Few people can rival Robert Hewison in the variety of his achievements. As a historian of post-war Britain he has interpreted, analysed and explained the cultural life of a nation to which he has made his own extraordinary contribution. As a broadcaster on the BBC, as a performer and historian of comedy, as a theatre critic for the Sunday Times, as a board member of the National Student Drama Festival, through his academic posts, his work with think-tanks, and in numerous other collaborations, he has been a vital influence on the lives of so many.

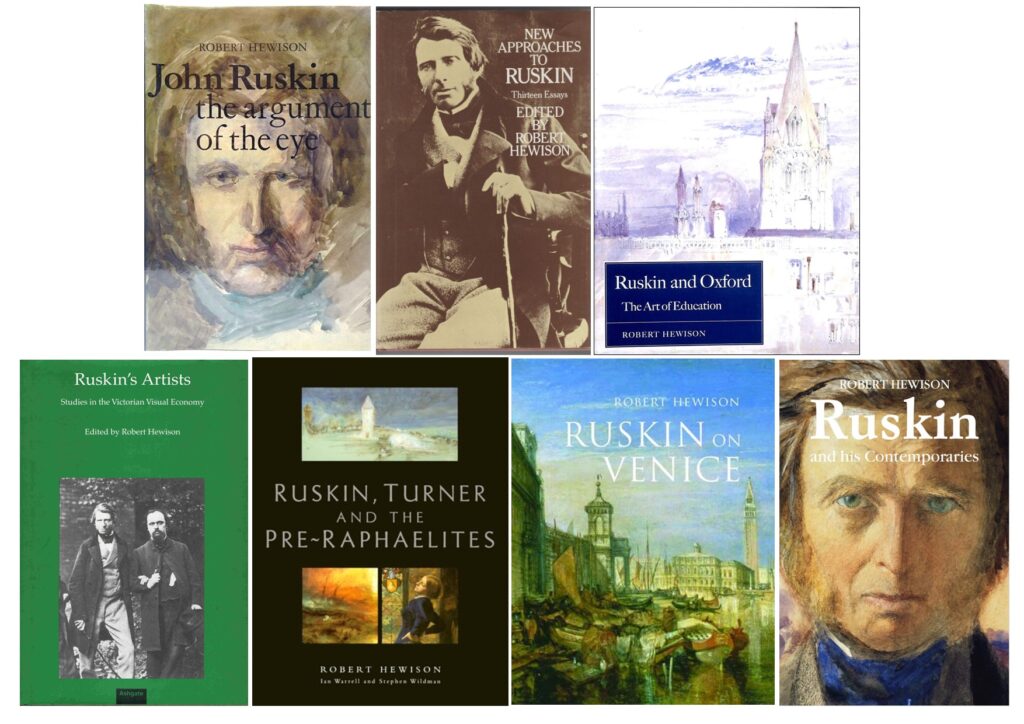

His great intellectual passion for the Victorian critic of art and society, John Ruskin, has fostered exemplary scholarship. His interest in Ruskin in the 1960s led him to dramatise the Ruskin vs Whistler trial for television and to participate in the foundational academic conference at Brantwood in 1969. Over a period of more than 50 years he has explored Ruskin’s life, work, and legacies in a broad range of books, essays, lectures, seminars, exhibitions and broadcasts. In 2000 he followed in Ruskin’s footsteps as Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford. In recent years he has chaired Ruskin To-Day, an informal gathering of the people and organisations interested in Ruskin’s ideas.

A few friends in the Ruskin world have come together online to pay tribute to his outstanding contribution to Ruskin Studies and to say,

HAPPY 80TH BIRTHDAY,

ROBERT HEWISON.

Sara Atwood

Robert, your Argument of the Eye was among the first critical works that I read about Ruskin as an undergraduate, and your books have played a meaningful role in my development as a Ruskin scholar during the past twenty years. I was a star-struck PhD student when I heard you lecture for the first time in London in 2001 at the ‘Locating the Victorians’ conference in South Kensington (you spoke on Ruskin and Henry Cole). Although today I am fortunate to know you as a colleague, I remain an admirer; those of us who care about Ruskin owe a debt of gratitude to you for your intelligence, knowledge, generosity, and good humor. Ruskin urged his readers neither “to please, nor displease you; but to provoke you to think” and you have always done so.

Your wide-ranging work as a cultural historian and your engagement with contemporary ideas and debates mean that you are particularly well-suited to make the case for Ruskin’s importance today. You have done so not only in your many important books about Ruskin but as the chair of Ruskin To-Day, which has grown in membership and visibility under your dedicated leadership.

Your work has enriched and inspired my own scholarship, offering me new perspectives and challenging me to think deeply and differently. It is an honor to know you and I am delighted to wish you a very happy 80th birthday. May this day and all those to follow bring you good health and an abundance of “the things that lead to life”.

Stuart Eagles

Sat in a former public toilet in west London which had been conveniently converted into an Italian restaurant, Robert asked me what interested me intellectually beside Ruskin. After listening carefully to my rambling reply he enthused that ‘Dickens, Ruskin and Victorian political economy’ would make a fruitful subject for a dissertation. Such perspicacious synthesis is characteristic of the invaluable guidance he has helpfully and generously provided ever since. His vital critical engagement with my work towards an MA degree, and his constant encouragement, not only saw me across the finishing line, but took me up to Oxford.

I was an undergraduate when I first met Robert and attended the illuminating seminars in Literary Modernism he led at Lancaster University with the energy, passion and flair that are his hallmarks. Each week he appointed a student to summarise the next lecture. Except, of course, the first time. The introductory lecture had been given by Robert himself and he selected me post hoc to give the summary. I managed somehow and we seemed to understand each other from the start. I was always impressed by the detailed, challenging, good-humoured and purposeful one-to-one and face-to-face feedback he gave students on their work.

Robert is an original thinker, a first-rate writer, a consummate lecturer, a dedicated teacher and an outstanding Ruskin scholar. From the critical insights of The Argument of the Eye to the meticulous and comprehensive analysis of Ruskin on Venice, and in numerous essays, exhibitions and broadcast interviews, Robert has explained with exemplary lucidity Ruskin’s heritage, motivations, ideas, art, religion, politics, projects, legacies and limitations in terms of people, places and institutions.

I owe him a debt of gratitude greater than I can describe. It is a privilege to call him my friend and an honour to wish him a very happy 80th birthday.

Mark Frost

Robert, your work has been immensely significant to me, as it has been to so many others, and to the various fields to which you have so ably contributed for many decades. We owe a considerable debt to you, first of all, as one of those to rescue, rehabilitate, and restore Ruskin Studies after a long period of quietude. My own encounters with you during the days of the Ruskin Seminar at Lancaster University were deeply helpful. The Argument of the Eye was one of the books that helped shape and determine my path into studies of Ruskin and environment, and its wisdom and sympathy helped me to see Ruskin more clearly and to progress, as did your admonitions on the weaknesses of an early MRes draft. You brought immense ability to your studies of Venice, and your work on Ruskin and Sheffield was important in my own subsequent Guild studies – and your support for that work was much appreciated. The prolific nature of your researches are matched only by their quality. I’m sure that you will receive many heartfelt tributes on your eightieth birthday, but I wanted to make sure mine was amongst them. Happy birthday.

Cynthia Gamble

Dear Robert, I have been privileged to know you through our shared interest in Ruskin and work at Lancaster, and to enjoy so many engaging discussions with one of the most original thinkers and writers of our age. Congratulations and best wishes.

Gabriel Meyer

Robert Hewison’s The Argument of the Eye (1976) was one of the first books I read about Ruskin.I have been grateful for this blessing ever since. By then, twenty-five years ago, there were dozens of studies available to inform or bewilder the newcomer to Ruskin. What I found in Robert’s study was an orientation to the whole of Ruskin – namely, that Ruskin’s work, in all its myriad forms, constitutes, first and last, a search for what it means to see.

“. . . Perception does not depend on the eye alone, and Ruskin, speaking in nineteenth-century language of the relation between physiology and psychology, stresses that ‘the physical splendour of light and colour, so far from being the perception of mechanical force by a mechanical instrument, is an entirely spiritual consciousness, accurately and absolutely proportioned to the purity of the moral nature, and to the force of its natural and wise affections.’ Mind and eye work together . . .” The Argument of the Eye, pg. 211

Confronted with 39 volumes in the Library Edition of Ruskin’s Works and a bewildering array of genres, such insights are worth their weight in gold. In addition, Robert’s judicious temperament, his profound good sense, on full display in his writings on Ruskin, made one trust him. Many early accounts of Ruskin, understandably, were written by partisans, wielding the pen against indifference, defending the Master’s reputation against often-careless speculations. While Robert ably argued the case for Ruskin’s importance, he has never failed, in a long and productive career, to let Ruskin be Ruskin – Ruskin, unedited, as he is, with rough edges and quirks as well as towering insights – insights, he notes, that were part of a process, always alive, always evolving.

These impressions, fed by years of reading Hewison’s shelf of Ruskin studies (on Venice, Turner, Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelites, Giotto, Ruskin at Oxford,Ruskin’s contemporaries, etc.) were both confirmed and enriched by coming to know Robert personally over the past few years. Robert delivered our Ruskin Art Club “Ruskin” Lecture in the bicentennial year, 2019 (cf. our YouTube channel, www.ruskinartclub.org), and the two of us got to know each other tooling about Los Angeles, visiting libraries and galleries, and treating ourselves to nonstop conversations about Ruskin for several memorable days. More recently, Robert and his wife Erica hosted me and my research assistant during a stay in the UK in 2022, where the round of breakfasts, leisurely dinners and Ruskin continued.

Cheers and blessings, Robert, on your birthday, and to the wealth that is Life with “all its powers of love, of joy, and of admiration.”

Kay Walter

Robert Hewison is a professional rather than a personal acquaintance, but I persist in calling him “friend” because of his contributions to fellow Companions of the Guild of St George, my students, and other learners far and near. He is generous with his accumulated knowledge to sophisticated and developing scholars alike.

As a child, when I read a book I truly enjoyed, I would tear through it voraciously chapter by chapter until I sensed the end nearing. Then, I would peek through the remaining pages, measure them carefully, and slow my pace to a crawl. I would pause among paragraphs, dawdle over words, linger among lines, deliberately unmark my place so that I needed to back up and read again. Dread grew heavier as the pages-to-go grew lighter in my hand. If I loved the story, I hated to find its end.

Hewison renews in me that childhood anguish. When I encountered his audio recording of selections from The Stones of Venice, I was mesmerized and spent my days binge-listening to the first dozen or more episodes. As I realized their number was finite, I kept finding reasons to interrupt my trance, back up, and put off the final words. Listening was a rich experience that I wanted to endure.

Reading his recent book, Ruskin and his Companions, was similarly delightful. Every part seems an invitation to think of Ruskin in new ways, form new connections to my teachings, and see my own life in a new light.

It doesn’t surprise me so much that Hewison is turning 80, only that he’s actually mortal. What human could accomplish all he has in such a short time? I wish my friend the very happiest birthday so far, many happier ones to come, and an audience worthy of his wisdom.

Michael Wheeler

When I first set out in pursuit of what became the Ruskin Project at Lancaster University (establishing the research centre, building the Library and creating the Foundation that would also care for Brantwood), I knew that my second port of call after Jim Dearden had to be Robert Hewison. Robert could not have been kinder. Having been a leading player in the Ruskin revival over the previous couple of decades, Robert was happy to share his impressions of people and places in Britain and overseas, to offer guidance concerning next steps in Lancaster’s project, including on the elephant traps, and to promise support in the coming months and years. This support was forthcoming: he was always willing to talk by phone or face-to-face as the inevitable complications arose. I was delighted when Robert accepted our invitation to be a professor at Lancaster and to become one of the most dynamic and influential trustees of the Ruskin Foundation. He played a leading role in supporting the work of the research group at the university, holding forth with his customary energy in the bar after seminars. Always brilliant, never shy, Robert enthuses about Ruskin, explains his principles and contributes so much to scholarship relating to his work. Consider, for example, his major publications on the Argument of the Eye, on Oxford and on Venice. Can we believe that the man whose youthful energy has inspired us for so many years is turning 80? Facts is facts, however, so let us offer Robert many congratulations and many happy returns of the day.

Stephen Wildman

Robert’s name has become as synonymous with Ruskin studies as those of James Dearden and Van Akin Burd. Having met only briefly before, I was pleased to encounter him at Lancaster University within weeks of beginning my Curatorship of the Ruskin Library in October 1996, attending Clive Wilmer’s lecture on ‘Ruskin, Morris and Medievalism’, the second Mikimoto Memorial Ruskin Lecture. Robert had given the last of the original Ruskin Lectures in 1994, on ‘“Paradise Lost”: Ruskin and Science’.

It was heartening to have as one of its great supporters a scholar who recognised the importance of drawings for a proper understanding of Ruskin, just as John Howard Whitehouse had envisaged. Beginning with John Ruskin: The Argument of the Eye (1976), one of the seminal books in modern Ruskin studies, Robert highlighted this in the exhibition Ruskin and Venice (1978), later editing Ruskin’s Artists: Studies in the Victorian Visual Economy (2000), several of whose contributions derived from Ruskin Seminars at Lancaster, where he was a Visiting Professor in the English Department. Robert’s presence invariably enlivened the Seminars (both during and afterwards, latterly at Greaves Park), as they did the less enjoyable and very much less fruitful meetings of the Ruskin Foundation, for which he acted as a University appointed Trustee.

It was a pleasure to be involved with the centenary exhibition at the Tate in 2000, Ruskin, Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites, along with Robert, Ian Warrell, and the architect of the Ruskin Library, Richard MacCormac. There was no more dedicated user of the Library and the Whitehouse Collection, and it was a joy to see the ever-growing pile of record cards, pencilled in his elegant flowing hand, which were to underpin the meticulous scholarship evident in Ruskin and Venice: The ‘Paradise of Cities’ (Yale 2009). Never before can the Venetian Notebooks have been so carefully studied and put to similarly resounding use.