In the previous Ruskin Research Blog Stuart Eagles explored how Ruskin helped to inspire the Garden City Movement. In this second and final part, he focuses on the Ruskinian credentials of the men tasked with planning and designing Letchworth, Raymond Unwin and Barry Parker. It is dedicated to the memory of the great Ruskin scholar, Francis O’Gorman (1967-2024), a kind, gentle and fiercely intelligent man taken from us far too young.

RUSKIN AND THE GARDEN CITY MOVEMENT:

II. UNWIN AND PARKER, DESIGNING UTOPIA

The architecture and design partnership between Raymond Unwin and Barry Parker won the competition to plan the First Garden City at Letchworth. Developing Ebenezer Howard’s ideals into a practical scheme at the start of the twentieth century, they made a reality of the Garden City in the Hertfordshire countryside. They laid the foundations on which scores of new cities, designed to balance work-life and leisure, and incorporate the benefits of of both town and country, would be built across the globe in the decades that followed. Unwin and Parker’s influence has been both broad and deep, and the influences upon them were likewise many and varied.

The inspiration of John Ruskin and William Morris in Unwin and Parker’s partnership was quickly recognised and acknowledged. The sympathetic socialist newspaper, Clarion, noted in February 1901 how these “good artists in architecture” had already exhibited “some degree for quaint, refined, beautiful, comfortable, and useful interiors of houses, such as the poor working Clarionette student of Ruskin and William Morris longs for” (Clarion, 23 February 1901).

The purpose of this blog is to tease out the extent and character of their Ruskinian connections. Whilst many of these will be familiar to students of their lives and work, the blog will also point to links that have rarely, if ever, been explored before now.

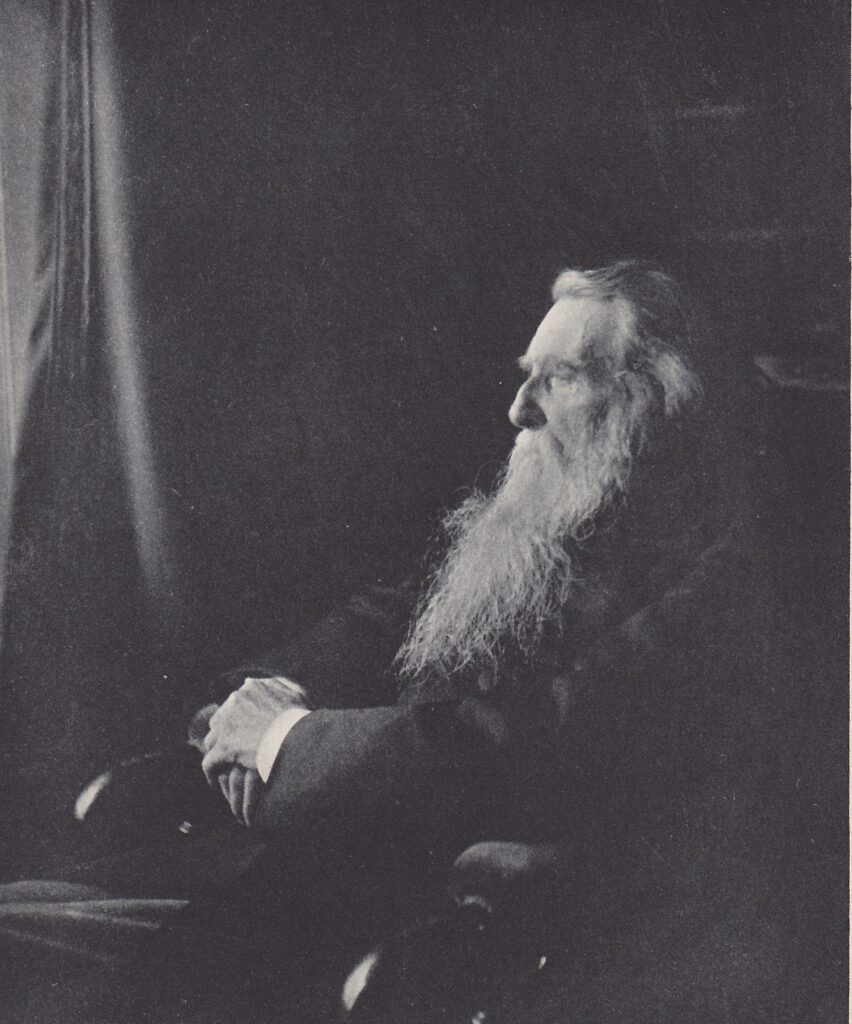

John Ruskin

John Ruskin

RAYMOND UNWIN

On accepting the award of the prestigious Gold Medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1937, Sir Raymond Unwin (1863-1940) said:

“One who was privileged to hear the beautiful voice of John Ruskin declaiming against the disorder and degradation resulting from the laissez-faire theories of life; to know William Morris and his work; and to imbibe in his impressionable years the thoughts and writings of men like James Hinton and Edward Carpenter, could hardly fail to follow after the ideals of a more ordered form of society, and a better planned environment for it, than that which he saw around him in the ’seventies and ’eighties of [the] last century.” (RIBA Journal (April 1937) p. 582)

Raymond Unwin was born in Rotherham, Yorkshire. His father, William, a native of Sheffield who had run a small business as a currier and leather cutter, matriculated at Oxford University at the age of 48 in 1875 and moved his family to the soured city. William became part of the progressive community at Balliol College which had contributed the lion’s share of the undergraduates persuaded to expend their physical efforts not in sport but in Ruskin’s experimental scheme at North Hinksey to improve a neglected patch of rural England. Unwin appeared personally to recall, in the notes for one of his lectures, how Ruskin led “the Hinksey diggers to make a new road”, and the young Raymond may possibly have watched the last of the diggers at work. (Incidentally, Unwin and Parker later designed the vicarage at Thornthwaite, Crosthwaite, occupied by Rev. Hardwicke Rawnsley, another Ruskinian, and one of the diggers at Hinksey; both men were supportive of the work of Rawnsley’s Ruskinian School of Industrial Art in Keswick).

In his inaugural lecture as President of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1931, Unwin praised “the musical voice” of Ruskin and “the more robust and constructive personality of William Morris, and his crusade for the restoration of beauty in daily life” as seminal influences on him in his youth. He went on to suggest that volunteers should come together to clear the slums: “we may yet be called on to provide a leader who, taking a lesson from Ruskin and his Oxford road-makers will gather round him a volunteer band of unemployed architects and operatives, and will lead them in a new crusade to clear and rebuild the slums” (Daily News, 3 November 1931).

Young Raymond certainly heard Ruskin lecture at Oxford, and got to know Arnold Toynbee and Samuel and Henrietta Barnett who were friends of the Unwin family. Unwin was thus directly connected with the key figures in the university settlement movement which was an important part of the broader campaign to improve the lives of the working poor in which Ebenezer Howard rooted his Garden City ideal. It was reputedly Samuel Barnett who persuaded Raymond Unwin to forsake a career in the Church. Instead, Raymond became an engineer’s draughtsman and threw himself into political radicalism. He later fused his socialist fervour and Christian spirituality to embrace the Labour Church. And he would design the Hampstead Garden Suburb for Henrietta Barnett, whose vision both significantly differed from and yet shared in Howard’s own.

(By way of an aside, let us note that Raymond’s brother, William Scully Unwin, heeded neither Ruskin’s message nor the Barnetts’ as a youth: he was a leading rower who was part of Oxford’s victorious team in the University Boat Race of 1885, and later became a clergyman, initially based in Keswick. He later served in Norfolk where he helped found the local—Ruskinian—Council for the Preservation of Rural England.)

The “Ruskinian” path Unwin travelled towards urban planning and social housing is strikingly similar to that of many progressives and reformers in late Victorian Britain who fused Ruskin’s doctrines with Morrisian socialism. This was “Ruskinian” in the sense that they felt themselves inspired by Ruskin, yet it must be admitted that in political and religious matters they often strayed significantly from Ruskin’s own ideas and beliefs.

In the 1880s, this self-conscious “Ruskinism” involved Unwin in membership of the Manchester Socialist Society and then William Morris’s Socialist League—he helped found its Manchester branch, of which he became secretary, and he wrote frequently for its journal, Commonweal. In Manchester, Unwin worked as a draughtsman-fitter at a Manchester cotton-mill, and immersed himself deeply in local discussion groups and campaigning organisations. Among these was the Ancoats Brotherhood, formed in 1889 by the socialist Charles Rowley (1839-1933). Morris was also involved in the Brotherhood’s work, and Unwin sometimes gave talks there. Another figure inspired by Ruskin and Morris involved in the Brotherhood was the philanthropic cotton industrialist, Thomas Coglan Horsfall. Horsfall is a figure to whom we shall return when considering Barry Parker, but it is worth noting here that Unwin not only shared in Horsfall’s enthusiasm for Ruskin and Morris but, at least in part, he later derived from him his own fondness for German models of town-planning which favoured wide, tree-lined streets (a hallmark of the English Garden City), and his belief that the local authority had responsibility for housing and the welfare of the wider community.

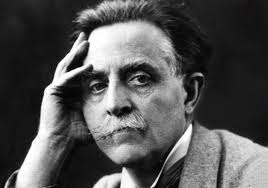

Raymond Unwin

Raymond Unwin

When Unwin lived in Chesterfield and worked for the Staveley Coal and Iron Company he was a frequent visitor to Millthorpe, the rural smallholding and socialist Mecca of his friend, Edward Carpenter. Unwin’s thirst for Ruskin in the 1880s was in fact shared and encouraged by Carpenter. Unwin noted his own reading of Modern Painters and Unto this Last at this time. Parker, too, seems to have read Unto this Last with great sympathy, and both men were familiar with ‘The Nature of Gothic’ in The Stone of Venice, and at least parts of Fors Clavigera.

Unwin was an active member of the Sheffield Socialist Society of which Carpenter was the effective leader. Among its other members were some of the self-style communists who had met Ruskin at his St George’s Museum in Walkley in April 1876 and were involved in his social and agricultural experiment at Totley in rural Derbyshire, near Sheffield and Millthorpe.

Ruskin had wished to see the “thirteen acres” at Totley, which he romantically but inaccurately called Abbeydale, sympathetically cultivated, as far as possible by hand, and he welcomed (at least to begin with) the settlers’ wish to make boots and shoes there. Carpenter was among the later visitors there to lend a hand in the farml work. Among the other radicals Unwin got to know well through the Sheffield Socialist Society were Godfrey Swan, one of the sons of the curators of Ruskin’s museum at Walkley, and John Furniss, whose close friend, George Pearson, himself a socialist, would eventually take on the land at Totley and make a success of it as a family-run market garden.

This finely woven web of Ruskinian connections even extended to the interior decoration of the family home Unwin set up in the 1890s with his Wife, (Fanny) Ethel, a cousin who was the sister of his professional partner, Barry Parker. Their neighbour, the socialist and journalist, Katherine Bruce Glasier (1867-1950), described how the Unwins’ five-bedroomed cottage in Chapel-en-le-Frith in High Peak, Deberbyshire, boasted curtains, blankets and clothes (Mrs Unwin’s dress and their son’s tunic) made from the supposedly hand-woven Laxey flannel made on the Isle of Man at the mill which had been inspired by Ruskin’s ideas and had been founded and managed by a leading Companion of Ruskin’s Guild of St George, Egbert Rydings (see ‘The Passing of Sir Raymond Unwin’, in Labour’s Norther Voice (August 1940) p. 2). Unwin’s broader commitment to the “simple life” was partly inspired by Ruskin’s plea, eloquently expressed in “The Nature of Gothic”, to buy only the products of undivided labour.

Furthermore, Unwin outlined some of its ideas at meetings of Ruskinian organisations, addressing the Ruskin Society of Birmingham on “Town Planning” in November 1907 in which he pointed to the Ruskinian potential of the development at Harborne in the south-west of the city, and he spoke to the Ruskin Union on “Town Planning and Individuality of Towns” in April 1910.

But this is not to suggest either that Ruskin was the most important influence upon Unwin, nor that his view of Ruskin was constantly uncritical. Far from uniquely, the older he got, the more inclined he was to caveat his praise of Ruskin. “When young we all sat at [the] feet of Ruskin, [and] hung upon his musical words”, he noted familiarly in notes he made for a lecture given to the London County Council in February 1930. But he also registered the “[r]eaction against [Ruskin’s] overstatement” and regretted that Ruskin “sometimes did mix up morals and art”. But Unwin endorsed Ruskin’s view that “all most lovely forms and thoughts are taken directly from natural objects” and quoted from Ruskin’s “Lamp of Life’, one of his Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849), in which he wrote

“that things in other respects alike, as in their substance, or uses, or outward forms, are noble or ignoble in proportion to the fulness of the life which either they themselves enjoy, or of whose action they bear the evidence, as sea sands are made beautiful by their bearing the seal of the motion of the water””(Ruskin, Works, 8:190).

Parker and Unwin’s language echoed Ruskin’s overture in Modern Painters to go to nature (see Unwin and Parker, The Art of Building a Home (1901), p. 114).

In November 1885 Unwin wrote to his future wife that the Ruskin ideal was “a very good one in the main though as to his theories of machinery probably we cannot send the clock of time back again”. And he was more than sceptical about Ruskin’s “onslaught onto Democracy, especially in Fors Clavigera”.

Unwin’s attraction to Ruskin’s, admiration for Gothic architecture, and Morris’s bolder development and articulation of it, was clearly expressed in an address, titled “Looking Back and Forth”, given to students at the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1932 (see RIBA Journal (January 1932) p. 205). Unwin extended to the town-planner Ruskin’s view that it was man’s role to serve as custodian of the natural world, and curator of social and aesthetic life.

The influence of Ruskin and Morris undoubtedly contributed to the decision Unwin and Parker took to favour Arts and Crafts-style Garden City cottages, low, angular and cosy, with dormer windows and inglenook fireplaces, with a garden, on a green, and surrounded by fields. At the start of his book, Cottage Plans and Common Sense (1902), Unwin underlined the point by quoting Ruskin’s description of the ideal cottage given in an Oxford lecture published in The Eagle’s Nest (1872).

“[… I]n actual life, let me assure you, in conclusion, the first ‘wisdom of calm,’ is to plan, and resolve to labour for, the comfort and beauty of a home such as, if we could obtain it, we would quit no more. Not a compartment of a model lodging-house, not the number so-and-so of Paradise Row; but a cottage all of our own, with its little garden, its pleasant view, its surrounding fields, its neighbouring stream, its healthy air, and clean kitchen, parlours, and bedrooms” (Ruskin, Works, 22:263, qtd in Raymond Unwin, Cottage Plans and Common Sense (1902). p. 4).

BARRY PARKER

The influence of Ruskin on (Richard) Barry Parker (1867-1947) is less obvious and has gone largely unexamined.

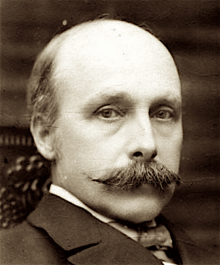

Barry Parker

Barry Parker

Though Parker, whose father was a Derbyshire bank manager, was from a politically conservative background, he came to share the vision for housing and urban planning advanced by Ebenezer Howard and Raymond Unwin, and as the bona fide architect of the three, he helped develop the Garden City Movement into two living communities at Letchworth and Welwyn.

Parker’s Ruskinian connections are generally more obscure and opaque than Unwin’s. He certainly quoted from Ruskin, as he did in a lecture to a group of architects in 1895, when he cited Ruskin’s The Two Paths (1859) in addressing the matter of artistic and architectural integrity:

“You may like making money exceedingly; but if it come to a fair question, whether you are to make five hundred pounds less by this business, or to spoil your building, and you choose to spoil your building, there’s an end of you. So you may be as thirsty for fame as a cricket is for cream; but, if it come to a fair question, whether you are to please the mob, or do the thing as you know it ought to be done; and you can’t do both, and choose to please the mob,—it’s all over with you;— there’s no hope for you; nothing that you can do will ever be worth a man’s glance as he passes by.” (Barry Parker, “The Smaller Middle Class House” in Unwin and Parker, The Art of Building a Home (1901) p. 11, qtd from Ruskin, Works, 16:370.)

There are two under-explored but suggestive Ruskinian connections in Parker’s biography which are worthy of note.

The first of these is Parker’s schooling at Sheffield’s Wesley College. Born in Chesterfield in 1867, the formative part of his education fell in a period when Wesley College was headed by the influential evolutionary biologist, Rev. Dr William Henry Dallinger (1839-1909). Dallinger was a keen Ruskinian who owned a large collection of Ruskin’s writings. In the early 1880s he served as the President of the Ruskin Society of Sheffield. When he gave a lecture in Oxford he met and conversed with Ruskin. Referring sniffily to Dallinger’s important microscopical observations of a unicellular organism, Ruskin said in his Slade lecture, “The Art of England”, that “we saw the whole Ashmolean Society held in a trance of rapture by the inexplicable decoration of the posteriors of a flea” (Ruskin, Works, 33:354). Notwithstanding, Dallinger’s respect and regard for Ruskin was undiminished. It is difficult to imagine that Parker was unaware of all of this. Wesley College was even the custodian of about sixty ambers belonging to the collection of the Guild of St George for which there was no sufficient space at the little museum in Walkley.

The Guild’s collection finally found adequate room for the ambers when the Ruskin Museum opened at Meersbrook Hall in April 1890. A little-known fact is that the interior decoration of the museum’s principal rooms was undertaken by G(eorge) Faulkner Armitage (1849-1937), the Arts and Crafts architect and designer based in Altrincham, Cheshire, under whom Parker was an articled pupil between 1889 and 1892.

The site of Faulkner Armitage’s former studio in Altrincham where

The site of Faulkner Armitage’s former studio in Altrincham where

Parker was a pupil. Photo: Stuart Eagles.

The minutes of the Ruskin Museum Committee reveal that Armitage was personally requested to advise on decoration in September 1889. The fact that he was thus approached is not surprising, given the influence upon him of the ideas of John Ruskin and William Morris. Armitage was in fact the Manchester agent for Morris and Co. The junior trustee of Ruskin’s Guild of St George, and a prominent member of the Ruskin Museum Committee, George Thomson (1843-1921), who was a progressive Huddersfield woollen manufacturer, was certainly familiar with Armitage’s work. He probably got to know him in 1883 when the architect designed a library for a Fine Art Exhibition at Huddersfield, for which Thomson had obligingly loaned him his fine collection of Ruskin books. Thomson would subsequently commission Armitage to decorate his substantial villa, Woodhouse Hall, in Fartown, Huddersfield.

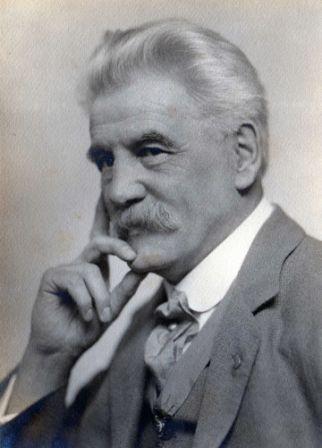

Faulkner Armitage

Faulkner Armitage

Thomson and other members of the committee were probably also aware that Armitage had previously decorated the Art Museum in Ancoats, Manchester, founded by T. C. Horsfall, another disciple of Ruskin and Morris and a devotee of the Arts and Crafts whose influence as a town planner on Raymond Unwin we have already noted. Horsfall was inspired to found his museum by the example Ruskin had set in Walkley, and the ideals articulated in Fors Clavigera (1871-1884) in which he had written of the ennobling educational value of a knowledge of beauty in nature and art. In the late 1870s Ruskin and Horsfall corresponded about the latter’s plans to set up a museum for working people in Manchester. Although Ruskin was characteristically sceptical about its possible success, he nevertheless agreed “to help him all I can in the hard task he has set himself, or, if I can’t help, at least to bear witness to the goodness of the seed he has set himself to sow among thorns” (Ruskin, Works, 34:329-334, specifically p. 329). Armitage was the appropriate interior designer for the Ancoats Art Museum for another reason, too. His father, William Armitage, had founded Armitage & Rigby, a well-known firm of cotton manufacturers in Manchester whose first premises had been in Ancoats.

As Armitage’s pupil, Barry Parker worked for him mainly—as the 1891 census attests—in the capacity of “decorator and designer” focusing on wallpapers, carpets, and other interior fittings. Whilst there is no direct evidence of Parker’s personal engagement in the interior design of the Ruskin Museum, this lack of evidence by no means suggests he was not involved. His frequent visits to the family home in Fairfield, Buxton, in the High Peak of Derbyshire, would certainly have commended his involvement, and it is inconceivable that he was not aware of the work, given his previous connections with Sheffield and the fact that he was part of a relatively small tea.

Given how little has been written about the work on the Ruskin Museum, it is worth pausing to examine some primary sources. The precise details of Armitage’s response to the Ruskin Museum Committee was not recorded, but it was received within two weeks and was sufficiently attractive for the Ruskin Museum Committee to invite him to submit a design proposal with a maximum costing of £200. Particulars of the committee’s requirements were drawn up by Elijah Howarth (1853-1938), the curator at Sheffield’s Weston Park Museum and Howarth subsequently submitted a report with recommendations to improve lighting at the museum.

Having submitted plans for arrangement, fittings, furniture and decoration, Armitage attended a meeting of the committee on 24 October 1889. He was commissioned to carry out the work, pending the submission of specifications and estimates. In December the work was entrusted to Armitage, and the budget agreed was raised to £503 8s. 6d.

Armitage designed and decorated the Picture Gallery, Mineral Room and Library of the Ruskin Museum and so helped to make it, in the words of the Sheffield Daily Telegraph on the day the museum opened (15 April 1890), “a shell quite worthy of the pearl within it”. The Picture Gallery was described as “a well-lighted apartment, chastely decorated in soft and harmonious tints. As in the other public rooms a number of appropriate sentences from the works of Mr Ruskin have been painted on a broad band below the cornice. Here the student is reminded that ‘All things are noble in proportion to their fulness of life’, and that ‘All [great] art is praise’.”

The Mineral Room was also judged to have been “artistically decorated”. The report went on: “The legends which are cast upon the frieze tell us that ‘Pleasant wonder is no loss of time’, and that ‘Nothing that is great is easy’. Pleasant wonder is, indeed, the sensation awakened by the sight of the handsome oak cabinets laden with crystallised minerals noted either for their beauty or utility.” And of the Library the newspapers reported simply that, “The motto chosen to adorn the wall … runs thus: ‘The right function of every museum is the manifestation of what is lovely in the life of Nature, and herein in the life of man’.”

The Picture Gallery, Mineral Room and Library of the Ruskin Museum.

(NB. Major structural work was carried out in the summer of 1892 by the well-known firm of Messrs. Thomas Fish and Son of Nottingham to install a new raised roof constructed of glass.)

LEGACY

The ideas of Howard, Unwin and Parker on housing and town planning became internationally significance. Their development of living Garden Cities in Hertfordshire provided inspiration and practical models to be emulated. All three were sympathetic to Ruskin, Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement. Some of the Ruskinian connections, such as those with the Ruskin Societies and the Ruskin Museum deserve wider recognition. Unwin, by his later involvement in government administration, helped to spread the Garden City Gospel by shaping national policy. His membership of the Tudor Walters Committee (1918) was especially consequential: its Report set the standard for the planning and design of council housing in Britain for decades to come.

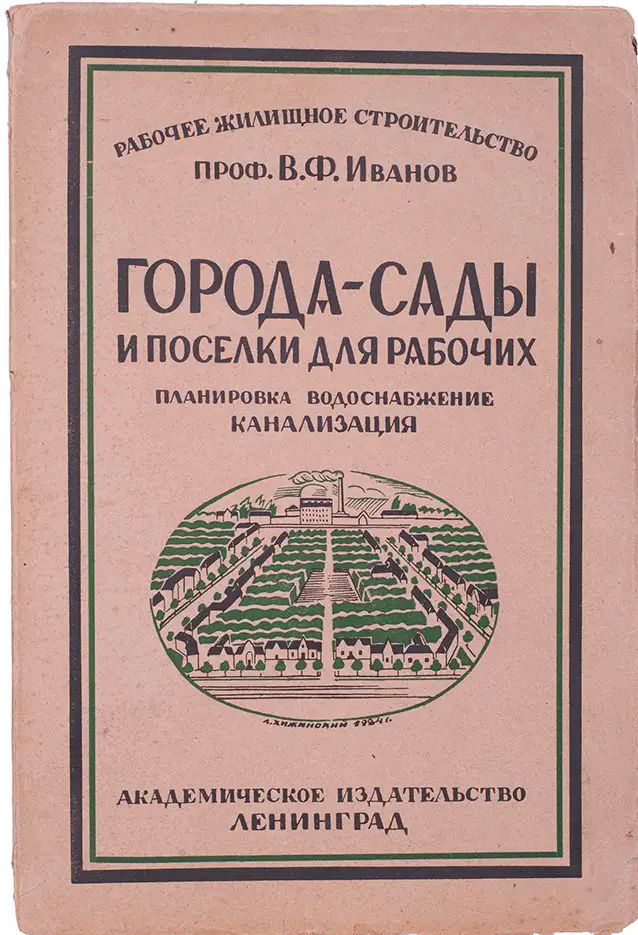

Unwin was also directly involved in spreading Garden City ideals around the globe, particularly through his work as a consultant in the United States. But the ideas were explored in real communities developed in every part of the world, including Africa, Asia and Oceania and South America, as well as throughout Europe, including France, Belgium, Germany, Finland, Czechia, and the Netherlands. The influence also reached Soviet Russia, as illustrated by this pamphlet, Garden Cities and Villages for Workers: Planning, Water Supply, Sewerage, published in Leningrad in 1925.

With thanks to Globus Books, San Francisco

With thanks to Globus Books, San Francisco

for supplying the image

Unwin, in particular, was always acutely aware of the part Ruskin and Morris had played in inspiring him. Speaking in 1924, he neatly summed up that influence. If his point seems so simple as to be obvious, we might then ask ourselves how and why it is that, despite the many attractive and admirable places that have been built around the world in the past century and more, there are yet so many others that have fallen short of our most modest expectations. That there remains much still to do invites us to listen carefully to one of the men who sensitively and sympathetically gave practical expression to a gospel first voiced by John Ruskin, that matchless poet in prose whose ideas should forever resonate and remain relevant.

“The end we are working for, the end that some of the older town-planners like myself, who had the good fortune when they were young men to drink in ideas from the silver speech of Ruskin or the much more vigorous and virile teaching of William Morris, have in mind is that we should build beautiful towns that shall be worth living in and that shall be a pleasure to live in.” (Raymond Unwin, qtd in the Western Mail, 8 May 1924).

Next time, we return to Russia and look at another contributor to the University Settlement and Garden City Movement—a keen Ruskin collector and woollen manufacturer whose family business helped spark a revolution that changed the world…

Please send any feedback to contact@stuarteagles.co.uk