild’s Companions (members) described Downs as the organisation’s “Special Agent” though it was not meant as a compliment. The communists first fallen out with each other, and then disputed the authority of a manager Ruskin appointed to sort things out. Sending in Downs, Ruskin instructed that his faithful gardener was

“[…] to have whatever authority I could have myself, if I were there, and deserves it much better, seeing he knows more about the business, and understands my mind, by this time, having lived twenty odd years with me, besides taking care of me when my mind was nobody knew where” —The Brantwood Diary, ed. Helen Viljoan, p. 580.)

Ruskin clearly considered Downs dependable and trusted him, and whatever his faults, Downs seems to have done his best to carry out his master’s instructions. If Downs did not in fact understand or appreciate Ruskin’s good causes as well as Ruskin thought he did, he was not, alas, alone in that. The tipping point certainly came with Totley. Ruskin had been driven half-mad, and Downs could only cope with St George’s Farm if he could turn everyone else out and run it as a modest market garden, which is precisely what he did. When Downs and his wife Maria relocated to Totley, their adult children went with them, George Downs (1848-bef. 1911) and David Downs Jnr (1849-1908), and they probably helped tend the land, too. Nevertheless, David and Maria Downs seem to have lived out their final days in declining health and spirits. David Downs reportedly drank too much beer, and he and his wife seem to have left the farm in 1886 and retired to a property on Abbeydale Road. They apparently relied on parish relief, though in fact Downs’s estate was reckoned to be worth £426 2s 10d when he died on 14 June 1888.

Just to round off the immediate Downs family story, it’s worth noting that about six weeks after Downs’s death—on 26 July—his son George married at St John’s Church, Leeds. George wedded the 27-year-old Mary Mager, the daughter of an Ecclesall engineer, John Mager. The couple moved to a house on Abbeydale Road, next to Totley post office (perhaps the house David and Maria had lived in), and by 1891 George was working as a builder. The couple already had one son, George David Downs, born in 1889. He grew up to be a jobbing cabinet maker. Downs’s other son, David Jnr, an insurance clerk, had married at St Giles’s Church, Camberwell, on 15 April 1870. His bride, Alice Phoebe Bissell, was the daughter of a legal clerk. The couple had five children together, and remained in Sheffield after their move north in the late 1870s.

Downs’s ample proportions, referred to by Poulton, were confirmed by Howard Swan (1860-1919), Henry Swan’s eldest son. Howard knew Downs during the Totley days, and over the years Downs had frequently delivered minerals and other treasures from Brantwood to the museum at Walkley.

“[Ruskin’s] servant Downs was his devoted slave. ‘Downsie-Pownsie!’ he would say, in smiling accents, ‘was he not well? Poor old Downsie!’ as the old man hobbled along slightly rheumatic, when staying at his last home in the St George’s Farm [at Totley], the other side of the hill [from the museum].”

Howard Swan’s recollections try to capture Downs’s accent and way of speaking, and reveal a mixture of scepticism and loyalty in the servant, condescension in the master (and perhaps a degree of snobbery in the reporter).

“Old Downs used to relate many an anecdote of ‘the young Master’, as he called him.

“‘He were a funny man,’ he said; ‘once, when we went back to Switzerland, he says: “Come along, Downsie; let’s go and see if it is still there!” and I trots along’ (the old man puffed in example—he was fat). ‘I wonders what “it” was. Well, we goes down to the lake, and he points and he says, “Yes, there it is—there it is, Downsie!” “Where?” says I. “Why, there! Don’t you see it?” I saw nothing except an old stump in the water. “Why, the old stump; there it is, the same as ever! I used to come and sit there fourteen years ago! And there it is!”’ A curious example of Ruskin’s vividness of remembrance of detail.

“‘We were marching along in the Alps,’ said Downs, ‘him and Mr Ward. [I.e. William Ward (1829-1908).] Ah, Mr Ward was a gentleman; he could speak French like a native. Well, they were walking along, and talking, talking, talking—and I was getting hungry, I was. So I asks, “Beg pardon, sir; is it time for dinner yet, sir?” “No, not yet!” Well, I s’pose he saw my face fall, for he says, “Oh, it’s you who are hungry, eh, Downs? Well, go along on and order lunch; there’s the inn over that next hill—and order us something nice, there’s a good Downsie!” So I went, and I knew what he liked, so I ordered a dish of mushrooms and milk—and it was good, I promise you.’ Such was the master to his man.” —Qtd in Works of John Ruskin, ed. E. T. Cook & A. O. Wedderburn, vol. 34, p. 718.

Howard Swan’s memories were originally published in the Westminster Gazette following Ruskin’s death in January 1900. When most of the report was reprinted in the Sheffield Independent, these paragraphs were left out—though no editorial cuts were acknowledged. The newspaper was careful not to offend anyone who remembered Downs personally, including relatives who lived in the area.

Another piece of personal testimony is rather more positive, though again it comes from that earlier period before Ruskin’s first major breakdown. Following a visit to Brantwood in the summer of 1876, the Harvard Professor, Ephraim Whitman Gurney (1829-1886), told the academic Charles Eliot Norton (1827-1908), a friend of both Gurney and Ruskin, that:

“Instead of walking home as we had arranged to do, the faithful Downs, who wished his duty conveyed to you all, insisted on rowing us back as well as over. It was pleasant to hear him talk of his master and of his own pride in appearing in person in Fors.” —Letters of John Ruskin to Charles Eliot Norton (1904), vol. 2, p. 135.

Downs never refused to take Ruskin’s instructions and perhaps he even believed that he could better take the strain of these ill-advised schemes than his misguided master? By the time Downs was sent to take charge of Totley, Ruskin must have seemed broken. There is little doubt that Downs colluded in the failure of the communistic experiment there, but the real tragedy is that Downs seems to have thought that he was acting in Ruskin’s best interests by doing so. Downs thought that he was rescuing Ruskin from the hubris of a dangerously generous and recklessly idealistic philanthropy. Edward Carpenter called him ‘the Angel-gardener with the Flaming Pitch-fork’ (Sketches, op. cit., p. 208). Old Downsie did his best and in all good faith acted as Ruskin’s gardener-angel.

Post Script: A Family Connection

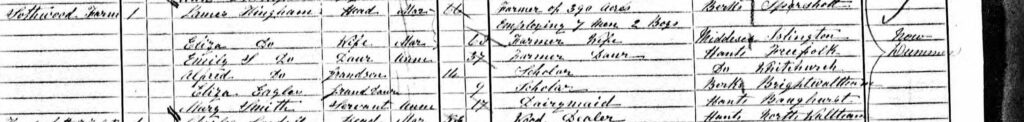

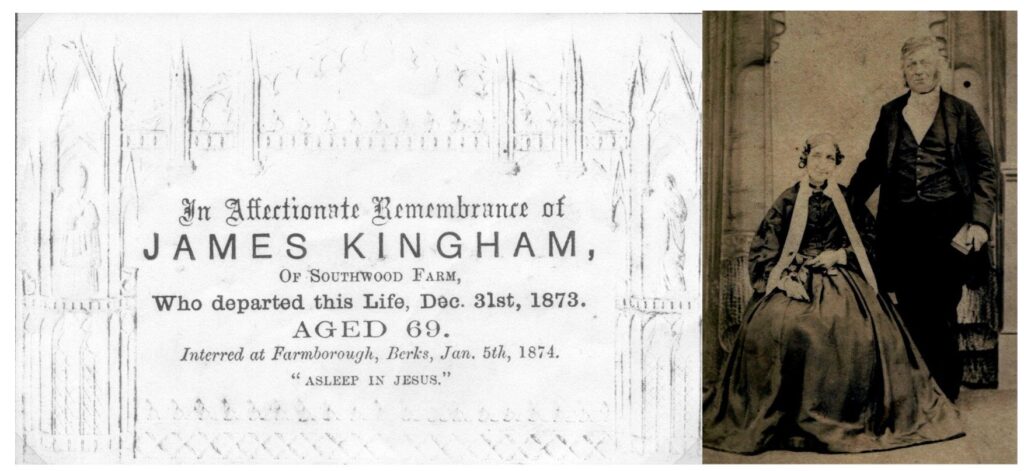

I have an affection for old Downsie, not least because I have a family connection with him in that a quarter of a century after the Downs family left Southwood Farm, a 4x great uncle of mine, James Kingham (1804-1873) and his wife, Eliza, took on the same farm. Indeed, they both died there. Two memorial cards that have survived in the family archives mention the farm, and so does the inscription on the couple’s grave. The 1871 census shows that the Kinghams farmed what was then 390 acres with the help of seven men and two boys. Among the household was a dairymaid, so by then the farm certainly had livestock.

The 1871 census for Southwood Farm, Winslade, Hampshire

The memorial card and James and Eliza Kingham

It means something special to me that forebears of mine had an intimate relationship with the same landscape Downsie grew up in. It was, after all, where Downsie learned to be a gardener. At different times, the Downs family and the Kinghams lived in the same farmhouse and farmed the same fields.

Please send any feedback to contact@stuarteagles.co.uk