In the first of a new pair of Ruskin Research Blogs, Stuart Eagles begins to explore how Ruskin helped to inspire the Garden City Movement. He starts by looking at the movement’s founder, Ebenezer Howard.

RUSKIN & THE GARDEN CITY MOVEMENT:

I. EBENEZER HOWARD & THE FOUNDING GOSPEL

In “The Mystery of Life and Its Arts”, a lecture delivered on 13 May 1868 in Dublin, Ruskin said that “whatever our station in life”:

“those of us who mean to fulfil our duty ought first to live on as little as we can; and, secondly, to do all the wholesome work […] we can, and to spend all we can spare in doing all the sure good we can.

“And sure good is, first in feeding people, then in dressing people, then in lodging people, and lastly in rightly pleasing people, with arts, or sciences, or any other subject of thought.”

(The Works of John Ruskin (in 39 vols), eds. E.T. Cook & A. O. Wedderburn, 18:182)

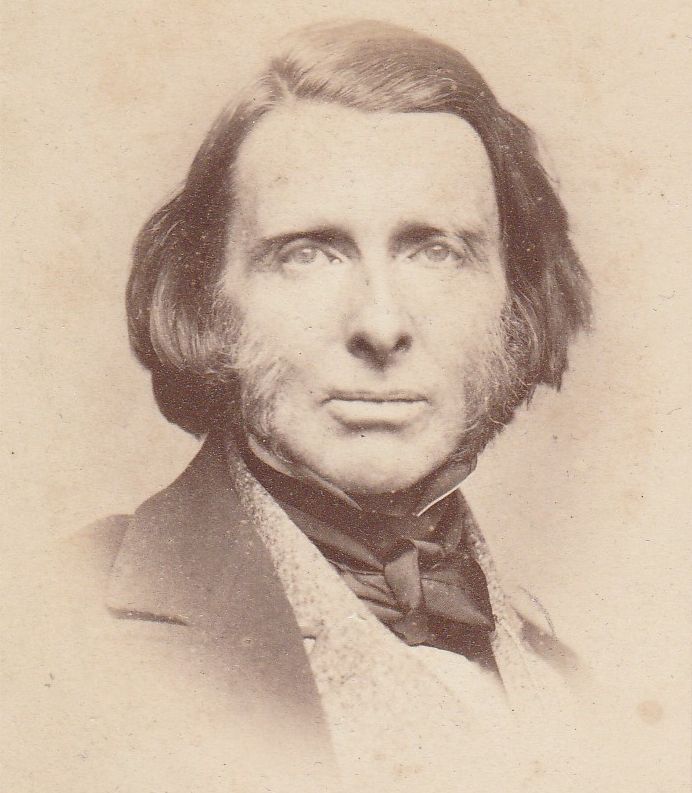

John Ruskin

John Ruskin

This blog—the first of a pair—is concerned principally with the “sure good” of “lodging people”. Whilst some attempt has been made to place this Ruskinian duty in its broader social and political context, we will for now leave aside Ruskin’s important support for Octavia Hill’s model housing scheme in London and return to it in a future blog. Here, we will explore Ruskin’s influence on the development of an experiment which began in Britain in the first decade of the twentieth century. It was called the Garden City Movement. Its aim was to plan and build communities which would preserve and combine the best qualities of town and country, of urban and rural life. The scheme was given practical expression in the Hertfordshire countryside with the founding of Letchworth (from 1904) and Welwyn (from 1920).

The Garden City Movement arose from a recognition of the mounting difficulties Britain faced in the late nineteenth century. Agricultural depression had pushed more and more people off the land and out of the villages to seek industrial and commercial work in the increasingly overcrowded towns and cities.

The movement was rooted in the widespread concern about the effect and manifold consequences of urban squalor. The problem was regarded as particularly acute in London’s East End. The sense that something had to be done to address this dangerously unhealthy and unjust situation was voiced most consequentially in the Congregationalist pamphlet, The Bitter Cry of Outcast London (1883) written by the Rev. Andrew Mearns, and publicized with characteristic zeal by the campaigning journalist and newspaper editor, W. T. Stead.

The Garden City ideal was the brainchild of Ebenezer Howard (1850-1928), himself a lifelong Congregationalist. He had been a Parliamentary shorthand reporter, had followed first-hand many of the political debates about the problems of contemporary society, and had got to know many influential people. He regularly took part in the discussions held in London’s debating societies. He had also spent time living in — and even trying to farm — the more plentiful acres available in the United States, an experience that underlined to him the virtue of space and the value of the land.

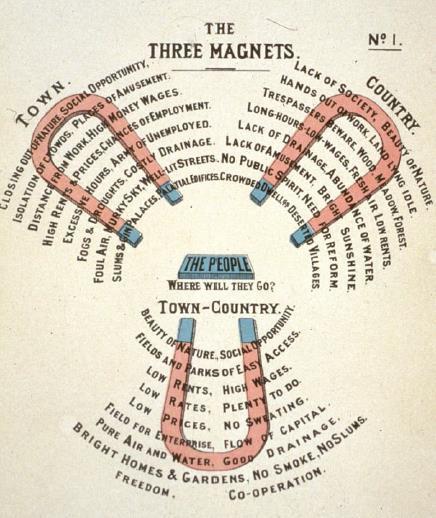

Howard visualized his Garden City plan in a striking word diagram, “The Three Magnets”. It shows how the Garden City, by attracting the best qualities of town and country, could also repel their worst aspects. This re-balancing would address contemporary problems. And it promised hope for a better future. Inevitably, there were many sceptics, but the evangelists of the Garden City Gospel prophesied the New Jerusalem.

Ebenezer Howard, “The Three Magnets”

Howard’s utopian vision was of a community or settlement characterized by natural beauty and social opportunity, where fields and parks would be easily accessible; rents, rates and prices would be low; wages would be high, places of work would be located nearby, and there would be no sweated labour; residents would live in a smokeless atmosphere where the air and water were pure, there was proper sanitation and drainage, and slums had been replaced by bright homes and gardens. It would be a land of freedom and co-operation.

So, he proposed an experimental scheme. He translated his vision into a practical plan to which he gave full expression in his book, Tomorrow, A Peaceful Path to Real Reform (1898). As the title suggests, it makes the business case for garden cities in sober but persuasive, ambitious though achievable, and determined yet diplomatic terms.

Although Howard took inspirational quotes from many texts and authors, it is notable that among the sources he cited at the head of the first chapter (p. 12) was Ruskin and Unto this Last.

“No scene is continuously and untiringly loved but one rich by joyful human labour, smooth in field, fair in garden, full in orchard, trim, sweet, and frequent in homestead, ringing with voices of vivid existence. No air is sweet that is silent; it is only sweet when full of low currents of undersound — triplets of birds, and murmur and chirp of insects, and deep-toned words of men, and wayward trebles of childhood. As the art of life is learned, it will be found at last that all lovely things are also necessary — the wild flower by the wayside as well as the tended corn, and the wild birds and creatures of the forest as well as the tended cattle, because man doth not live by bread only, but also by the desert manna, by every wondrous word and unknowable work of God.” (Original: Ruskin, Works, 17:111)

(Howard altered Ruskin’s punctuation in a minor way — mostly by replacing semi-colons with commas — and made a few other changes: Ruskin wrote “continually” not “continuously” and he gave “undersound” as two words rather than one.)

The quote, from the fourth and final essay of Unto this Last, “Ad Valorem”, thus ends with a fusion of Biblical verses paraphrased from Deuteronomy viii.3 and Matthew iv.4. Ruskin articulates a Christian vision of the sacred city, which promoted harmony with the natural world — beautiful, peaceful, and fruitful, as Ruskin wrote in a different context elsewhere. It gives poetic expression to Howard’s magnetic image of a garden city where “beauty of nature” and “social opportunity” would abound.

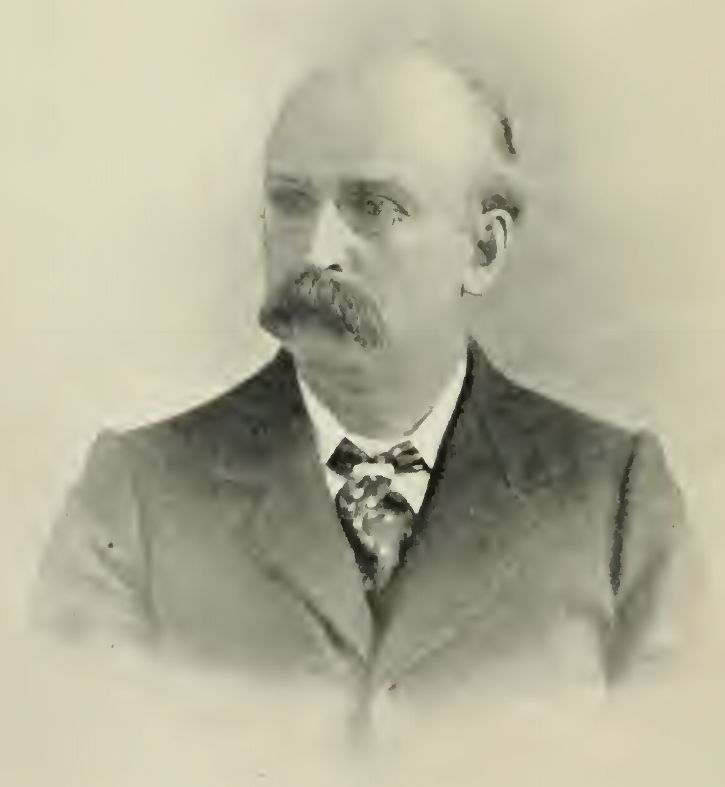

Ebenezer Howard (1902)

Ebenezer Howard (1902)

When Howard reissued his book, under the title, Garden Cities of To-morrow (1902) he replaced the quote from Unto this Last with one taken from the same lecture with which this blog began, namely “The Mystery of Life and Its Arts”.

“[T]horough sanitary and remedial action in the houses that we have; and then the building of more, strongly, beautifully, and in groups of limited extent, kept in proportion to their streams, and walled round, so that there may be no festering and wretched suburb anywhere, but clean and busy street within, and the open country without, with a belt of beautiful garden and orchard round the walls, so that from any part of the city perfectly fresh air and grass, and sight of far horizon, might be reachable in a few minutes’ walk. This the final aim.”

(Qtd in Howard, p. 20; original, which was first published in the revised second edition of Sesame and Lilies, can be found in Ruskin, Works, 18:183-184.)

It is not difficult to comprehend why Howard thought this more practical expression of the purpose of housing and homely life chimed more obviously with a plan beginning to take practical shape.

Ruskin’s vision of the ideal city drew heavily on notions of the idyllic country village and a folk memory of rural life in medieval England. Yet, in his plan for the garden city Howard had devised a scheme to make a modern reality of something strikingly like it. There are many points of comparison in the wording of this quote from Ruskin and Howard’s magnetic word-diagram. We might like, with more or less justification, to find in Ruskin’s words anticipation and commendation of what we now call the green belt. However far we like to go, or however carefully we resist it, the affinities between Ruskin’s vision and Howard’s plan are palpable. Both drew on the past, not to revive it, but to revitalize the present with a vision of the future which was both utopian (in the sense of being attractively idealistic) yet realistically attainable.

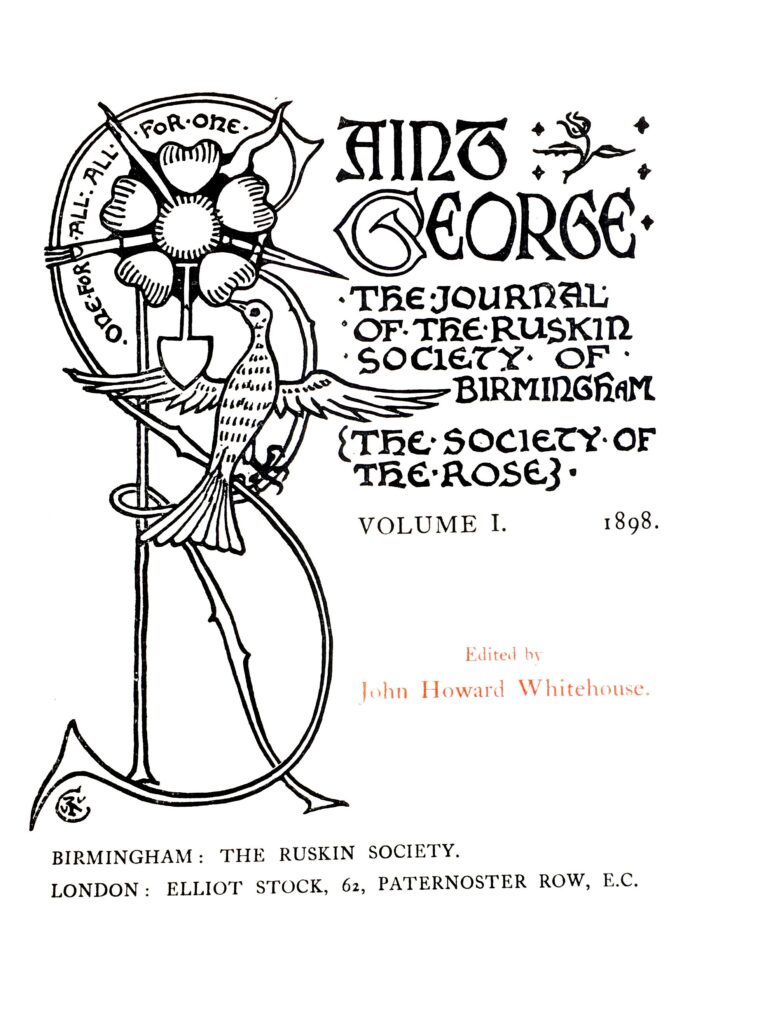

In July 1904, just before Letchworth was to welcome its first residents, Howard wrote an article on “Our First Garden City” in Saint George, the progressive journal of the Ruskin Society of Birmingham. It might have formed the basis for a lecture on “Social Individualism in Theory and Practice” that he went on to give in December of the same year at the Dudley Gallery of the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly to members and guests of the Ruskin Union, a sort of umbrella organisation that sought to bring together the different Ruskin societies around the United Kingdom. Article and lecture suggest a level of engagement with Ruskinians which is itself instructive, though Howard was indefatigable as a spokesman and it is certainly true that he addressed a broad range of groups, far and wide.

The cover of the first issue of

The cover of the first issue of

Saint George (1898)

(Unless otherwise stated, subsequent quotes are from Ebenezer Howard, “Our First Garden City” in Saint George, vol. 7, no. 27 (July 1904), pp. 170-188, only the relevant page number is given.)

Unsurprisingly, given the nature of the journal in which his article was published, Howard once again quotes from Ruskin at the head of his contribution. Interestingly, he chose to return to Unto this Last, but this time selected from the first of its essays, “The Roots of Honour”.

“Observe, the merchant’s function (or manufacturer’s, for in the broad sense in which it is here used the word must be understood to include both) is to provide for the nation. It is no more his function to get profit for himself out of that provision than it is a clergyman’s function to get his stipend. This stipend is a due and necessary adjunct, but not the object of his life, if he be a true clergyman, any more than his fee (or honorarium) is the object of life to a true physician. Neither is his fee the object of life to a true merchant. All three, if true men, have a work to be done irrespective of fee — to be done even at any cost, or for quite the contrary of fee; the pastor’s function being to teach, the physician’s to heal, and the merchant’s, as I have said, to provide. That is to say, he has to understand to their very root the qualities of the thing he deals in, and the means of obtaining or producing it; and he has to apply all his sagacity and energy to the producing or obtaining it in perfect state, and distributing it at the cheapest possible price where it is most needed.”

(Qtd in Howard, p. 170; original in Ruskin, Works, 17:40.)

Ruskin’s unwavering sense of Christian service and duty underlines the obligation to provide; uncomplaining sacrifice was expected wherever it was necessary. Howard used the moral force of this argument in aid of his campaign of expectations management. Moreover, he translated Ruskin’s moral imperative into a practical business proposal: “the investing public of this country might enjoy no inconsiderable share in the delight of gradually bringing about a state of society which will represent a marked advance upon the present”, Howard told readers of Saint George, and “this could be done, not only without loss, but with actual gain to the investors” — though it was a gain which Ruskin among others “urged must not be regarded as the chief end in view — the real end and aim being the supply of human need” (p. 172). Howard was thinking not only of the shareholders in the First Garden City Company, but also of the small-scale manufacturers and other businesses he hoped to attract to Letchworth. It would mean that residents could walk to work rather than commute.

The modest dividend of 5% that Howard envisaged would be paid to stakeholders in the Garden City Company matched the level of return expected by Ruskin on his investment in Octavia Hill’s first housing scheme. It had become the standard percentage associated with philanthropic and ethically sound business. Howard hoped that it would accordingly attract the right kind of investors — that is, investors committed for the long-term, loyal to the principles of the movement, and modest in their expectations of a return. Howard had high but ultimately vain hopes of involving the Co-operative Society.

Moreover, Howard hoped that investors in the Company would demonstrate “the ‘true function’ of a landlord; which, to follow Ruskin’s thought, is to provide the best cottages at the lowest rents; and they may come into closer and more friendly association with the workpeople than would otherwise be possible without undue intrusion of themselves” (p. 187). By “undue intrusion”, it is unlikely that Howard was thinking of Octavia Hill’s model army of rent collectors with social welfare at the forefront of their minds. Rather, he had in mind the university men, involved in such university settlements as Toynbee Hall in Whitechapel, who lived among the poor dwelling in the city slums.

Yet, nonetheless, Howard firmly rooted his Garden City ideal in a tradition which included the university settlements (p. 185), industrial villages such as Lever’s Port Sunlight and Cadbury’s Bournville (pp. 177, 188), and philanthropic developments such as that of the Carnegie Trust in Dunfermline (p. 188) to which another Ruskinian town planner — Patrick Geddes — acted as a consultant. It was “their example and influence”, Howard argues, that “prepare[d] the way” to his own plans for a Garden City — and this notion of the way having been prepared, the idea that his scheme was part of a broader reform movement, merited the inclusion of the phrase three times in his article (pp. 182, 183).

Howard was mindful of Saint George’s readership, and appears characteristically alert to the fact that the leading Ruskinian, John Howard Whitehouse (1873-1955) was the journal’s editor. Whitehouse was then working at Dunfermline for the Carnegie Trust, had formerly worked at Bournville for Cadbury’s, and would in fact go on to work at two university settlements — one in Ancoats, Manchester, the other at Toynbee Hall.

Howard also quoted approval of his plan from the famous English writer, H. Rider Haggard. Nevertheless, we should also recall the dismissive attitude of George Orwell, who wrote in The Road to Wigan Pier (1936), of how communism and socialism draws to it — like a magnet, so to speak — “every fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal-wearer, sex-maniac, Quaker, ‘Nature-Cure’ quack, pacifist, and feminist in England” and proceeded to describe in unflattering terms his observations of Letchworth as it had developed nearly a decade after Howard’s death.

In the next blog, we will look at the men tasked with making a reality of the Garden City ideal on the ground: Raymond Unwin and Barry Parker. In different ways, they too had been influenced by Ruskin’s writing and ideas.

The first of the quotes Howard took from Ruskin, in which Ruskin celebrated the virtues of the simple life with “the wild flower by the wayside as well as the tended corn, and the wild birds and creatures of the forest as well as the tended cattle” was foreshadowed in an earlier passage of Ruskin’s writing. It occurs in the third volume of Modern Painters (1856) and underlines what Ruskin considered truly important and what he did not. Scorning past errors, the thirtysomething Ruskin is hopeful for the future. It is an apt thought on which to end, because part of it was quoted in the conclusion to a speech made by William Percival Westell (1874-1943), the curator of Letchworth Museum. Westell was speaking in May 1914 on what would turn out, of course, to be the eve of the biggest global war humanity had ever seen. Yet he spoke from the scene of the First Garden City experiment. It was an experiment which — whatever he might have made of its details had he lived to see it — would surely have pleased Ruskin in no small measure.

“To watch the corn grow, and the blossoms set; to draw hard breath over ploughshare or spade; to read, to think, to love, to hope, to pray,— these are the things that make men happy; they have always had the power of doing these, they never will have power to do more. The world’s prosperity or adversity depends upon our knowing and teaching these few things: but upon iron, or glass, or electricity, or steam, in no wise.

“And I am Utopian and enthusiastic enough to believe, that the time will come when the world will discover this. It has now made its experiments in every possible direction but the right one: and it seems that it must, at last, try the right one, in a mathematical necessity. It has tried fighting, and preaching, and fasting, buying and selling, pomp and parsimony, pride and humiliation, — every possible manner of existence in which it could conjecture there was any happiness or dignity: and all the while, as it bought, sold, and fought, and fasted, and wearied itself with policies, and ambitions, and self-denials, God had placed its real happiness in the keeping of the little mosses of the wayside, and of the clouds of the firmament.”

(Ruskin, Works 5:382-383)

Please send any feedback to contact@stuarteagles.co.uk