In the first of a new series of occasional blogs exploring Ruskin’s global reach, I focus on how Ruskin was celebrated as an Apostle of Beauty calling on Europe to reject modern industrial capitalism and return to nature. A brief look at two Czech readers of Ruskin takes us, via the American Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862), to North Holland and one of Ruskin’s keenest Dutch champions. I dedicate this post to Prof. Emma Sdegno, friend, Ruskin scholar, and the person who generously invited me to explore some of these topics in the recently issued collection of cross-cultural essays, John Ruskin’s Europe, published by Ca’ Foscari University, Venice.

Let’s start with an image likely to be unfamiliar to almost every Ruskin scholar.

This depiction of Ruskin as a Czech peasant might not look much like the man himself, but it epitomizes a form of European reception around of the turn of the nineteenth century into the twentieth. Many Europeans, often influenced by the French critic Robert de la Sizeranne (1866-1932), saw Ruskin as the Apostle of Beauty and the Father of the Arts and Crafts Movement. His central message, they thought, was that we should reject the ugly industrial city and return to a simpler life in the beautiful, unspoiled countryside in which most of us would be sustained by the work of our hands. The drawing is by the Czech artist Jan Priesler (1872-1918). It appeared in 1900 at the head of an article about Ruskin by the Czech journalist, essayist and author, Gustav Jaroš (1867-1948), who wrote under his pseudonym Gamma in the influential journal, Volné Sméry (Free Directions). For a long time Priesler was editor of the journal, and later worked as an art professor.

Miloš Seifert (1887-1941)

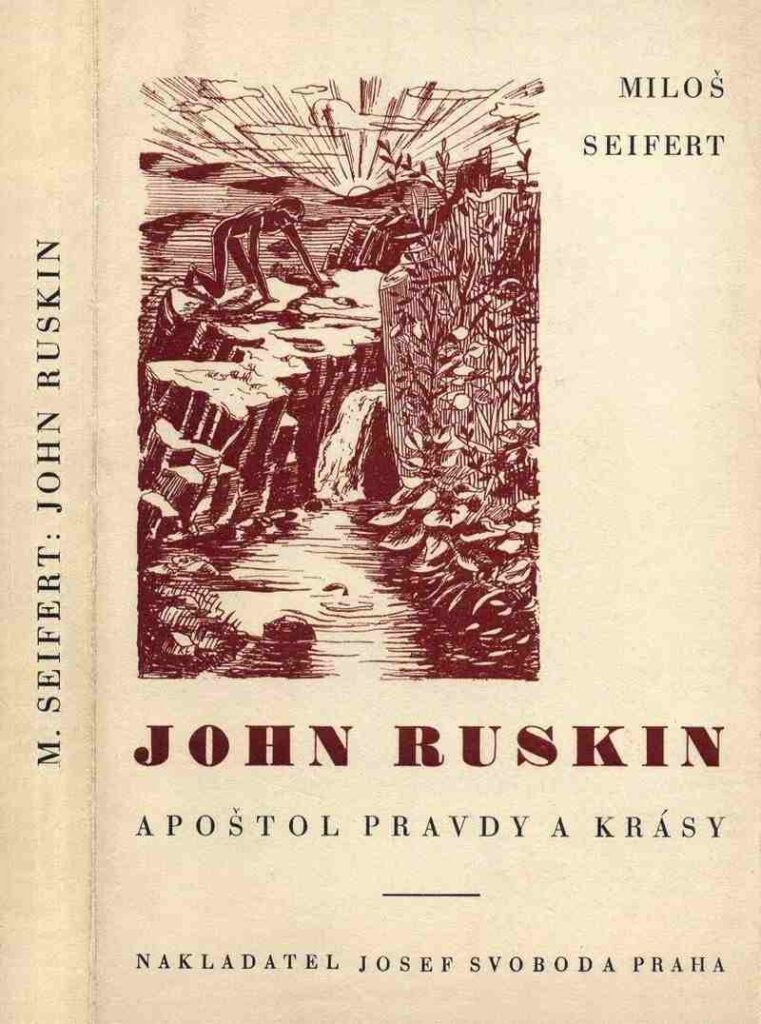

One of Ruskin’s most important Czech translators was Miloš Seifert, a school teacher, naturalist, writer, and translator. He maintained a life-long interest in Ruskin, and provides an unlikely but important link to Ruskin’s reception in the Netherlands. His 1937 study of Ruskin was entitled John Ruskin, apostol pravdy a krásy. Myslenky a dilo (John Ruskin, Apostle of Truth and Beauty. Ideas and Work). As a young man he had translated Unto this Last (1910).

(Cover art, above; title-page, below)

Miloš Seifert, (1937), John Ruskin, apostol pravdy a krásy. Myslenky a dilo (John Ruskin: Apostle of Truth and Beauty. Ideas and Work.) Prague: Josef Svoboda.

Seifert became the father of the Czech Woodcrafting Movement. He was, in common with many of Ruskin’s most ardent disciples around the world, a vegetarian, a pacifist, a campaigner for nature conservation, and an ecologist. Immediately prior to publishing his major study of Ruskin he wrote a monograph on Thoreau (1934). In large part it was inspired by his celebration of the canonical Dutch writer and psychiatrist, Frederik van Eeden (1922). Van Eeden had established the simple commune of artists and peasants near Bussum, in northern Holland, which had been inspired by his own love of Thoreau and Ruskin and which he called Walden.

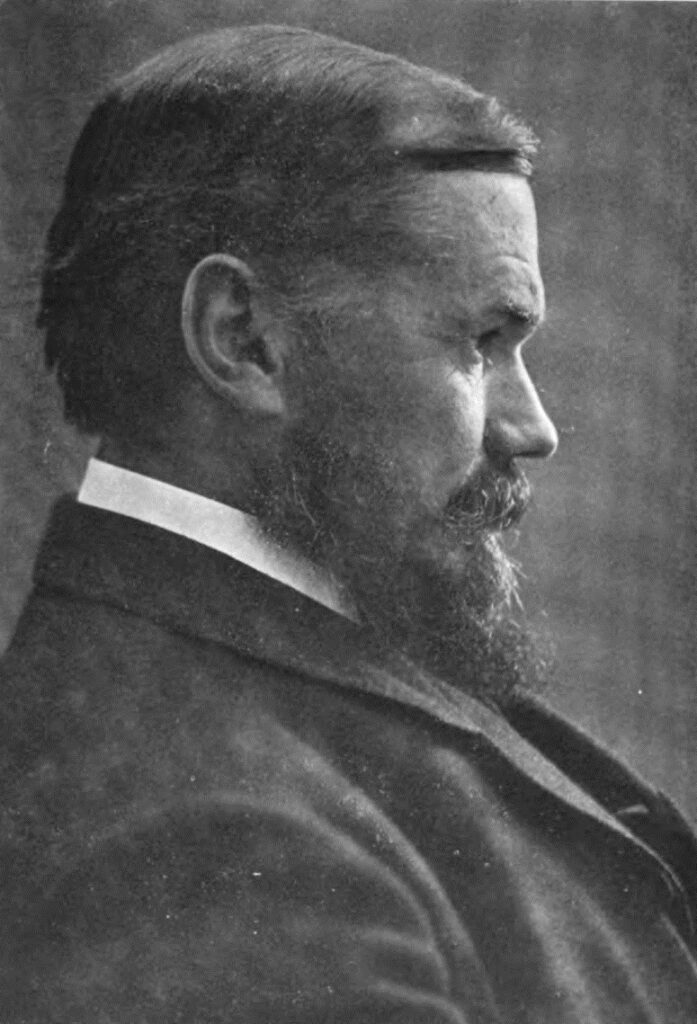

Frederik van Eeden (1860-1932)

Frederik van Eeden (1860-1932)

Frederik van Eeden is regarded as a canonical Dutch writer and psychiatrist, who had studied English at Leiden. He wrote a preface to the first volume of Bertha Koch-Huber’s great Dutch translation of Fors Clavigera. Verzameling van Brieven aan Werklieden (A Collection of Letters to Workmen) (1901).

Van Eeden visited Britain regularly from 1877. He often wrote in English and penned an English sonnet dedicated to Ruskin which was published in De Nieuwe Gids (The New Guide), a journal he helped to found and edit.

O splendid well of holy bitterness

brimful with thy dire sorrows and the shame

of this vile age — thou quenchest rage’s flame,

thou sweetenest my own chalice of distress.

Could thou but yet, ere mortal parting came,

my thanks accept, my poor endeavours bless

and hear my oath that I shall without blame

thy heavy standard bear and knightly dress.

Alas! for wrongs by blinded idlers spent

on thee, their prophet and their truest chief!

Thy great heart overcome, thy great mind bent

by weight of old and unrelenting grief!

Now dost thou die – and I who cannot mend!

And my full force that cannot give relief!

— Frederik van Eeden, ‘John Ruskin’

in De Niewe Gids (The New Guide),

vol. 5 (September 1899) [p. 4] (but not paginated).

Van Eeden wrote the sonnet in a ‘beautiful valley’ on Saturday, 10 September 1898 after reading some verses by Coleridge. He did not submit it for publication for another 11 months. He wrote in his diary that Ruskin was giving him ‘strength and comfort’ just as he was embarking on his own scathing attack on modern capitalism. His allusion in the sonnet to the Guild of St George is notable, and he regarded his own socialism as following in an anti-capitalist tradition typified by Ruskin.

Van Eeden’s foreword to the Dutch translation of Fors described it as ‘one of the great books of our time that one must read with full attention, meticulously and methodically’. Fors, he asserted, was the ‘expression of a rich, mature spirit which lithely moved in all realms of thought’. Ruskin’s thoughts, expressed in these unmethodical and impulsive letters were ‘held together by a deeper meaning’ that van Eeden held to be ‘always instructive and important’.

(Above and below)

(Above and below)

The Dutch translation of Fors Clavigera,

published 1901 and reissued 1918.

He particularly commended Ruskin’s economic philosophy, considering him ‘more scientific than the socialists’ despite a superficial tone that was ‘playful and whimsical’. Ruskin’s ‘brilliant play on words and terms’ (a technique van Eeden also deployed in his own writings) allowed him to avoid the traps fallen into by others. It enabled him to penetrate the true implications of commonly accepted concepts, and thereby to expose their relative nature and volatility.

He recommended the book to Dutch readers as especially relevant at his time of writing (February 1901). This, he said, was because Ruskin showed that, in contrast to the impression given by Dutch newspapers and magazines, socialism and communism could and should be noble, not vulgar, brutal, spiteful or narrowly materialist.

He recognised, however, that Ruskin did not advocate or approve of equality, that he was a royalist who believed in a hierarchical social structure, yet he maintained that Ruskin’s prophetic words earned him his place alongside Whitman and Thoreau. Ruskin refused to recognise ‘the poetry of the machine’ as Kropotkin called it, so deep was his rejection of modern industry—of ‘money, factories and trading’—expressed most powerfully as a haunting lament to the darkening of England’s skies by coal-smoke. Ruskin, moreover, was ‘the most eloquent communist England had had’—in the sense, presumably, of his perceived advocacy through the Guild of St George of rural communities.

Van Eeden’s foreword to Fors was written in Walden, the simple commune of artists and peasants he named after Thoreau’s influential book of 1854. Van Eeden’s critical engagement with Ruskin was unquestionably coloured by his attempt to live a self-sufficient life in common with fellow communists. He believed in confronting the harsh realities of life. His personal motto was ‘Waar de mensheid is, en haar weedom, daar is mijn weg.’ (‘Where mankind is, and her woe, there is my path.’) Ruskin’s St George’s Guild had been unsuccessful, van Eeden thought, and although (an unrelated) prosperous Ruskin colony then endured in Tennessee, in England—he told readers—there was no equivalent, and Ruskin was associated with educational foundations not worthy of his name (though he does not spell out what he means by this and where he is thinking of).

Ruskin ought not to be seen thus, van Eeden insisted, because although Ruskin was an artist and a teacher, he recognised that certain basic conditions were necessary before a man could paint or a student could learn properly to ‘read’ a painting. This meant that one needed to put food first, ‘higher and more important interests’ coming only when ‘material existence [is] assured’, a reading of Ruskin that took van Eeden closer to Thoreau, Kropotkin and Tolstoy than to Ruskin himself. Any colony should proceed on this basis, or suffer the fate of Robert Owen’s New Harmony or Charles Fourier’s Phalanstère. St George’s Guild, he said, was both ‘a masterful plan and a glorious fiction’.

Fors had ‘great value as a moral document, as a standard of high morality’, he concluded, and contained practical strategies for colonies and colonists to follow. Although van Eeden himself continued to live at Walden, the last of his fellow colonists had left by 1907 and a colony he established, but never lived at, in North Carolina, USA (Van Eeden Colony) limped on until 1939. Van Eeden’s experiments went the way of almost all idealistic back-to-the-land colonies of radical simple-lifers: it drowned in the whirlpool of over-ambition and dissolved in the acid-bath of principled disputation and personal disagreement.

Van Eeden claimed that his own socialistic ideas had been worked out independently and he did not claim to be Ruskin’s disciple. But his affinity with Ruskin is notable. He once joked, ‘I have been much astonished to find that Ruskin had the impertinence to print my views long before I thought fit to maintain them’. It is remarkable how many influential men and women in Europe could have said the same, as we shall discover in blogs to come.

Please send feedback to contact@stuarteagles.co.uk