Celebrating Paul Dawson

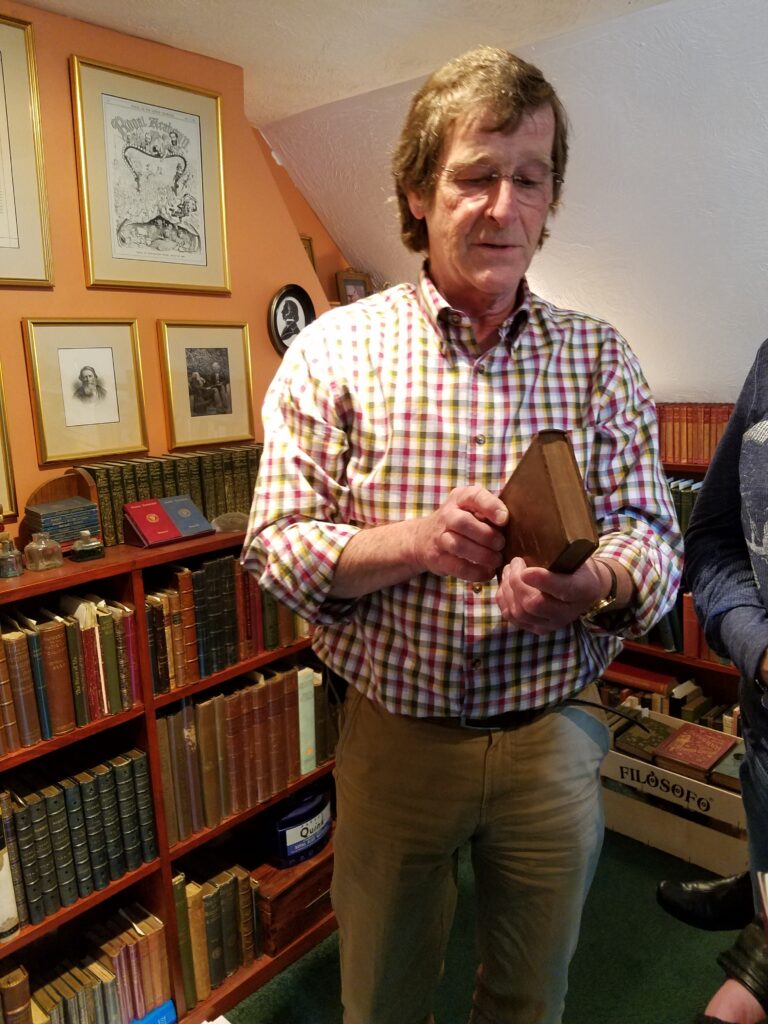

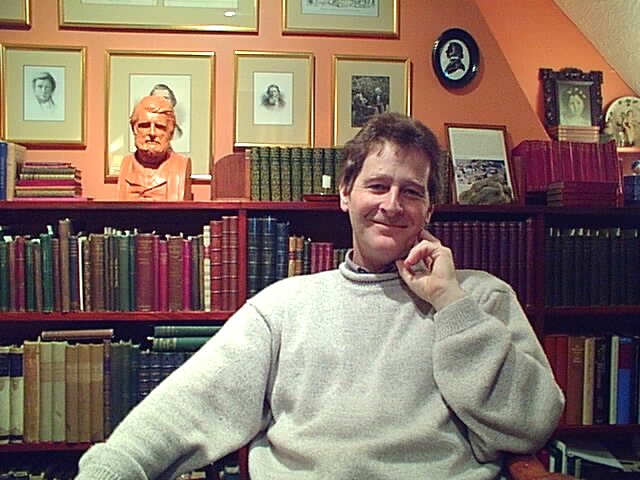

Paul Dawson sharing his wide knowledge and boundless enthusiasm in his study.

The strength of any Friends organisation relies heavily on the hard work and dedication of its volunteer committee. The modern-day Friends of Ruskin’s Brantwood was founded 35 years ago. It produced its first newsletter within about six months of its inception. For the past 25 years its twice-yearly publication has been edited with considerable flair and entirely without fuss by Paul Dawson, a Ruskin scholar and collector of great distinction, who has been the backbone of the Friends throughout his involvement. Or perhaps that should be the funny bone, for Paul is always ready with a joke, breaking into a smile with laughter in his eyes.

Such a milestone anniversary, marking a quarter-of-a-century of unstinting editorial service, demands not merely acknowledgement and thanks, but recognition and celebration. As such, I have asked a small but select group of Friends to weigh Paul’s achievements. I have not, however, approached anyone either on the current staff of Brantwood or the committee of the Friends: this blog is strictly unofficial. The contributions curated here are are drawn from both the UK and the US—some of the messages come from more recent recruits to the Ruskin fold, while others are from those of longer standing.

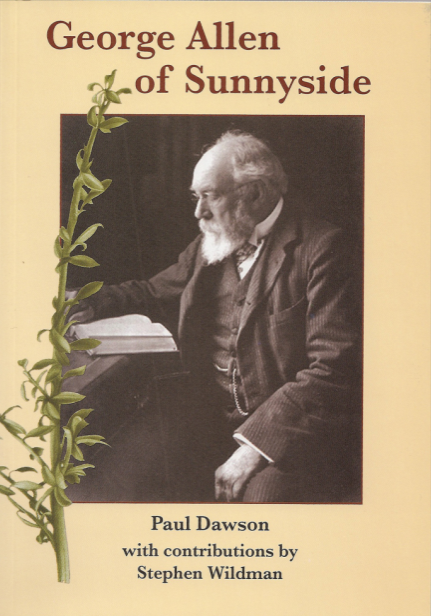

Paul’s Ruskinian activities go far beyond his work on the newsletter and, inevitably and rightly, some of them have been touched upon. I would myself like to note of his recent term as the Chairman of the Friends, a role in which his determination and diplomacy have paid dividends. His scholarly output has been wide-ranging, and always well-researched and engagingly written. Most notable is his exceptionally well-informed and detailed understanding of the life of Ruskin’s friend and publisher, George Allen, whose story he tells in an accessible but sensitively nuanced way. Paul is also a discerning collector of Ruskiniana who has so frequently shared his cultural granary with others, be they unknown undergraduates or fellow authors.

Yet perhaps Paul’s most consequential role over the years has been an unofficial one, as a sort of Ruskinian ambassador who has enthusiastically shared his knowledge and passion with a wide variety of individuals and groups—from literary enthusiasts in Kent and in his home county of Sussex, to students in the American state of Arkansas, and from eager audiences of Ruskinians at Brantwood, to Arts and Crafts practitioners and historians in Roycroft. He has done so by means of talks, exhibitions and guided tours, as well as in his many articles and books. What unites all of his admirable endeavours is his extraordinary generosity. He always gives freely and patiently of his time and expertise. Time and time again he has provided proof of his enduring love of Ruskin and his world.

A measure of Paul’s achievement is afforded by the fact that, in his time as editor for the Friends, he has transformed the newsletter from a few stapled, photocopied sheets to a professionally printed magazine. In Autumn 2013, it was regenerated into a new saddle-stitched format, with an eye-catching cover in full colour. Then, in Spring 2023, it was re-imagined as the Journal, a title that reflects its ever-growing status as a glossy, colour periodical filled with high-quality articles and images from contributors around the globe, all in an attractive, perfect (glued) binding. An archive of the magazine in PDF format is one of the rich online resource that has been made available to Friends. Paul also personally produced a list of all the articles to appear in the periodical’s first 25 years.

Ideal editors have an eye for quality. They are open-minded enough to welcome new contributors, and also sufficiently discerning to value returning ones. They marshal the regular columns, features, and news, and balance them with articles exploring the unfamiliar, sharing groundbreaking research, or articulating fresh points-of-view—sometimes all three together. Wherever necessary, they gently encourage and facilitate the judicious revision of submissions. They ensure that words are matched by appropriately striking illustrations. Paul Dawson excels at all of these things and that is a very rare thing.

Like the consummate tightrope-walker, he never puts a foot wrong. Furthermore, with an ever-replenishing treasury of his own rich material from which to share, he has in all modesty filled unwanted or unexpected gaps himself, and has also contributed many memorable main features over the years. To have consistently produced magazines of such high quality and enduring value, and to have done so on schedule, is as remarkable as it is impressive.

Other contributors to today’s blog will consider a range of Paul’s many qualities, though inevitably their combined explorations are far from exhaustive. For my part, I have merely scratched the surface, but I’ll conclude by saying how immensely courteous, considerate, and encouraging he has always been to me personally. In his quiet and unassuming way, he has always been mindful of my severe visual impairment. As such, he has helpfully given me lifts in his car to spare me the difficulties posed by public transport, and has read out-loud to me exhibition display boards.

Stuart Eagles and Paul Dawson at Beaucastle, Bewdley, 2016.

But he has gone much further than that. In recent years, as my eyesight has faded further, he has sent me a specially adapted copy of the Friends’ Journal with its visual content verbally described. Constitutionally incapable of accepting lavish praise for such amazing generosity and thoughtfulness, he tells me simply that he enjoys the process and that it’s a useful exercise for him. Such modesty about his unflagging and extraordinary kindness is entirely characteristic of the man, as anyone who knows him will recognise.

In celebrating Paul Dawson I do not merely put on record the indebted thanks and sincere appreciation of a professional colleague, but express the heartfelt admiration of a friend: it is long overdue.

*****

Prof. Stephen Wildman, retired Director of the Ruskin Library, Lancaster University

Over the last 30 years, Paul Dawson has been one of the stalwarts who have helped to maintain an interest in Ruskin, both as long-serving editor of the Journal (formerly Newsletter) of the Friends of Ruskin’s Brantwood and as the author of a series of useful and beautifully produced monographs. With a background in the printing trade, it was a miracle of serendipity that he should discover, in a Dorset bookshop, the remaining archive of George Allen, Ruskin’s publisher. This gave rise to one of his first contributions to the Newsletter in 1995, “Travels with a suitcase”.

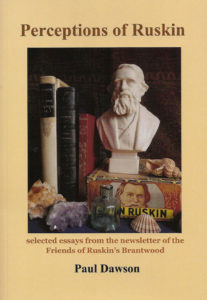

The more authoritative and exhaustive biographies, such as Tim Hilton’s, often contain useful information on the myriad facets of the life and work of a polymath such as Ruskin, but they still leave almost infinite scope for further examination and revelation. The late Jim Dearden, delighted to have known and worked with John Howard Whitehouse, who as a young man met Ruskin, was the doyen of such research and Paul has continued to add to the literature in a similar vein. Articles on “John Ruskin, Fulking and the Water Supply”, “Ruskin’s View, Kirkby Lonsdale” and the Ambleside Library and Book Club are among many items from the Friends’ newsletters later reprinted, with additions, in Perceptions of Ruskin (2017), characteristically offered to benefit Brantwood.

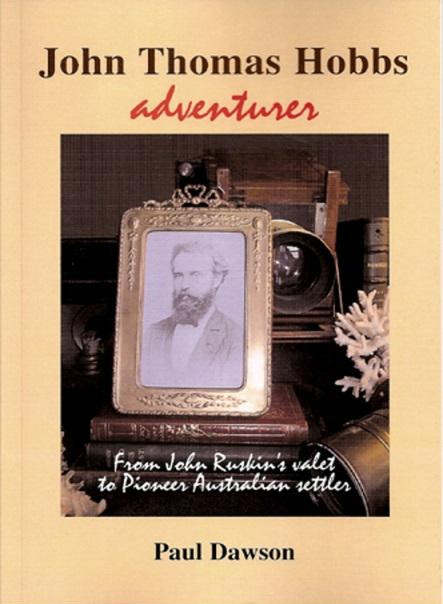

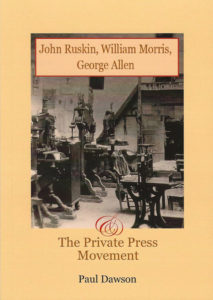

Perceptions is one of the neat and elegant little books published under the imprint of the Oxenbridge Press, putting Paul’s home village of Etchingham, just over the Kent border in Sussex, on the bibliographical map. The People’s Ruskin: The George Allen Editions of the Reprinted Works of John Ruskin (1999) is an essential guide to the Ruskin “greens”, its format reproduced, with Paul’s assistance, for the Ruskin Library’s centenary commemorative exhibition George Allen of Sunnyside (2007). To the same design is his monograph on John Thomas Hobbs, adventurer (2011) and his collaboration with Annie Creswick Dawson, an appreciation of her great-grandfather the sculptor and Ruskin protégé Benjamin Creswick (Guild of St George, 2015). Not far from George Allen’s house at Sunnyside, sadly no longer standing, Paul has made efforts to remind Orpington of one of its most celebrated former inhabitants.

Happily, this is not an obituary. A talk given to the American Chapter of the Guild of St George and the Roycroft Print Shop in 2019, Ruskin’s bicentenary year (John Ruskin, William Morris, George Allen and The Private Press Movement), gives every indication that Paul will continue writing and talking about Ruskin, perhaps even—on occasion—at Brantwood, a trek made so often without complaint.

*****

Annie Creswick Dawson, artist, and co-author (with Paul Dawson) of Benjamin Creswick

Editing the Brantwood Newsletter/Journal is a particularly complex task, drawing together reports on Ruskin’s beloved home (the house and the glorious gardens, the lake and surrounding scenery), and news from the local community, the estate’s volunteers, visitors, the Director, and the House Team—the list seems to be endlessly expanding. This is supplemented with research on Ruskin’s ever wider and ongoing influence, thoughtfully encouraged by the editor, Paul Dawson, whose insightful stewardship of such complexity produces such a richly interesting, well-balanced publication. He combines delight for the eye with up-to-date information on exhibitions, events, courses, and all manner of food-for-thought. He encourages and inspires continuing study with articles exploring unfamiliar aspects of Ruskin’s life and legacy.

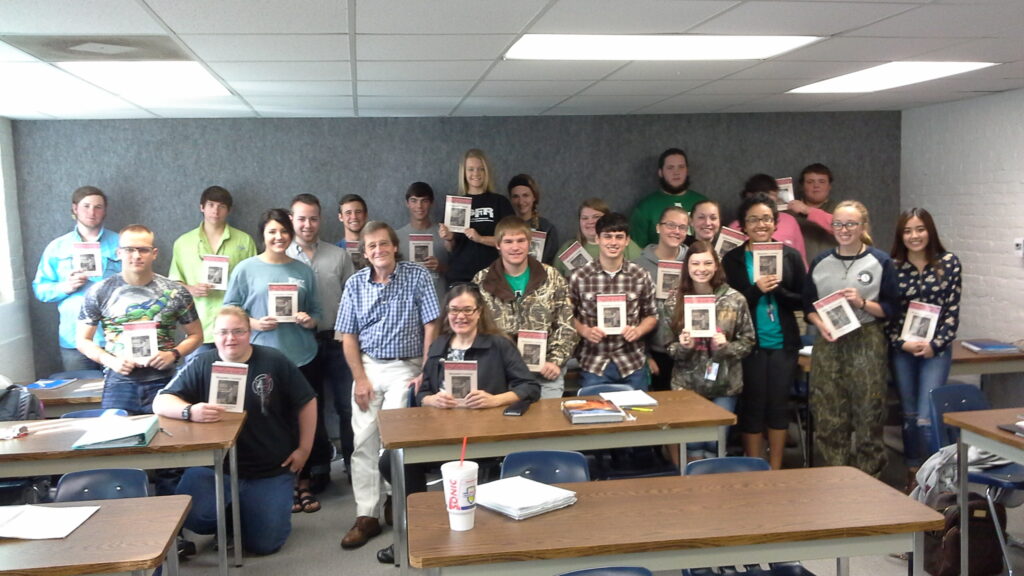

Members of Dr Kay Walter’s English class at UAM, holding the book, “Benjamin Creswick” by Annie Creswick Dawson (with Paul Dawson) (2016)

The Friends of Brantwood are fortunate to have an editor whose own excellent and extensive Ruskin studies are widely recognised, and who can calm and encourage writers and gather extensive material into a harmonious, beautifully balanced and thought-provoking publication twice a year—a real labour of love and dedication.

I know I am not alone when giving our Editor so many heartfelt thanks for so much pleasure and so great an expansion of my knowledge and love of Brantwood and Ruskin.

Stuart Eagles, Annie Creswick Dawson, and Paul Dawson, on Broad Street, Oxford (2015)

*****

Michele L. Burford, a prominent contributor of articles to recent issues of the Friends of Brantwood Newsletter and Journal

I was pleased to be asked by Dr Stuart Eagles to contribute to an appreciation of Paul Dawson, in gratitude for his quarter-of-a-century editing the Friends of Ruskin’s Brantwood Newsletter, now Journal.

I was introduced to Paul some years ago by David Hearn, who lives close by to him. Knowing my enthusiasm for all things Ruskin, David encouraged me to join the Friends.

I did so and received the bi-annual newsletter expertly edited by Paul. What a pleasure it was, a truly professional large format magazine, with a variety of Ruskin and Brantwood-related articles suiting all interests, including news, book reviews, articles, wonderful photographs and other illustrations. All were thoroughly researched, and enthusiastically written by numerous contributors, and beautifully pieced together by Paul.

I immediately wanted to contribute to this publication and spoke with Paul about some of my ideas, many of which have now been developed into articles and published. He is such a pleasant and thoughtful person to speak with and always engaging and encouraging.

Paul was persuaded to take up the position as chairman of the Friends in 2016 and each year would make the long return drive up to Brantwood from Sussex for the AGM, until his resignation last year. A fair and well-liked chairman with a great sense of humour, he was popular with the staff of Brantwood and the volunteers alike.

Paul has written and co-written numerous books which are an invaluable source both to researchers today and to those of the future.

In addition to his Ruskin and associated interests, his knowledge of the Victorian publisher, George Allen, is second to none, and I am still hoping—along, I am sure, with many others—that he will, in the not-too-distant future, succeed in publishing his long-awaited biography of Allen.

*****

Mike Salts, former long-time Friends’ committee member and librarian for its collection of books by and about Ruskin

Having known Paul for a very long time, probably more than 30 years, I can safely say that he is the perfect friend and correspondent. Whenever he came to Coniston for a Friends’ meeting, he always visited us at our home there and we enjoyed rich fellowship together.

It is impossible to overstate the importance of Paul’s contribution to the Friends’ newsletter and journal over the 25 years of his editorship. The publication has been a vital communication tool for the Friends, without which the organisation could hardly have been sustained. We can only guess the value of such communication to the ongoing life of Ruskin’s Brantwood. I, for one, feel deeply indebted to Paul for his sustained input and diligence.

Paul Dawson in his study (Photo: Mike Salts)

*****

Dr Kay Walter, professor of English in the School of Arts and Humanities, University of Arkansas at Monticello

I first met Paul Dawson through words. I’ve been a member of the Friends of Ruskin’s Brantwood since the early 1990s, and I purchased my life-membership before the millennial shift. From the depths of rural Arkansas, the connection to Brantwood and the study of John Ruskin seemed vague, ethereal, and remote. I read the newsletter but it was filled with names and places I didn’t know. I loved to read Ruskin, loved to teach my students about his ideas. This vague acquaintance would focus and clarify in 2010.

My mentor, Phillip Anderson, invited me to join him and Jay Curlin in proposing a Ruskin session at the Arkansas Philological Association. “You like Arthuriana,” he said. “Write about Ruskin and Chivalry.” Earlier that year, I had been to England, and at Blackwell’s I purchased a first edition of Hortus Inclusus. When I read it, I fell in love with Ruskin in a new way. He was not just the prophet, genius, and professor of Unto this Last, “The Storm Cloud of the Nineteenth Century,” and Sesame and Lilies, but he was also the neighbour, friend, and champion of the Beever sisters. This new view of Ruskin was the starting point of a paper I produced.

Our Ruskin session at the conference drew an oversized crowd, and all three papers meshed neatly and were roundly applauded. I honestly felt it was the best thing I’d ever written, perhaps even publishable, so I let it sit, waiting for the right opportunity to share it more widely. One day, while I was reading the Brantwood Newsletter, I found Paul Dawson’s email address and sent him a first tentative message, saying, “I have written an article […] that I would like to submit for your consideration. […] As all publications matter for professional advancement, I have [been] wrestling with ideas about where to submit it, but I cannot turn my heart from our newsletter as my first choice.”

My article, “Chivalry in John Ruskin” was approved for the Autumn 2013 issue, and I was encouraged when Paul wrote to say, “I have finished my preparation for the newsletter, and will have a brief editorial meeting next Saturday. […] This will be our first edition in the slightly revised format. […] Your piece looks good and reads so very well and I know it will be appreciated.” Our acquaintance developed through email messages, and when I found four young ladies who dreamed of travel to England as an essential part of their education, I created a travel seminar on Ruskin. As soon as I received official word of approval, I wrote to Paul.

I did not know him in any direct way, and when he asked for a detailed schedule, I was reluctant to share the itinerary of a woman accompanied by four young charges who had never been abroad. I spoke in vague terms to Paul about a week of Shakespeare studies, another in 1066 Country, and a visit to the Lakes to see Brantwood. Paul’s response was a bright and eager offer to welcome us. I offered to buy him a cup of tea if he would speak with my students. His reply was to invite my students and I to a carvery lunch, to open his home to show us his Ruskin library, and to allow the youngsters to use his home phone plan to make free calls to check in with their parents. He told me, further, that Annie Creswick Dawson would be with him to consider proofs for her then-forthcoming book about her great grandfather, Benjamin Creswick, and his connection to Ruskin.

My students and I found our way to Burwash where we met Paul and Annie at Batemans. We lunched at The Bear Inn for our first truly English meal. We followed them to Etchingham and gathered in the garden to hear Annie’s story. My young scholars were enchanted. They phoned their parents with breathless tales of wonder. Annie gave us each a copy of the picture her family treasures as a gift from Ruskin himself. All too soon, we left with hugs from new friends and promises to stay in touch and visit again.

Paul (standing) addressing Annie Creswick Dawson and The Kittens

Conversations about Ruskin, his ideas, and new friends continued long after we were gone. My students and I went on to Stratford-upon-Avon, and Annie and Paul talked about me and the charming young women they called The Kittens. I am told that their conversation quickly turned to proposing my Companionship in the Guild of St George, and when Paul emailed me to ask if I’d ever considered it, I thought he was joking.

I’d heard of the Guild, and I’d regretted many times the impossibility of my being part of such an esteemed group. “Why,” I thought, “would the Guild want me?” I had no wealth but life, no fame but my local reputation as a Ruskin enthusiast to offer. Paul wasn’t easily dissuaded, though, and soon he was writing to Stuart Eagles and Clive Wilmer to introduce me. In 2015 I found myself in Sheffield signing my name on the Roll of Companions.

Because Paul Dawson was willing to edit the Friends of Ruskin’s Brantwood Journal, I was able to publish my first important scholarship on Ruskin. As a result, I was awarded a promotion and received tenure at my university. Through Paul, I have been able to introduce my students and their ideas to the Ruskin community. Because of Paul, I am a Companion of the Guild and through my connections there I am a life-member of the Ruskin Art Club, a board member of the Ruskin Society of North America, a member of The Ruskin Society, and a rich person for the network of Ruskin friends I’ve made. For a kid from southeastern Arkansas like me, the future looks promising because a friendship blossomed from words.

Paul Dawson addressing students at UAM.

Paul Dawson addressing students at UAM.

*****

Three of Dr Walter’s former students have also written to pay tribute to Paul.

Caleb Hayes

Paul Dawson’s influence on my education is both transformative and enduring. Before we met, his collaboration with Annie Creswick Dawson in chronicling her great-grandfather’s legacy had already shaped my burgeoning love for Ruskinian ideals. Together, through the teachings of Dr. Kay Walter, they introduced me to a rich intellectual tradition that awakened a deeper appreciation for literature and a yearning for the values John Ruskin extolled.

A consummate guide and educator, Paul extended gracious hospitality early on by inviting us into his home. In addition to tea, he shared his collection of Ruskin’s works, fostering thoughtful conversation and illuminating his depth of knowledge and dedication to our learning. His passion translated into action when he arranged a service-learning opportunity at Ruskin’s Brantwood, where we worked alongside the groundskeepers, crafting plant supports from birch in the Professor’s garden and clearing the shoreline of Coniston Water. This experience brought Ruskin’s philosophy to life, blending the harmony of nature and craftsmanship in a profoundly tangible way.

Acting as a bridge to the wider Ruskinian community, Paul introduced us to figures like Annie Creswick Dawson and Stuart Eagles, who in turn imparted their knowledge and wisdom in leading us through the streets of Oxford, sharing stories of Ruskin’s influence at every turn—from the buildings in which he lectured, and the colleges with which he was association, to the very stones of the city’s natural history museum.

Yet, perhaps Paul’s greatest lessons were to be found in his quiet acts of service, such as assisting in the laundry of weary college travellers or arranging a pre-dawn bus transfer to ensure our safe passage to Venice—a trip he wasn’t even set to go on. These moments spoke volumes about his generosity and humility.

If, as Ruskin wrote, “there is no wealth but life,” then, by every metric, Paul Dawson holds immeasurable wealth of spirit.

*****

Merrell E. Miles Westerman

When I think of Paul Dawson, my mind does not immediately go to the dedicated Ruskin expert, accomplished author, and international speaker, though those descriptors absolutely apply and have been earned many times over.

Instead, when I initially think of Paul Dawson, I see a man sitting on an armchair reading aloud the work of Shel Silverstein as an international point of connection through the arts.

Merrelll with Dr Kay Walter and Paul Dawson

I think of glass bottles of ginger beer and lemonade—beverages which he did not plan to drink, but instead had acquired for the group of young, American scholars who would be learning from him.

I think of the light in his attentive eyes as the young scholars recited poetry over tea and pastries.

I think of his words of affirmation and encouragement.

I think of the gentleman who attended my wedding ceremony in rural Arkansas, despite the fact that he resides at least 4,000 miles away from my home.

When I continue to think of Paul Dawson, I marvel at both the power and impact of a dedicated keeper of literary history.

I notice the evidence of his success—the culmination of sustained interest, disciplined observation, applied passion, and strategic storytelling.

I think about the Arts and Crafts movement, a collective stance of defiance against the industrial revolution and a move towards honuoring the capacity of people to make beautiful things in a studious, skilled, slow, safe, and uniquely human way.

I think of how Paul Dawson’s acts of information-gathering, record-keeping, and story-telling (both written and oral) made John Ruskin come alive for me over 100 years after Ruskin’s death.

When I think of Paul Dawson, I think of a guided tour of John Ruskin’s Brantwood.

I think of the intimate opportunity to meet Annie Creswick Dawson that he arranged.

When I think of Paul Dawson, I consider how the air is charged around people who are truly passionate about, and connected with, something bigger than themselves. Paul Dawson is one of those people. He carries a current through his life, his work, and his life’s-work, and in a uniquely skilled and powerfully human way, he connects, sharing that current with others.

I will forever be grateful to have been a witness to all this, to have learned from him, and to carry the energy he has shared into my own life and work. I am forever grateful to have been infused with the Ruskin spark, courtesy of Paul Dawson.

*****

Bradem Taylor

I first met Paul Dawson in the spring of 2018. My freshman composition professor, Dr Kay Walter, had invited Paul to speak to my class about John Ruskin. Before the class began, she asked me to go and sit beside him and introduce myself. I had the opportunity to talk to him at the beginning of class and afterwards. There, our friendship started. Over the next week I got to talk to Paul a lot about what I was studying and where I hoped my studies would take me. Paul was very kind with his words and encouraged me to continue my research regarding working-class people and to continue to speak to others about what I found interesting.

After Paul left the United States, we kept in touch. I would email Paul with Ruskin-related questions and eventually even questions not related to Ruskin. What I found most fun and interesting to talk with him about was the George Allen “greens”. I have been collecting these books (typically in green boards and published by Allen). In my pursuit of completing my collection, Paul became an invaluable resource. He was even gracious enough to send me Ruskin books as a gift when I graduated from the University of Arkansas at Monticello.

Paul was not only willing to talk to me when I asked, but he was happy to entertain my research. The Friends of Ruskin’s Brantwood Journal was the first place that I was published and got to share my ideas with the world. For that, I will forever be indebted to him.