IaIn his latest Ruskin Research Blog, Stuart Eagles reveals the story of the keen Ruskin collector, progressive and philanthropist, Thomas Thornton, whose family woollen business helped spark a revolution that changed the world …

RUSKIN & REVOLUTION:

THE CASE OF THOMAS THORNTON

To Eve Filée

Today’s blog is not so much about revealing one story as making one story out of three. Some of its parts are better known than others, but — as far as I know — nobody has brought all the strands together before now.

Those Ruskin scholars who have heard of Thomas Thornton know something of the man’s interests and background, but not the part his family’s business — the Thornton Woollen Mill Company — played in world politics, and specifically in late imperial Russia. Students of Russian history, on the other hand, and particularly those versed in the makings of the Soviet Union, should be aware of the part that the Thorntons’ enormous textile empire played in the life and career of Vladimir Lenin and the rise of Bolshevism, but they are unlikely to know about any connection with the English polymath, John Ruskin. In the middle are social historians of various turn-of-the-century progressive movements in Britain — university settlements, the Co-Operative Society, the garden city movement — for whom Thomas Thornton is probably but a footnote, not obviously connected to the story of Ruskin’s multiple legacies, let alone to world events.

So, what’s the story? How was a Ruskinian progressive active in British social politics at the turn-of-the-century connected to a revolution that changed the world?

(I) THE RUSKINIANS

Let’s start where you’d expect the Ruskin Research Blog to start — with Ruskin. And, yes, the sub-heading is meant to be Ruskinians (plural) because although Thomas Thornton is the main subject of our interest, other members of the Thornton family were Ruskinians, too.

What little has hitherto been known to Ruskin scholars about Thomas Thornton is confined to what Cook & Wedderburn, the editors of the Library Edition of Ruskin’s Works, have told us. They recorded that Thornton was

“a cloth manufacturer [who was] at one time a resident at Toynbee Hall, [and] had sent a subscription to St George’s Guild. It was he who presented to the National Gallery the bust of Ruskin which stands in one of the Turner Water-Colour rooms.” (Ruskin, Works, 37.484n)

Though this information is useful, so far as it goes — and that isn’t far — it is vague and raises more questions than it answers.

Thomas Thornton (1854-1908), as we shall see, was an intriguing contradiction. His generous philanthropy and political commitments undoubtedly benefited workers in Britain. But the money with which Thornton promoted progressive causes and indulged his Ruskinian passions was derived from a business fortune amassed by his family abroad. He depended entirely on the toil of foreign workers. And those workers were part of a grim history of exploitation that helped to spark a revolution that changed the world.

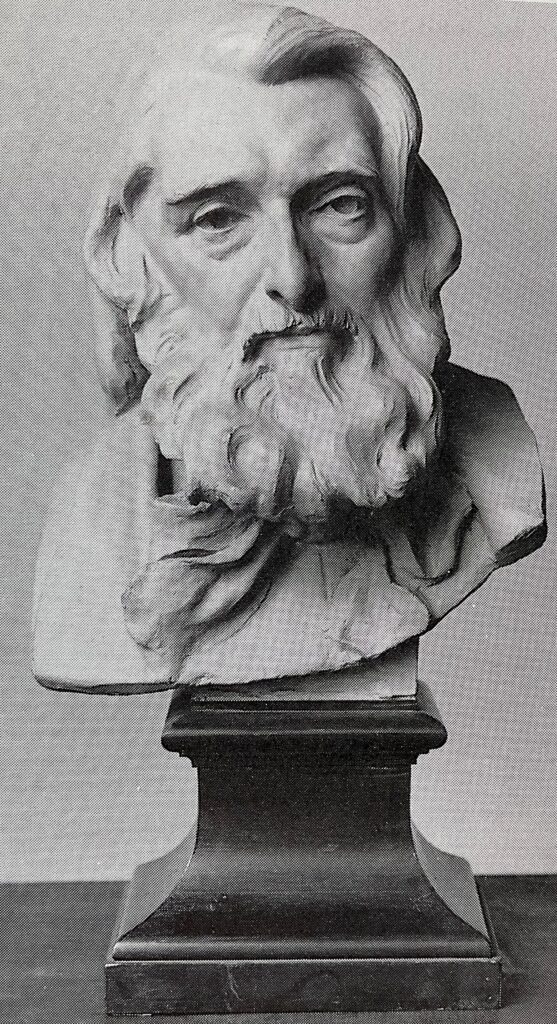

The Ruskin busts by Conrad Dressler, once owned by Thomas Thornton

The Ruskin busts by Conrad Dressler, once owned by Thomas Thornton

The bust mentioned by Cook & Wedderburn was that executed by the English sculptor and potter, Conrad Dressler (1856-1940), in 1884. Now at the Tate, it was presented to the National Gallery by Thornton in 1902. A slightly modified bronze version was donated by Thornton to the Ruskin Memorial Hall at Bournville (see Ruskin, Works, 38.212). Cook & Wedderburn also point out that Thornton’s widow later donated to the British Museum the manuscript of chapter three of the Bible of Amiens (see Ruskin, Works, 38.37

Ruskin Memorial Hall, Bournville © Stuart Eagles

Cook & Wedderburn also reproduced a letter Ruskin sent Thornton in May 1884 in response to a question “about the poor” that Thornton had posed in one of two recent letters. Ruskin told him:

“The most directly necessary charity in England is to save poor girls from distress, overwork, and surrounding evil. Giving definite manual work to young men, or presenting books and other educational material to poor families or public institutions, are both entirely safe and fruitful charities. For the rest, — I have never regretted any manner of charity.” (Ruskin, Works, 37.484).

As this correspondence and the list of donations indicate, Thornton was a philanthropist directly influenced by Ruskin.

It turns out that Cook & Wedderburn only scraped the surface, however, and that a richer, deeper but also darker story lurked beneath.

There is certainly evidence that Thornton and Ruskin corresponded more widely. For instance, the British Library holds a letter from Ruskin to Thornton written in 1882 (British Library: Add.Mss.37951, fo.81: John Ruskin to Thomas Thornton, 1882).

In September 1884, Thornton visited St George’s Museum at Walkley, where Ruskin had deposited his exemplary collection of art-treasures, curated by Henry and Emily Swan for the benefit of the workers and labourers of Great Britain, especially Sheffield’s artisan metalworkers. Thornton’s name appears in the fourth of the surviving museum visitor books. The entry stands out because he gives his address as St Petersburg, Russia.

The Thornton family did have historic Yorkshire connections, however, specifically with Bradford, and there were also business links with Huddersfield, and Thomas Thornton himself frequently visited Britain, especially London and Kent where he had homes. But he spent a lot of time in St Petersburg, where he was born, and worked there for the textile company that had been founded by his grandfather.

We shall return to Russia and Thornton’s Mill presently, but first we should pause to note that Thornton’s association with the Ruskin Collection at Sheffield did not end with his visit in 1884.

In November 1908, following Thornton’s death, the collection — by then housed at the re-branded Ruskin Museum at Meersbrook Hall — was given 460 specimens of minerals, rocks and fossils. The minutes of the Ruskin Museum Committee recorded that the gift came “with [a] catalogue, by Professor Tennant, of London” (23 November 1908). This almost certainly refers to James Tennant (1808-1881), Professor of Mineralogy at King’s College, London. Tennant was also a dealer with premises on The Strand. In the mid-1860s Ruskin purchased from him a few thousand minerals originally in the the Stowe Collection, and continued to make purchases in the 1870s.

At the same time as the minerals were donated, in Thornton’s name, to the Ruskin Museum, a number of other gifts were donated. These included several early volumes of Ruskin’s writings; 44 mounted photographs of art subjects in Venice, Florence and Rome (three of them in oak frames); and a set of plates in portfolio from the magnificent Turner and Ruskin; an exposition of the work of Turner from the writings of Ruskin by Frederick Wedmore (1844-1921), published in two volumes by George Allen in 1900.

As a package, this was a handsome and notable acquisition, but it was added to a few months later, with an entire cabinet full of gold, silver and bronze coins, plus 27 volumes of books on art history, including the index to Fors Clavigera (all noted by the Ruskin Museum Committee on 4 February 1909).

According to Catherine Morley, a diligent historian of the Ruskin Collection, Thornton or his family also “returned” Ruskin’s drawing from a Pier in the Atrium of Lucca Cathedral (1882) which Ruskin had apparently presented to him in 1886 (p. 239). (Morley gives no source or any further details, but the picture is referred to in Ruskin, Works, 33.xlii and 38.264.)

The Thornton bequests, though given in Thomas’s name and evidently taken from his own collection, were made by his widow, Mary Elizabeth Thornton (1858-1942).

Thomas and Mary Thornton were not the only members of the Thornton woollen family associated with Ruskin and the Guild of St George.

In 1910, Miss Frances Thornton (1861-1931), one of Thomas’s cousins who had also been born in Russia, donated to the Ruskin Museum a watercolour study of Tintoretto’s Paradiso, said to have been commissioned by Ruskin himself, though from whom and at what time is not clear (the vague reference is found in the minutes of the Ruskin Museum Committee, 6 October 1910).

The drawing was given in memory of Frances’s sister, Miss Emma Thornton (1864-1909), who was also born in Russia, but mainly grew up in Brighton and later lived at her parents’ English residence at Sunnymead, in Chislehurst, Kent. Emma was a Companion of Ruskin’s Guild of St George. Guild minutes show that she was present at meetings from as early as 4 December 1884, when she was aged 20. Little can be discovered of her involvement, but she organised a reception for Guild Companions at the Grand Hotel in London’s Trafalgar Square, on 7 May 1908. The event was marred by recent bereavements. She was stricken with grief on the death at Bournemouth of her Ruskinian cousin, Thomas Thornton, on 9 April, aged only 53. It had sorely reminded her of the loss of her mother, Elizabeth, only a year before. She was consequently unable to fulfil her role as hostess, but the reception went ahead, and Ruskin’s cousin, Joan Severn, took Emma’s place, and gave a short address, together with the Guild’s then Master, Georges Baker, a blacking manufacturer, and next Master, George Thomson, another wollen manufacturer. The retiring and newly elected Whitelands May Queens were also present, in full dress.

Emma’s health never fully recovered, and she died on 11 February 1909. She predeceased her father, William Lee Thornton (1836-1909) by nine months. On his death, his estate was valued at a colossal £203,763.

Confusingly, Emma Thornton’s name was not entered on the Guild Roll until 1926, following a meeting which authorized the retrospective — and in her case, post-mortem — addition of hitherto unrecorded names of Companions (see Guild minutes, 22 October 1926).

(II) THE PROGRESSIVE

Thomas Thornton was the eldest child of William Lee Thornton’s brother, John Thornton (1823-1874) and his wife, Hannah, née Hughes (1835-1873). His siblings included Sarah, Henry, John, Rebecca, Kate, Charles, and Ernest. Besides his Ruskinian interests and the philanthropy already described, it is not difficult to find public collections which benefitted from his generosity.

But, crucially, Thornton was involved in a range of progressive causes in Britain. He was, as Cook & Wedderburn noted, associated with Toynbee Hall, the first of the university settlements, based in Whitechapel, whose many Ruskinian affinities and connections I have described at length in my 2011 study, After Ruskin: The Social and Political Legacies of a Victorian Prophet, 1870-1920 (Oxford University Press) (see here). Whether Thornton was in fact a “resident” at Toynbee Hall is not clear, but he was certainly listed as an associate in the Annual Report of 1891. One James Thornton, almost certainly a member of Thomas’s wider family, was a resident at Toynbee Hall in 1897.

Thornton’s interests seem to have been broad and varied and included the co-operative movement, the co-partnership movement, and the garden city and garden suburb movements. He also seems to have pursued an amateur enthusiasm for meteorology.

Thornton was a keen enthusiast for co-operative production and a co-partnership model of business ownership and management. This meant that workers owned shares in the business which employed them, from which they received a proportion of the profits by way of a dividend. It also meant that the workers elected representatives to sit on the works’ management committee, giving them a voice in company policy. Most co-partnership businesses provided recreational facilities for their workers, including a canteen and reading room. Such businesses generally paid well, expected less work, and made some paid holiday provision, long before it was a legal requirement for employers to do so.

The most prominent Ruskinian support of co-operative production and co-partnership was George Thomson (1842-1921), the Huddersfield woollen manufacturer present at Emma Thornton’s Guild reception and a man on whom I have written at length in the pamphlet, The Ruskinian Industrialist (2021) (see here). Given Thomson and Thornton’s shared political outlook and common approach to the same line of business (textiles), and the enthusiasm they both felt for Ruskin, it is all but inconceivable that they did not know each other.

Thornton was a member of the Labour Association for Promoting Co-operative Production based on the Co-Partnership of the Workers, founded in the mid-1880s. It is difficult to assess how active he was without further digging, but his membership and financial donations were extended at the turn-of-the-century by his funding of two prizes for essays on the subject of “co-operative production”: the winners received both books and a travel bursary of £12 each.

The prize was connected with scholarships established in the name of Thomas Blandford, who also founded a circulating library which afforded members of co-partnership societies access to exemplary works of literature, science, and art. Most of Thornton’s personal library was donated by his widow to the Thomas Blandford Library. Thornton also served as a Vice-President of the Labour Association. The Yorkshire Factory Times, which called Thornton “one of the pioneers of co-partnership and housing reform” (in Britain, at least), suggested that these travelling scholarships was later extended to workers living in all 14 garden suburbs then in existence (21 August 1913),.

Following Thornton’s death, his widow also gave £500 to the Garden Cities’ Tenants’ Institute, otherwise known as the Co-Partnership Club and Pixmore Institute, in Letchworth, the first of the garden cities discussed in the last two Ruskin Research Blogs. According to the Daily Telegraph & Courier, this generous financial gift funded the building of a new wing, named after Thomas Thornton, as a memorial to his connection with co-partnership (29 September 1911). The new wing, the paper reported, would “provide for the co-partnership tenants at Letchworth means of recreation such as are given by the club houses at Ealing and Hampstead” with an emphasis on reading rooms. The foundation stone was laid on Tuesday, 3 October 1911, and Ebenezer Howard was present at the ceremony alongside Mrs Thornton.

The Thomas Thornton Wing, Letchworth

(III) REVOLUTION

Yet, lurking behind such progressive approaches to industrial relations in Britain, and Thornton’s undoubtable Ruskinian philanthropy, is the darker tale of the family fortune which funded it all.

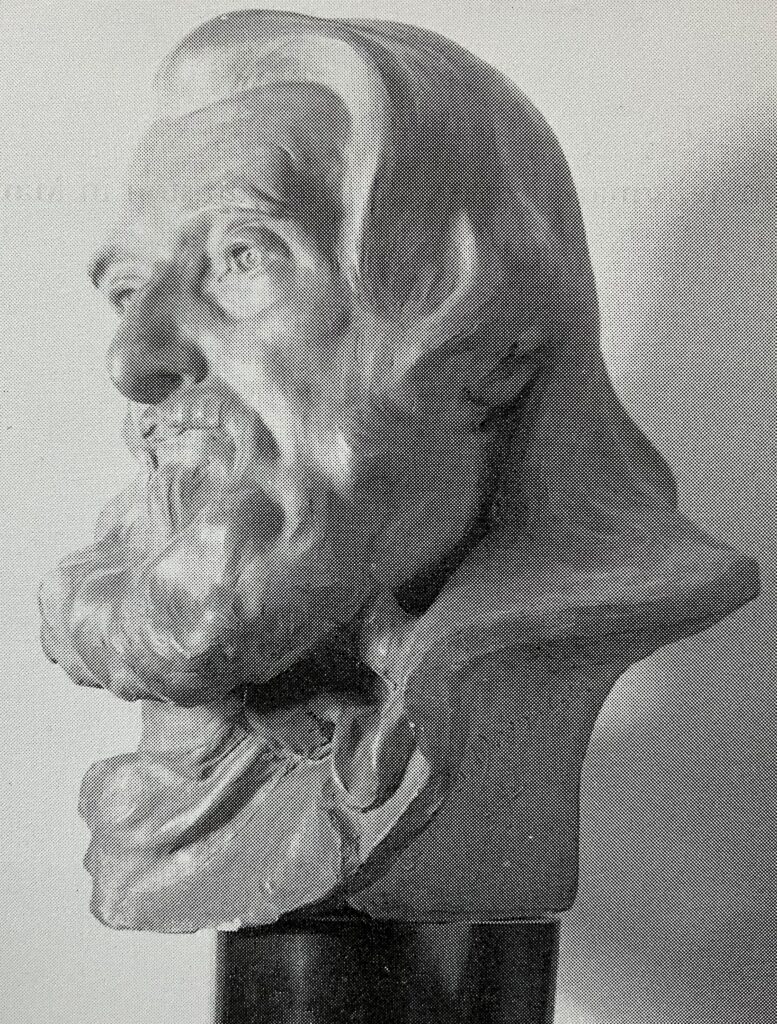

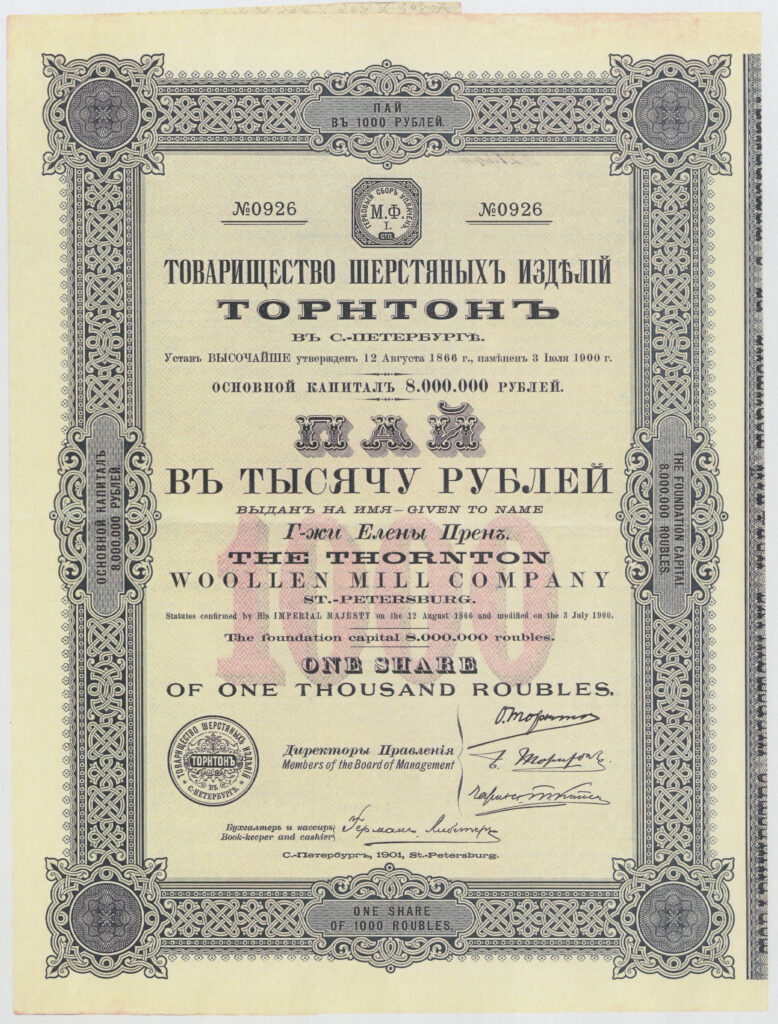

The Thornton Woollen Mill Company, founded by Thomas and Emma Thornton’s grandfather, stood from 1866 on the right bank (Oktyabrskaya Embankment) of the River Neva in St Petersburg, Russia. The factory quickly grew into a huge complex that provided work and basic living accommodation for thousands of mainly Russian employees who manufactured cloth using Yorkshire wool. In 1900, the company’s products won the highest awards at the World Exhibition in Paris. By 1901, it was an 8-million-ruble company.

The Thornton Woollen Mill works in St Petersburg, Russia

Thorntons was nationalized in the Soviet era when it was re-named the Red Weavers’ Mill, and employed 2,800 people by 1929 (see Yorkshire Evening Post, 18 April 1929). In 1992 it was re-privatized. The red-brick Nevskaya Manufaktura Building originally occupied by Thorntons was badly damaged in a ferocious blaze in 2021.

(For more on the company’s history, see Martin Varley, ‘The Thornton Woollen Mill’ in History Today: https://www.historytoday.com/archive/thornton-woollen-mill-st-petersburg published 12 December 1994.)

From 1900, Thornton’s manager was Willie Brooke, who was from Huddersfield, raising the possibility of another connection with George Thomson.

In November 1895 Thornton’s ran into trouble when about 500 weavers went on strike, under the direction of the St Petersburg League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class. The League strongly objected to cuts introduced by the factory management in the face of a slump in trade. The strike inspired no less a figure than Lenin to write (or possibly co-author) the pamphlet, To the Working Men and Women of the Thornton Factory. “Above all, comrades,” he exhorted:

“don’t fall into the trap so cunningly prepared for you by Messrs. Thornton.

“We must all keep a most watchful eye on the employers’ manoeuvres aimed at reducing rates [of pay], and with all our strength resist every tendency in this direction for it spells ruin for us …

“Turn a deaf ear to all their pleadings about business being bad: for them it only means less profit on their capital, for us it means starvation and suffering for our families who are deprived of their last crust of stale bread. Can there be any comparison between the two things?” —V. I. Lenin, ‘K rabochim i rabotnitsam fabrika Torntona’ [‘To the Working Men and Women of the Thornton Factory’] (1895) originally intended for Rabochee delo (Workers’ Cause) but published in Rabotnik (The Worker) (1896) no. 1–2 (1896), and collected in idem, Polnoe Sobranie Sochinenii [Collected Works] (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1972) vol. 2, pp. 84, 86.

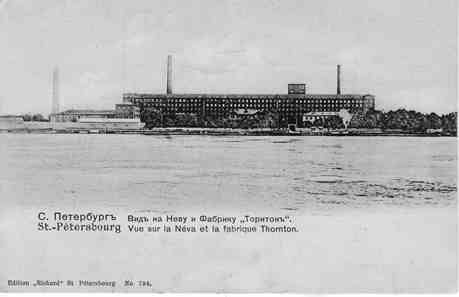

Lenin in 1895 (a police mug-shot)

This was one of Lenin’s first public calls to industrial and political action at what turned out to be the start of a career that would help bring about the Russian Revolution that overthrew the imperial rule of the Romanovs and replaced it with the new Soviet state led by Lenin himself.

This early example of Leninist invective was rooted investigative research.

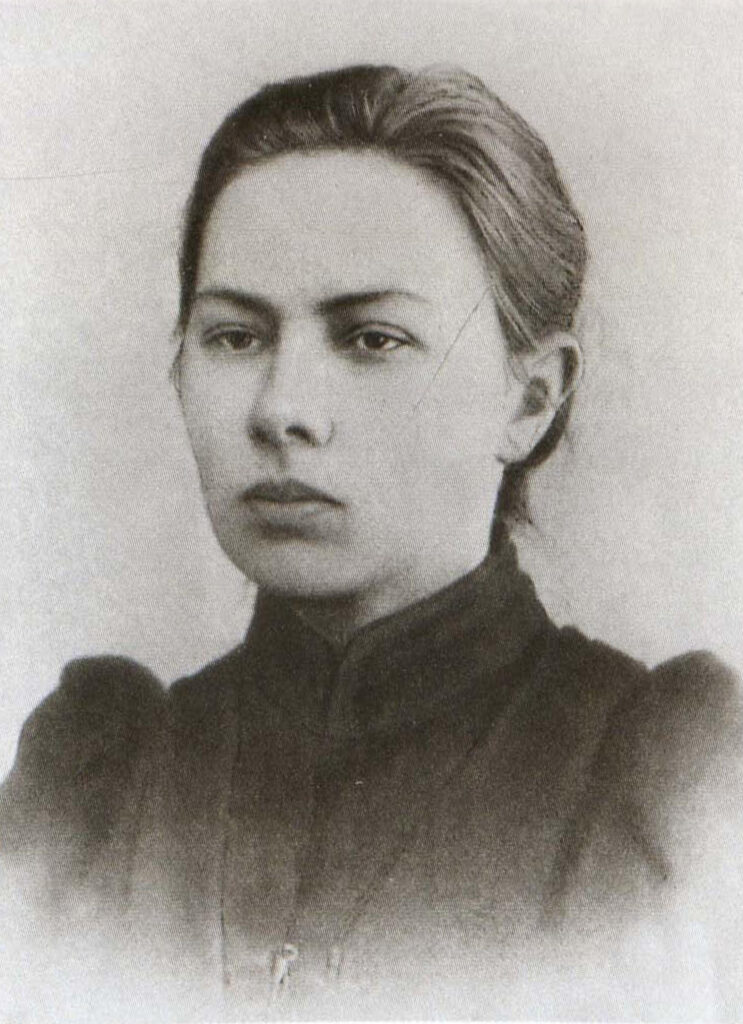

A young man called Krolikov, who worked as a sorter at the mill, alerted Lenin to working conditions at the company, and supplemented a bookful of notes with verbal evidence. Two young women, Apollinariya Yakubova and Nadezhda Krupskaya, both young friends of Lenin at the time, jointly responded to his request to investigate conditions at the Thornton factory complex.

The women donned shawls to disguise themselves as factory workers. They succeeded in gaining entry to a Thornton workers’ hostel in the Nevskaya zastava. They were appalled at the shocking living conditions they observed in both the men’s and the family quarters.

Krupskaya, who married Lenin in 1898, later recalled in her published reminiscences of her husband, how Lenin “collected and checked all the material very carefully” before penning his detailed and excoriating attack. “What a thorough knowledge of the subject it shows”, Krupskaya remarked:

“And what a schooling this was for all the comrades who worked at that time. That was when we really learnt ‘to give attention to detail’. And how deeply those details have engraved themselves in our minds.”

Nadezcha Krupskaya in the 1890s

The industrial action at Thorntons stimulated a series of strikes into the summer of 1896 involving 30,000 textile workers.

One of the most important books in Marxism-Leninism, The History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Short Course), first published in 1938 by International Publishers, recorded of Thorntons:

“These mills belonged to English owners who were making millions in profits out of them. The working day in these mills exceeded 14 hours, while the wages of a weaver were about 7 rubles per month. The workers won the strike. In a short space of time the League of Struggle printed dozens of such leaflets [as Lenin’s, addressed to the Thornton workers] and appeals to the workers of various factories. Every leaflet greatly helped to stiffen the spirit of the workers. They saw that the Socialists were helping and defending them.” (pp. 17-18)

By 1905, when the first wave of revolution swept Russia, Thorntons employed over 6000 hands (see London Daily News, 27 March 1905).

A Thorntons share certificate

Ruskinians will recall that in 1919 the Fabian socialist and playwright, George Bernard Shaw, filled with optimism about recent events in Russia, argued in a lecture given on the occasion of the centenary of Ruskin’s birth, that

“when we look for a party which could logically claim Ruskin to-day as one of its prophets, we find it in the Bolshevist party.” (Shaw, Ruskin’s Politics (1921), pp. 29-30)

Many in the audience laughed, and the subsequent history of the Soviet Union would arguably lend menace to Shaw’s assertion. Yet there is merit in Shaw’s apparent recognition that Ruskin cared more for social justice than for liberty, and on that basis, the point should not be entirely dismissed. An admirer of Ruskin who acknowledged his influence, Shaw later declared that

“Ruskin in particular leav[es] all the professed Socialists, even Karl Marx, miles behind in force of invective. Lenin’s criticisms of modern society seem like the platitudes of a rural Dean in comparison.” (See George Bernard Shaw, The Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Socialism and Capitalism (London: Constable & Co., 1928), p. 469.)

But the differences were not so much rhetorical as fundamental. Trotsky most effectively exposed them in an essay about Ruskin and machines that is almost completely unknown in Britain. Writing in 1901 under his real name, Lev Bronshtein, the then young Menshevik member of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party who was living in exile in Siberia, asked if “England remained deaf to Ruskin’s romantic appeals?” Believing it was, he asked “Should I regret this?” and replied emphatically, “I do not think so!”

Leaving aside what he characterised as “Ruskin’s reactionary romantic delusions”, Trotsky nevertheless strongly objected to what he thought was Ruskin’s failure to distinguish between the technical and social value of the machine. This is how he saw Ruskin’s argument and responded to it.

“[Ruskin argued that w]hen we learn that the tree’s leaves are adapted to the absorption of carbon dioxide and release oxygen, we become indifferent to them as to any gasometer.”

Ruskin’s view could be dismissed as mere “mysticism”, Trotsky insisted, and could be of no value. By contrast, there was Trotsky’s “realist” (Party) view that machines “achieve results” and admirably represent “the tireless struggle of human genius to achieve freedom from nature”. Moreover, he saw no poetry in what he described as peasants dragging heavy trees by hand when a steam locomotive could effortlessly transport ten thousand pounds of cargo.

As inadequately as Trotsky grasped Ruskin’s central argument here, he starkly underlines why those inclined to Marxism almost universally rejected Ruskin who was, after all, accurately described by Tolstoy as a “Christian moralist”, and not a materialist in the Marxist sense.

[For Trotsky’s essay, see Lev Bronshtein, ‘Poéziya, Mashina i Poéziya Mashiny’ [‘Poetry, the Machine, and the Poetry of Machines’] in Vostochnoe obozrenie [Eastern Review] no. 197 (8 September 1901).]

Nevertheless, it is worth noting that Ronald W. Clark recorded in his biography of Lenin that before the future Soviet leader parted the city of Berne on a visit in 1916,

“he coped into his notebook the titles of a number of books he was apparently preparing to borrow. They included ten volumes on aesthetics, five volumes of Ruskin’s Modern Painters, a book on Impressionism, and collections of Goethe, Victor Hugo, Dante, Byron, Schiller, Ibsen, Lessing, Daudet and Shakespeare. The list suggests that for once he had found gaps in his dedication to revolution and was preparing to stuff into them some non-utilitarian study of the arts.” (Ronald W. Clark, Lenin: The Man Behind The Mask (London: Faber, 1987), pp. 170-171)

There is one final twist in this unfamiliar and revolutionary Russian-Ruskin tale. Late in 1923, as Lenin approached death, his wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya — who had investigated the Thornton works back in 1895 — compiled A Guide to the Removal of Anti-Artistic and Counter-Revolutionary Literature from Libraries Serving the Mass Reader. The great writer and socialist Maxim Gorky wrote, with heavy irony, to a friend:

“Of news which stuns the mind I can inform you that Nakamine has printed this: ‘Gioconda, a painting of Michelangelo’ [i.e. in error for the Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci], and in Russia Nadezhda Krupskaya and a certain M. Speranskii have forbidden for reading: Plato, Kant, Schopenhauer, Vl(adimir) Solov’yov, Taine, Ruskin, Nietzsche, L(ev) Tolstoy, Leskov, Yasinskii (!) and many other similar heretics.”

He continued in all seriousness:

“I still cannot make myself believe in this intellectual vampirism, and I will not believe it till I see the Guide […] The first impression I experienced was so strong that I started writing to Moscow to announce my repudiation of Russian citizenship. What else can I do if this <atrocity> turns out to be true?”

(Letter dated 8 November 1923, and published in Hugh McLean (ed.), ‘The Letters of Maksim Gor’kij to V. P. Xodasevic’ in Harvard Slavic Studies, vol. 1 (1953) pp. 279—334, specifically pp. 306-307.)

The fact that the underprivileged communities of Sheffield, Letchworth and elsewhere in Britain should have benefitted from the progressive campaigning and philanthropic generosity of a Ruskinian whose family fortune was built on the hard toil of Russian workers is troubling to say the least.

To Thomas Thornton’s credit, he did bequeath two-fifths of his shares in Thorntons Woollen Mill to the Russian Technical Society which, under the chairmanship of the statesman and entrepreneur, V. I. Kovalevsky (1848-1935), recognized the legitimacy of Russia’s financial interest in a mostly foreign-owned company rooted in its land and labour. Perhaps as a counter-balance, however, he also left one-tenth of his shares to the Anglican Church in St Petersburg (see Globe, 17 June 1908).

Moreover, at an early stage in his political journey, Lenin convicted Thorntons of exploiting its St Petersburg workforce. His intervention in 1895, and the industrial unrest among Russian textile workers that followed it, was an important early step on the long road to the revolution that, in 1917, changed Russia and the world.

Please send any feedback to contact@stuarteagles.co.uk