In this third and final blog about Ruskin curator, William White, we consider his troubled relationship with Sheffield—its people, places, and most of all, the city council. Never content with the practical reality of living at Meersbrook Hall, he found himself at odds with the municipal authorities which, unhappily, also employed him. His sincere dedication to his museum work was eventually undermined by a sense of self-importance that tended to make him tactless, and ultimately led to his brutal dismissal. He considered his detractors ignorant, even dishonest, and with some justification regarded his treatment as unjust. He spent the rest of his life in relative obscurity, still committed to the more scholarly work at which he excelled.

-

WILLIAM WHITE,

CURATOR OF THE RUSKIN MUSEUM:

(III) THE END OF THE ROAD

Stuart Eagles

WHITE’S TROUBLED RELATIONSHIP WITH SHEFFIELD

The roots of William White’s sacking, and his ultimate failure as the Ruskin Museum’s curator, are to be found in his negative views of Meersbrook Hall, Sheffield’s municipal authorities, and local, casual visitors to the Guild’s collection. He was never truly at home in the town, and he made his ever-increasing feeling of discomfort painfully obvious. Perhaps his upbringing in the comfortable surroundings of Morden Hall, and the sizable financial cushion that he had inherited, combined to encourage a feeling of entitlement, which was fuelled by nostalgia, and sustained by the privilege of not needing to care much about earning an income. His life before Meersbrook had also been spent in London, or on its rural fringe. Life in an industrial town in the north of England must have come as something of a culture shock.

Nevertheless, in 1893, White painted this charming and keenly observed picture of life at Meersbrook Hall in a letter published in the scientific journal, Nature:

“FROM the window opposite, as I write, I have just witnessed an interesting performance on the part of two horses. Bordering the park is a strip of land, doomed to be built upon, but meanwhile lying waste, and used for common pasturage, on which the horses under notice were leisurely grazing. A pony in a cart, having been unwisely left by the owner for a time unattended on the grass, suddenly started off, galloping over the uneven ground at the risk of overturning the cart. The two horses, upon seeing this, immediately joined in pursuit with evident zest. My first supposition, that they were merely joining in the escapade in a frolicsome spirit, was at once disproved by the methodical and business-like manner of their procedure. They soon reached the runaway, by this time on the road, one on one side of the cart, and one the other; then, by regulating their pace, they cleverly contrived to intercept his progress by gradually coming together in advance of him, thus stopping him immediately in the triangular corner they formed. Until the man came up to the pony’s head they remained standing thus together quite still; when the two horses, evidently satisfied that all was now right, without any fuss trotted back again together to their grass.” (Nature, vol. 48 (29 June 1893), p. 199: my emphasis)

Those ominous words, “doomed to be built upon”, neatly express White’s mounting dissatisfaction and discontent with the way things were developing away from the idyll he evidently relished sharing.

Indeed, a report in the Manchester Guardian on 6 March 1895 was unflattering in its description of the Ruskin Museum’s situation and surroundings.

“Truly the Sheffielder has need for the suggestion of ideas of beauty, for the daily surroundings of his life are bleak and soot-begrimed beyond the average even of manufacturing towns. Even the museum, though it stands in an old domain, on a pleasant green slope, is faced by an eyesore, in the shape of a row of hideous cottages whose gaunt backs are turned blankly towards the lower edge of the park. It is a bold defiance of actual conditions which has placed the Ruskin Museum on the hillside overlooking the smoke and grime of Sheffield.”

Commenting in 1902, William Sinclair of the Glasgow Ruskin Society conjured up an equally bleak and damning picture.

“Within recent years […] the Corporation—in its wisdom, or lack of it—has drawn off the stream [running through Meersbrook Park] and allowed buildings to be erected all round the borders of the Park, for the housing of its Citizens, for to-day Sheffield, like other large cities, is extending in all directions, and what a few years ago were country lanes bordered with wild flowers, is now part and parcel of the city. Brick Villadom with the usual stucco fronts and porches now line the fringes of Meersbrook Park; the jerry-builder has had his chance for good investments, with the result that, in a great measure, the natural beauty of the Park has been considerably diminished, not to say destroyed, and the homes of the people are of such a character that—well, to put it quaintly—the souls of Gothic architects would have an uneasy time of it, if they were to revisit the glimpses of the moon in the vicinity of Meersbrook Park.” (William Sinclair, “The Ruskin Museum at Sheffield: What It Is, and What It Might Be”, in Saint George, vol 5, no 20 (October 1902) pp. 263-282,, specifically p. 271)

Not only was more and more parkland being given over to housing, but there always seemed to be a problem with the mansion itself, which doubled as White’s residence and workplace. In the summer of 1891, the Borough Surveyor, Charles Froggatt Wike (1848-1929), discovered that the grey slate covering the roof had perished to the point that it leaked. In the course of the following summer, the museum was closed while the roof above the Library and Mineral Room was replaced with a raised glass structure by Thomas Fish & Son of Nottingham. In the previous winter, four new lamps had to be purchased to improve lighting in the Picture Gallery, and the uneven floor of the Mineral Room was re-laid, necessitating a new ceiling in the rooms on the groun floor below it, including the Committee Room.

A constant stream of alterations and improvements were made. On the one hand, this demonstrates the willingness of the management committee and city council to spend money where it was needed but, on the other, it underlines just how much work needed to be done. For instance, in 1893-94, a kitchen range was installed, the floor of the Turner Room at ground level was covered in lino, and the mottoes on the friezes of the walls of the museum were re-painted. In August 1895, the borough surveyor recommended unspecified work on the museum’s exterior. In February 1897 a separate high pressure water meter was commissioned from the Water Department in the name of fire safety, and a new kitchen sink and tap were installed, while in May repairs were made to the ever-troubling water closets and drains, and in October repairs were made to the fairly new skylights.

White seems to have become a writer of frequent letters of complaint to the authorities. One example, addressed to the General Purposes and Parks Committee of Sheffield Council, and published in the Sheffield Independent on 7 November 1896, is worth quoting in full because it gives a sense of the nature of White’s discomfort, and his manner of expressing it.

“The roads leading to the Meersbrook Park, which have from the first been so shockingly bad as to be frequently quite impassable, have lately become still more deplorable, till they are now quite a quagmire and dangerous to traffic. Often it is impracticable for foot passengers to cross the road anywhere, and I have often heard of their having to turn back. Thus the use of the museum has been affected to such am extent during the last few months as to cause a decrease—instead of a regular increase in the attendance, as in former years—of over 7,000 visitors. Cab drivers have so often refused to come along the roads, and my wife having sometimes been in fear of the cab being overturned even, I have lately exercised my privilege of using the drive at the bottom gate of the park, especially in the dark. I found, however, a few evenings ago that, on the authority of Mr Hemming, the gate had been made fast to prevent me from using it. As an official of the Corporation (and resident here, unfortunately), I have a perfect right to use the Park road, and I shall esteem it if you will please give orders that the gateway be made free to me at all times. Objection, I find, has also been taken to the head gardener (Mr Knowles) and one of his men having opened up a faulty sewer, as on two previous occasions, when required, for promptly clearing and flushing the same, at my request. The state of the drains here generally is still such as to render the very old building unfit as a dwelling house, and really equally unsafe as a museum, the basements being undermined by springs and stagnant water. Yesterday, the cellars were flooded again, the roofs and windows of the museum rooms let in water still, and the walls elsewhere remain damp. This I am having investigated, and as it more concerns my own [Ruskin Museum] committee, I will bring the matter before them in due course. I am constantly asked by visitors to agitate with regard to the state of the roads, and I have several times seen the Derbyshire authorities respecting them, with but little effect. But as half the roads which bound the park undoubtedly are the property of the Corporation [of Sheffield], I believe it really comes within the province of your committee to deal with them.” (My emphasis)

Less than a fortnight later, a regular columnist in the Sheffield Independent consciously or otherwise echoed White’s complaints:

“the Ruskin Museum, alas, is only good […] at a very considerable distance—so far away in fact that it cannot be seen—[…] to approach it is to be prejudiced against it. I happened to take a friend there only yesterday. He had never been in Sheffield before, but he wanted to see the museum till he got within a few hundred yards of it and then he wasn’t so enthusiastic. A ploughed field is a cleanly and comfortable thoroughfare compared with the ground we covered on our way to the repository of some of the richest art treasures in the country. Whether you take the road or make a short cut across the alleged field the result is the same—mud to the right of you, slush to the left of you, and a general incentive to get back on to dry land all around you. Surely something can be done to make this treasure house more approachable?” (19 November 1896)

If White was undiplomatic, even tactless, in his robust criticism, it did not mean he was essentially wrong. There is no doubting his sincerity and seriousness of purpose. He told Ruskin’s friend, and one of the most generous of the St George’s Guild’s Companions, Mrs Fanny Talbot, that when he had first written to her,

“I was under the impression that you were fully acquainted with Professor Ruskin’s intentions when starting the Museum at Walkley, but apparently you are not in possession of all the facts of the case.

“I would first say that I trust you do not imagine that I do not respect and am doing my utmost to jealously guard Mr Ruskin’s aim & high purposes, as greatly or even more—than any other of his admirers otherwise I would not be here. But I am in possession of & have made it my business to obtain all that is to be known of the details of Mr Ruskin’s project respecting the museum & that knowledge is what I am guided by when I said that I hoped to make the museum more, as a monument to him, I was thinking of the enrichment of illustrations to his works & such personal archives that he himself naturally did not include.

“I may however tell you, upon his own authority that the collection at Walkley was but a nucleus of what he proposed for the single museum. All the lines are distinctly laid down, & I am now—of course under the Trustees simply endeavouring to render everything intelligible & complete as possible. There are all the objects that were lying at Bewdley & elsewhere scattered, now here, & many others at Brantwood & other places not yet collected, to be considered which probably you have quite forgotten. These are being dealt with, as far as funds allow, & made available.

“Otherwise the line of demarcation is strongly defined & as you may see from my prefaces to the catalogues already published, I am ready enough to uphold the exclusive character of the collection. More I think I need not say.” (4 November 1892: White’s emphasis).

This sincere but overly defensive response to Mrs Talbot’s evidently less than obliging reply to his initial letter, shows how he tended to dig in rather than back down, and to underline what he was certain was his superior knowledge. His dedication was absolute, but his conviction that his own opinion must be the right and only one would prove to be increasingly problematic. His condescending tone, and his prickly over-sensitiveness, won him no friends.

In 1894, he publicly took issue with a comment published in a Birmingham newspaper, which stated that:

“One of the most interesting features of the Ruskin Museum at Sheffield is the series of drawings of ancient buildings and pictures placed there one by one by Mr Ruskin as they were completed under his direction. Since 1887, the additions have been few, Mr Ruskin’s ill-health having prevented him from superintending the work. An effort is now being made to carry on this work; but as the museum at Sheffield is already well stocked and it is moreover felt that it is desirable to let the contents remain as far as possible as Mr Ruskin himself placed them, it is intended to place the new drawings in the Municipal Art Gallery at Birmingham where they will be accessible to a large body of students and art lovers.” (Qtd in Sheffield Evening Telegraph, 27 February 1894: my emphasis).

After quoting this passage, the Sheffield Evening Telegraph turns to White’s comments, which seem totally to ignore the point that “[a]n effort is now being made to carry on this work”:

“Mr White challenges the accuracy of the statements concerning the Ruskin Museum, and calls attention to the existence of the St George’s Guild, whose trustees act for Mr Ruskin, and continue to effect the scheme of the museum as fully as its unaided funds admit of. Mr White continues:—‘During the last few years, since the Corporation of Sheffield has liberally undertaken the external maintenance of the museum, more has been possible than formerly, and several drawings of the mosaics of St Mark’s, Venice, have quite recently been added to the collection, in addition to very many other drawings and objects acquired by gift or purchase. Among the latter may be mentioned two drawings by Sig. Alessandri (referred to in your notice), one of the staff of exceptionally able artists whom Mr Ruskin trained so highly for the production of such work—namely, a full-size copy of the head of St Ursula in Carpaccio’s famous picture in Venice of “St. Ursula’s Dream”, one of the series of paintings about which Mr Ruskin has written so fully; and “The Stoning of St Stephen”, after Tintoretto. The latter, a masterly re-production in transparent water-colour, of such quality as can nowhere else be seen, has only just been procured; and the purchase of other works by this marvellous copyist are still in contemplation, including a further commission that will occupy him for many months to come. In fact, since the alteration in the management in the year 1889, when I was appointed to the charge of the museum, several hundred drawings which had never been seen by the public previously have been delivered, and carefully framed for exhibition here. Some of these were forwarded from Brantwood, London, and elsewhere, the majority having been kept in store or on loan until they could be duly dealt with at the museum; while many other works are still awaiting similar treatment. Several objects have also been lent during this term to the Birmingham School of Art, and also for exhibition at Huddersfield and Liverpool. At the present time, it may be of interest to know, a somewhat voluminous handbook to the art portion of the collection, upon which I have been occupied for a considerable period, and which will form an introduction to the art-teaching of Mr Ruskin, as illustrated by the examples in the museum gallery, is in the press, and will shortly be issued by Mr Ruskin’s publisher. Thus it will be seen that the operations of the museum continue to progress in the manner Mr Ruskin heartily desired, and that his programme of future work is being adhered to persistently, with the greatest regard to the scope which he has very specifically defined, nothing being admitted of any kind but what he would undoubtedly most thoroughly approve.’” (27 February 1894)

White always responded robustly to criticism of the museum and of himself, often adopting an overbearing tone. He was thin-skinned and testy. On 25 April 1890, shortly after the museum opened, White responded to what he dismissively labelled “a rather paltry letter” in the press, “affecting to present a true idea of the average character of those who are attracted by the treasures stored in the Ruskin Museum” (Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 30 April 1890). His tone was not calculated to win over doubters or detractors, and his alternative account, which he grandly proclaimed was the “authentic representation of both the quantity and quality of the ‘Society’ visiting the Ruskin Museum at Meersbrook Hall” must have struck many local residents as pompous in the extreme. White followed up with an exaggerated, yet absurdly ungrateful claim: the visitors were “multifarious”—”numerous beyond all expectation, so that at times the rooms are inconveniently crowded”. Although he’s proudly highlighting the museum’s popularity, he also seems to be saying that it might be even better if only all those pesky visitors didn’t keep getting in the way.

Readers of the Sheffield Independent were told by the same regular columnist quoted earlier that when he and his friend got to the museum via the virtually impassable roads,

“it was closed, the rule being that the institution closes at dusk, consequently we were not admitted. As law abiding citizens we did not grumble at that, but it certainly struck me that if the museum were opened for an hour or two in the evening it might be an advantage. It was tried, I understand, some years ago, but people did not care to walk up there in the evening. At that time of day, however, the building stood by itself, with no near neighbour at all. Now this district is so built in that a large and thriving community has been formed just outside the gates of the park. These people are engaged during the day, and can only spare an hour for artistic study in the evening. Besides, I believe it to be the fact that Ruskin’s express desire was that the museum should be in an industrial part of the town, so that it might have an edifying influence on the working classes. In that case it is evident that an evening opening is essential to the attainment of the object in view.” (19 November 1896)

The only obvious concession made to workers when it came to opening times, however, came on 28 June 1893 when the council resolved henceforth to open all its museums—Weston Park, the Ruskin and the Mappin—on Good Fridays.

A DOG’S LIFE

White was not shy to complain, but he also provoked complaints. The worst instance occurred early in 1895. White was sued for damages at Sheffield County Court by Mrs Annie Bramhall, who had been bitten by his large and apparently dangerous dog—a mastiff/St Bernard cross. White was defended by William Edwin Clegg (1852-1932), the football player turned solicitor and local politician who had attended the opening of the Ruskin Museum with his father, W. J. Clegg (who frequently attended early meetings of the Ruskin Museum Committee in his capacity as Mayor of Sheffield).

The attack took place on 9 December 1894, at the Heeley Decorative Company’s London Street store, where Mrs Bramhall’s husband worked as a decorator. George Parkes, the Ruskin Museum’s 46-year-old caretaker, visited the shop while out walking White’s dog. Mrs Bramhall was hanging up a towel when the dog flew at her and bit her on the breast. This necessitated medical treatment which lasted on and off for a month. H. D. Evans, the owner of the shop, who was present and witnessed the incident, told Parkes that had he been in charge of the dog he would have “either knock[ed] lumps off it or kick[ed] its life half out”—a notion apparently so absurd or horrifying as to provoke laughter in the public gallery of the court. The trial descended into farce when Evans recalled Parkes telling him

“how on one occasion he had a regular stand up fight with the dog, which lasted over an hour. The dog eventually got under a bench, and Parkes fetched him out and finally throttled him over a vice on a joiner’s bench. (Laughter.) Parkes added that when the fight finished both he and the dog were covered with blood from bites, but there was no danger to him, as he had been bitten so many times before.” (Sheffield Evening Telegraph, 28 February 1895)

Parkes, who was called as a witness for the prosecution, went on to describe White’s dog as a “big brute” (a comment that again occasioned laughter). What White made of this testimony may only be guessed at, though there is no evidence that he attended court himself, nor that he harboured any grudges against Parkes. For the defence, Clegg called John William Wragg, the manager of the Highfield branch of the Sheffield and Hallamshire Bank, who said that the dog had often played with his children without showing the slightest signs of violence. The case was adjourned, but White was subsequently found guilty of causing harm, as the owner of a dangerous dog, and was ordered to pay Mrs Bramhall’s legal and medical costs of £12 17s. 6d., plus £25 in compensation for her injury and inconvenience. Although Mrs Bramhall won the case, there is little evidence that the male lawyers and judge had any sympathetic understanding of her painful experience, or any desire to gain one, instead preferring to discuss the legal niceties of a dog-muzzling order then in force in the city. It was a conversation that became so convoluted and muddled that the public gallery again erupted into hysterics.

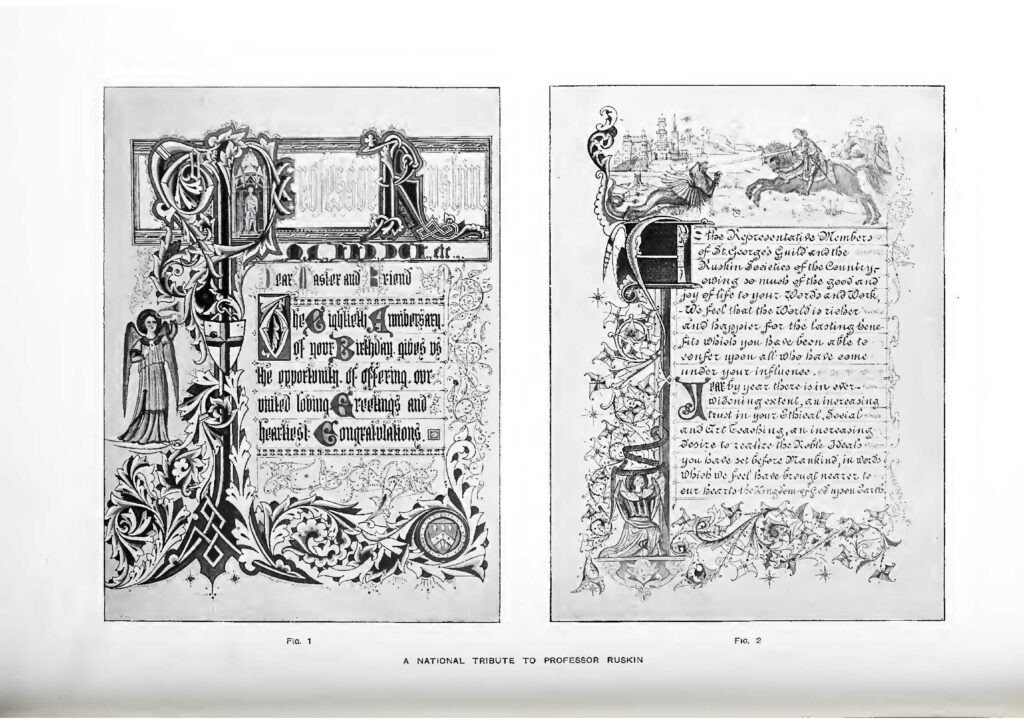

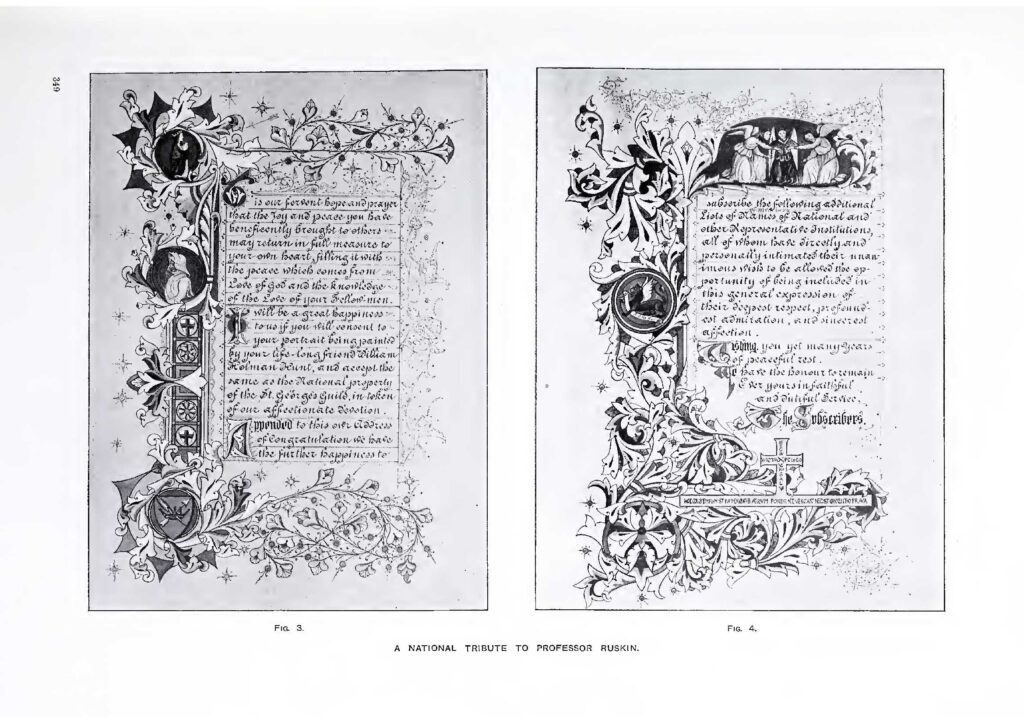

THE ILLUMINATED ADDRESS FOR RUSKIN’S 80TH BIRTHDAY

The illuminated address prepared to congratulate Ruskin on his 80th birthday, and to celebrate his lifetime’s achievement was, on the one hand, a triumph for William White and testimony of his diligence, and, on the other, a diplomatic blunder that was a key part of his downfall as curator of the Ruskin Museum. Of this last point, it will suffice to mention here that whilst White named himself as the secretary of the committee responsible for producing the address, the completed address failed to name his bosses on the Ruskin Museum Committee. It is impossible to know if this was a genuine oversight or a calculated slight, but the omission certainly caused offence.

In 1879 the newly formed Ruskin societies inaugurated what became a tradition of sending Ruskin a congratulatory address on his birthday. Twenty years later, for Ruskin’s milestone 80th birthday—and, as it turned out, his last birthday, too—he was presented with a breathtakingly beautiful and meticulously produced illuminated address on 24 leaves of bound uterine vellum. As White would later put it:

“Never did the general feeling of reverent admiration and affectionate esteem with which the late John Ruskin was regarded find fuller and happier expression than on th[is] occasion [… It] was of such significance and comprehensive importance as to render it a document of an almost national character.” (William White, “A National Tribute to Professor Ruskin”, in The Magazine of Art (March 1901), pp. 260-265, specifically p. 260: it is worth noting that in April 1901 White gave a copy of the journal, containing this article, to the Ruskin Museum.)

The idea of presenting Ruskin with an illuminated address had come from William Sinclair, the Secretary of the Ruskin Society of Glasgow, whom White must have met when he addressed the group in March 1896, and when Sinclair visited the museum. Under the scheme adopted, not only would subscribing members of the local branches of the Ruskin Society be named, but so would Companions of the Guild of St George. As White explained, the address would also name “the many royal associated bodies and other representative institutions which had been connected in a direct or indirect manner with the Professor’s life-work and influence” (p. 260). The organisations were presumably approached by the committee, and their consent received. They included the National Gallery and the British Museum, the Royal Academy of Arts, the Royal Society of Painters in Water-Colours, the Ancoats Art Museum (Manchester), the Art for Schools Association, the Royal Institute of British Architects, the Dűrer Society, the Royal Society of Literature, the Fitzwilliam Museum (Cambridge), the Geological Society of London, the Mineralogical Society of London, the Kirkcudbright Museum Association, the National Trust, the National Society for Checking the Abuses of Public Advertising, the Selborne Society. the Ruskin Linen Industry (Keswick), the Keswick School of Industrial Arts, and Whitelands Training College.

The “Magazine of Art” in which White’s article about the illuminated birthday

address appeared.

The process of producing the address was overseen by the committee, apparently chaired by White, who also served it as secretary, and meetings about the project were held at the Ruskin Museum at Meersbrook. White was responsible for “the selection of the emblematic subjects introduced as vignettes and miniatures, or otherwise, included in the decoration of the pages, and the general planning out of the work” (p. 261). The text of the address was composed by the secretaries of the Ruskin societies.

The completed address was bound by T. J. Cobden-Sanderson (1840-1922), who undertook the work pro bono and in gratitude for Ruskin’s influence upon him. When Cobden-Sanderson presented Ruskin with a copy of Unto this Last which he had exquisitely bound—one of the gems in the library of the Ruskin Collection—he wrote, “It has long been my desire in some speechless way to express my boundless admiration of you and your work. Deny me not the gratification of this desire. I have laboured with love, and in my gift I would speak it out” (qtd in Sinclair, p. 278). Describing Cobden-Sanderson’s work on the illuminated address, White wrote that

“[t]he binding consists of a loose cover of plain unbleached parchment, the folded leaves of vellum being held in place by a narrow ribbon of silk of a pale green colour; the simple decoration on the side being limited to the inscription, ‘To John Ruskin, on his Eightieth Birthday’, within a laurel wreath, with the four figures of the year of his birth outside, in gold lettering. The album is further protected by a handsome box covered with red morocco, also furnished by Mr Cobden-Sanderson” (p. 263).

(Abve and below) Some of White’s monochrome photographs of the Illuminated Address

The illuminating artist was Sheffield’s Albert Pilley (1840-1902), who (according to White) claimed “that no previous work of the kind ha[d] ever been produced of so elaborate a nature in the conception of the embellishment of its borders, which were extended to every page of the appended lists of engrossed names of ‘the subscribers’” (p. 261). The “designing of the floriated borders and scrolls, and of the capitals in which the chosen subjects were to be introduced” was Pilley’s work, and “looking upon the production, in fact, as his masterpiece, [he] spared no pains or toil to render it acceptable and pleasing to the eye of the master-critic” (p. 260).

It is hardly surprising that Pilley’s painstaking work, in which he appears to have been assisted by his daughter, Genevieve (who was also White’s assistant at the Ruskin Museum), took months to complete. The scale of the task had initially been sorely underestimated by the committee, such that Ruskin was first presented with only a few pages of it in February 1899. The completed address was fully photographed in Sheffield by White before being sent to Glasgow where it was exhibited for the interest of members of the Ruskin Society there. Finally, on 10 August 1899, the initiator of the project, William Sinclair, delivered the finished work to Ruskin at Brantwood.

Given what a triumph the illuminated address undoubtedly was, it must have been a considerable personal blow to White to find that the failure to include the names of any of the members of the Ruskin Museum Committee gave rise to resentment and recrimination. He maintained that it was an oversight, and entirely accidental; some Sheffield councillors, apparently humiliated, seem to have suspected that it was a deliberate slight on White’s part. Consequently, in retrospect, some members of the Ruskin Museum Committee resented the time he had spent working on it. His days at Meersbrook were numbered.

WHITE’S SACKING

On 4 May 1899, at a meeting of the Ruskin Museum Committee attended by Sheffield Councillors Joseph Gamble, W. H. Brittain, G. J. Smith, Roberts and Colver, it was resolved to recommend that three months’ notice be given to White to terminate his engagement as curator.

The precise circumstances that had brought this about were explored at a general council meeting on 10 May, at which the relative merits of the Ruskin Museum Committee’s recommendation were debated. The discussion reveals the fault-lines along which the relationship between Sheffield Council and the museum’s Guild-selected curator finally broke.

There was by no means universal agreement in the council about what to do—even among members of the Ruskin Museum Committee itself. Alderman Gamble, then chairman of the RMC, was the most uncomfortable with the resolution to serve notice on White. Alderman Brittain who, like Gamble, was a veteran member of the committee, commented that he “shrank very much from bringing personal questions before the Council in this public way” but he nevertheless maintained that the committee had been left with no alternative (Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 11 May 1899). The RMC had reached the decision that it was by then “absolutely impossible for them to work amicably with the curator”. In February, following the dispute over the illuminated address, they had given White the opportunity to resign quietly, but he had refused to do so.

Joseph Gamble

Councillor Richard Langley, a member of the RMC since November 1895, complained that White “had not, in many instances, obeyed the orders of the committee”. Moreover, Langley claimed, White had passed “very severe strictures” on the chairman, a point that the generous and even-handed Gamble sought to play down. Worst of all, Langley concluded, White “was not courteous to the people who visited the museum”, a statement that provoked supportive shouts of “Hear, hear”. Nevertheless, Gamble maintained that these charges of incivility were, in his opinion, exaggerated.

It is clear that these matters were brought to a head by a row that developed between White and certain members of the RMC. It followed an apparently unannounced visit to the museum by Cllrs Langley and George Jackson Smith (who had joined the committee at the same time as Langley). During their visit, the councillors inspected the kitchen at Meersbrook Hall and found that certain instructions they had previously given White, details of which were not disclosed, had not been carried out. There had been vague hints in RMC minutes of discontent connected with the curator as far back as October 1896.

Unhappy with their inspection, Cllrs Langley and Smith summoned White to meet them there and then in order to explain himself. The fact that a major meeting of the RMC took place a little over a week later, with the Lord Mayor, Ald. W. J. Clegg, as well as both Baker and Thomson from the Guild in attendance, and almost all other committee members too, indicates the scale of the crisis that had ensued, even though the minutes themselves are deliberately vague and give very little away.

The council meeting held on 10 May to debate the RMC’s resolution to sack White descended into comic melodrama, with White cast as a cross between William Dorrit and Pecksniff. White had answered the call of Cllrs Langley and Smith, and had reportedly said to them, “Am I wanted? I am a gentleman; I know where to meet gentlemen; I meet them in the dining room, not in the kitchen. I am a gentleman. It is an insult to me”.

Some councillors expressed their discomfort and scepticism when Langley asserted that “the kitchen was not a private apartment. It contained a joiner’s bench as well as kitchen conveniences, and they did not intrude on Mr White’s premises in the slightest degree” and, on that basis, he maintained that no notice of the councillors’ visit had been necessary. White had disagreed and argued that the kitchen was part of his private residence, not the public museum. Furthermore, he had objected to being reprimanded in the kitchen “in the presence of his own servants”.

Langley seems to have inferred rather more than is obviously justified by this encounter, going on to say that if the episode represented “the attitude of Mr White to members of the committee […] what would be his conduct to the ordinary visitor”? The insinuation was clear.

Smith confirmed Langley’s version of events, and agreed that it was not in the public’s interest for “White to remain in post, though he added that White had admitted that the incident took place and ‘had offered ample apology’ for it”. White’s “most humble apology” was referred to several times by the sympathetic Gamble who, though careful not to excuse White’s conduct, asked that the Council give the man another chance, something in which, he said, the trustees of the Guild, Baker and Thomson, supported him—a fact that White would also later highlight. The discussion seems to have gathered its own momentum. It was even suggested at one point, for example, that the museum’s average of 120 visitors per day was so disappointing as to imply that the curator was doing something wrong and that the museum was not “answering the purpose for which it was intended”, but no evidence was offered in support of this claim and no alternative explanations were considered.

Indeed, Cllr Hughes, with apparent justification, contended that, “All that had been said had been innuendo”. Ald. Muir Wilson and Sir C. T. Skelton cast doubt on claims of White’s discourtesy to visitors. The meeting very nearly collapsed when a complaint by White to the Parks Committee was read aloud so badly that one councillor sarcastically called for a translation, while the clumsy reader himself condemned the letter not once but twice as “dictatorial”, whilst yet another councillor declared that he could see nothing wrong with it. Another still, expressing admiration for the letter (perhaps with some hint of irony), quipped that “as the evidence grew in volume he felt less inclined to vote for the resolution” to dismiss White (my emphasis).

Councillor Chambers got to the heart of the matter when he said that “it was perfectly evident even from the apologetic tone adopted by Mr White’s supporters that there was a very great deal that had not been told. It was the plain duty of the Council to support the [Ruskin Museum C]ommittee”. This was the point. In the end, the decision to sack White rested on the Sheffield councillors’ belief that “if Mr White won this case the committee must retire. That would not be dignified or proper.’ It was a power struggle the council could not afford to lose.

Councillors felt that it was incumbent upon them to convict White of incivility and to sack him. The Lord Mayor—Ald. W. E. Clegg, who had earlier unsuccessfully defended White in the case of his dangerous dog—passionately approved of White’s sacking, claiming that “[White’s] manner was not agreeable to people who visited the museum, and there were no fewer than four instances when it was alleged he had insulted members of the committee”.

The council’s authority was at stake, and by “an overwhelming majority” its members voted for the minutes of the Ruskin Museum Committee to be adopted and for the resolution to dismiss White to be approved. Many councillors had concluded that the high-handed White was a troublemaker and a liability. They had had enough of his attitude of superiority and his blunt complaints about his general feelings of dissatisfaction.

Inevitably, the long report of this council meeting published in the press provoked letters from the public. Edith A. Marples of Endcliffe Avenue wrote:

“I know nothing about the rights and wrongs of the case, but, as I see it mentioned in one of the speeches ‘that Mr White had not treated with courtesy, people who had visited the Museum’, I may mention, that on taking my sister (a stranger to Sheffield) to see the Museum, a short time ago, we were treated with exceptional courtesy, and the curator went out of his way in order to show us the treasures under his charge in the library.

“Perhaps, any citizens who have been treated in a similar manner, will write to the papers and say so.” (Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 12 May 1899)

Some readers did just that. “A Frequent Visitor”, answering Mrs Marples’s appeal, testified to White’s “natural, and therefore, untiring courtesy to any visitor who is, even in the smallest degree, interested in the specimens or the aims and objects of the museum” (Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 13 May 1899).

A few days later, a report noted that the Chesterfield Students’ Association had been received by Mr White at the museum and—one might add, in spite of everything—they were conducted around the collection: “Mr White was cordially thanked for his courtesy and the readiness with which he supplied any information asked for” (Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 15 May 1899). Mary G. Addy, of Westbourne Road, remarked that, “Two members [of the RMC] seemed to have a personal dislike to Mr White, and do not scruple to indulge it”. At the end of a long letter in White’s defence, she concluded with her damning verdict that “[a]n onlooker would go further and say that there was no case presented against Mr White. The evidence was against the committee” (Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 17 May 1890).

In the same issue, an even more robust defence was mounted by William Sinclair of the Ruskin Society of Glasgow (the initiator of the illuminated birthday address). He wrote that “[n]othing ha[d] caused” him more “pain or surprise” than White’s sacking:

“Mr White is a gentleman and a scholar of repute. He has during the past nine years discharged his duties as a public servant in an exemplary manner, and has added to the popularity of the Ruskin Museum by his many gifts, as well as by his pen […]. I have known several gentlemen go from Glasgow to Sheffield, and they all speak in the same manner of Mr White.” Interestingly, although the Liberal Sheffield Independent acknowledged receipt of this letter, it refused to print it, declaring, “We consider […] that this is hardly a proper subject for newspaper discussion” (17 May 1899). It was certainly one way to save Sheffield Council further embarrassment.

White, who was smarting, wrote privately on 19 May to William Wardle, the Secretary of the Guild of St George. His sincerity and dedication are obvious, but so are his hubristic snobbery, pomposity, and lack of tact.

“My detractors take no interest whatever in Mr Ruskin, nor in the Museum—only in trying to prop up and patch up the worn-out old structure [i.e. Meersbrook Hall] which it is impossible to keep weather-proof—and never have. Lacking refinement of thought, and having no capacity for appreciating anything Mr Ruskin had to write about, they have made it as difficult for me to carry out Mr Ruskin’s purposes—the sole reason for my coming here—as possible […]

“If anyone will take up the work with more devotion than I do, knowing as much as I do of the minute details of Mr Ruskin’s intentions and designs in this connection, by all means let me make way for him. But being innocent, I cannot quietly submit to such injustice, though if it were not for my Love of Mr Ruskin, and my anxiety lest his wishes and plans be desecrated and overthrown, it would be the greatest happiness to me to be free from the bitterness of disappointed hopes, and from the surroundings which make me miserable in this wilderness of basic slag and refuse.” (Qtd in James S. Dearden, ‘Ruskin’s Illuminated Addresses’ in idem, Further Facets of Ruskin: Some Bibliographical Studies (Bembridge: James S. Dearden, 2009), pp. 187- 202, specifically pp. 200-201)

White did not respond publicly to the controversy until 12 June, by which time we must suppose that he had abandoned the “good hopes that something may yet be done to prevent a public disgrace and scandal”. He wrote an open letter to Henry Sayer, Sheffield’s Town Clerk, which was published in the Sheffield Daily Telegraph three days later. White started by objecting to his dismissal on technical grounds, citing the absence of the two Guild trustees from the crucial RMC meeting at which the resolution recommending his dismissal was passed. More seriously, he contended that “no evidence of any kind, and no witnesses were brought, to corroborate the unfounded allegations that were made against me”—and he was right that none had, at any rate from outside the council itself (Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 15 June 1899). He also claimed that his own refutations had been “uniformly suppressed” and that a letter from the Guild’s trustees objecting to his dismissal was not laid before the council. He condemned as “an infamous fabrication” the claim of the Lord Mayor (W. E. Clegg, a notable man of law) that White had insulted members of the committee on no fewer than four occasions, pointing out that no such allegations had ever been brought to the RMC, a fact which is corroborated by the minutes (Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 15 June 1899).

White claimed that he could muster hundreds of witnesses as to his good character. As to “the invasion of my residence”, he said, “had the two members of the committee concerned made the necessary apology that was due to me instead of, as they consider, from me [to them], such inventions in support of their behaviour and attitude towards me would not have been made”.

Denouncing the “utterly false and absurd statements”, he continued to burn his bridges:

“Such calamnious [sic] statements having been publicly made respecting me, I shall be glad if you will read this, as a refutation, of the baseless charges that have been brought against me by those who have no intimate knowledge, either of myself or my work.”

The newspaper noted that in fact the letter was not read at the meeting. White concluded, poignantly and angrily:

“The resignation of the office which I have loyally and dutifully fulfilled for nine and a half years, with, I may say, much personal discomfort and private expense, is a small matter in comparison with the enormity of the malice, and the ingratitude with which my endeavours and work in the interest of this unique museum have been meted out as my reward: and it is now in the cause of honour and justice alone that I demand the hearing that has hitherto been denied me.”

His plea fell on deaf ears. In the end, White’s sacking had come about because he was difficult to work with. The controversy was also a symptom of the antagonisms inherent in the unstable relationship between a museum building (owned and staffed by the municipal authorities) and a collection (that was, and would only ever be, on loan to Sheffield). The sense of insecurity that these arrangements fostered in the city were fed by haunting memories of the tortured years of negotiation with Ruskin himself during the Walkley years, which were characterised by a constant quest for larger and more accessible museum premises. These tensions were manifested in the unequal composition of the Ruskin Museum Committee which was dominated by Sheffield Corporation, but which also had to accommodate the views of the Guild’s representatives.

But White’s defeat was a double victory for Sheffield City Council. From now on, the Guild would be marginalised. The Sheffield authorities had effectively incorporated the Ruskin Museum.

If the move from Walkley to Meersbrook in 1890 could not erase unhappy memories and resolve every problem, it did at least mark a new beginning. A great deal was achieved in the 1890s thanks largely to William White and his combination of dedication, knowledge, skill, and generosity. Firm foundations were laid for the years ahead,

The unhappy and controversial sacking of White as curator threatened to be deeply damaging to the Ruskin Museum. “Fiat Justicia” passed a devastating and ultimately unjustified verdict in the Sheffield Daily Telegraph, with which White nevertheless almost certainly agreed::

“The affair shows the disadvantage of placing an institution for high artistic culture here. The proper locality could be an intellectual or university centre where treasures of this sort would be appreciated. If at a commercial centre, the management should be under those who are interested in the subject, with, in case of contribution from public funds, members of the Council to look after the interests of ratepayers […]” (24 May 1899).

Half a century on, this view gained traction, and the collection was moved to the University of Reading. But, by some measure of fors, and of Ruskinian justice, it returned to Sheffield in the 1980s. The early verdict of the Sheffield Daily Telegraph was ultimately the right one:

“In its regenerated form the Ruskin Museum is of great gain to Sheffield, a fount of art from which it is hoped toilers of the town will derive some inspiration which will deepen their reverence for natural beauty. They have, to use the words of their benefactor, a ‘definite edifice, perfect instrument, and favourable circumstance’ in the Meersbrook Museum, and they will be wise if they use it aright” (16 April 1890).

LIFE AFTER SHEFFIELD

There was no way back for William White. His life following his dismissal from the curatorship of the Ruskin Museum does not appear to have been chronicled by Ruskin scholars hitherto. Part of the reason for that is that White moved back to London and lived in relative obscurity. He did not quite sever all ties with the Ruskin world. As we have seen, on the publication of his article for the Magazine of Art about the illuminated birthday address to Ruskin that he had been so instrumental in bringing to fruition, he sent a copy to the Ruskin Museum. According to Ruskin’s editors, E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn, White also co-operated with the production of the 30th volume of the Library Edition of Ruskin’s Works, a tome dedicated to the Guild of St George. White had “very kindly placed” at Cook’s disposal “much manuscript material in addition to his printed catalogues, and in other ways has rendered valuable assistance in the preparation of this volume” (Ruskin, Works, 30.xliv). It would, one suspects, be going too far to say there were no hard feelings, but they did not extend to Ruskin or Ruskin scholarship.

Described on his death certificate as a retired art critic, he seems to have made a career from writing scholarly articles, mostly about the work of Turner. By 1901, he and his wife were living in Lambeth, and he described himself on his census return as an “Author”. He certainly published short articles on Turner in The Connoisseur (see, e.g., William White, “New Leaves in Turner’s Life: A Rejoinder” in The Connoisseur, vol. 16 (September 1906), pp. 47-50; and “Further Evidence” (December 1916) pp. 251-252). He seems to have worked for a while as a merchant, though what his line of business was remains obscure.

In November 1910, a 1,700-word letter appeared in the Burlington Magazine, addressing “The Turner Bequest. The Repudiated Authenticity of Drawings in the National Gallery”—a critique of A Complete Inventory of the Drawings of the Turner Bequest (1909) commissioned by the National Gallery’s trustees from the art critic and journalist, A. J. Finberg (1866-1939). Completing work started by Ruskin, Finberg’s work became the standard guide to Turner’s works on paper bequeathed by the artist to the nation. As well as questioning several of Finberg’s judgements, and querying his justification for them, he pointed out many errors in transcription and identification (see The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, vol. 18, no. 92 (November 1910), pp. 120-122). Shortly afterwards, White presented some copperplates of Turner to the British Museum (see e.g. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1911-0119-2).

White seems to have done well enough in business—or perhaps retained a sufficient portion of his inheritance—to occupy an 11-room house in West Dulwich by 1911, not far from his childhood home in Morden. He was by then 55 and retired, and he and his wife enjoyed the help of two domestic servants. By 1916 the couple had moved to 5, Bromley Grove in Shortlands, Kent: they named their 11-roomed home “Norton Leas”, presumably a conscious allusion to the district in which the Ruskin Museum was located, suggesting that by then White had come to terms with the bitter experience of his dismissal.

On 27 November that year he once again intervened in debates about the Turner Bequest, writing a letter that appeared in the Daily Telegraph.

William White died on Christmas Day 1932 of pulmonary tuberculosis. His wife and a nephew were by his side. He had made a deathbed will the previous day (which was also the anniversary of his parents’ wedding). His estate was valued at £4,579 (more than £200k today). His widow, Hester, left her estate to a niece, Florence Ellen Lean. She died in Ealing in 1950.

Send feedback to contact@stuarteagles.co.uk