My forthcoming study of John Ruskin’s Sheffield will present the most complete biography yet published of Henry Swan (1825-1889) , the curator of St George’s Museum, Walkley. This blog post answers an important question: did Henry Swan help in the 1850s to decorate two of Oxford University’s most striking Victorian buildings?

In his detailed and beautifully illustrated study, The Pre-Raphaelites and Science (2018) Prof. John Holmes asserts that “the stylized decorative scheme for [Frederick William Hope’s] entomology museum” at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History was “prepared by Ruskin’s protégé Henry Swan” (121). He again attributes the painting of the “walls and ceiling” to Henry Swan in his latest book, The Temple of Science: The Pre-Raphaelites and the Oxford University Museum of Natural History (2020) (119). The same claim was made on 27 March 2018 in a news release about the museum’s “HOPE for the Future” project to reinvigorate the British Insect Collection and to restore its original home in the Pre-Raphaelite Westwood Room. The news release explains that the decoration by Henry Swan—a “follower of […] John Ruskin” who “led” in the design of the museum—

“features exquisitely painted wall borders, ceiling beams and entomological detailing, including a carved interpretation of stag beetle and hawkmoth life cycles on the stone fireplace.”

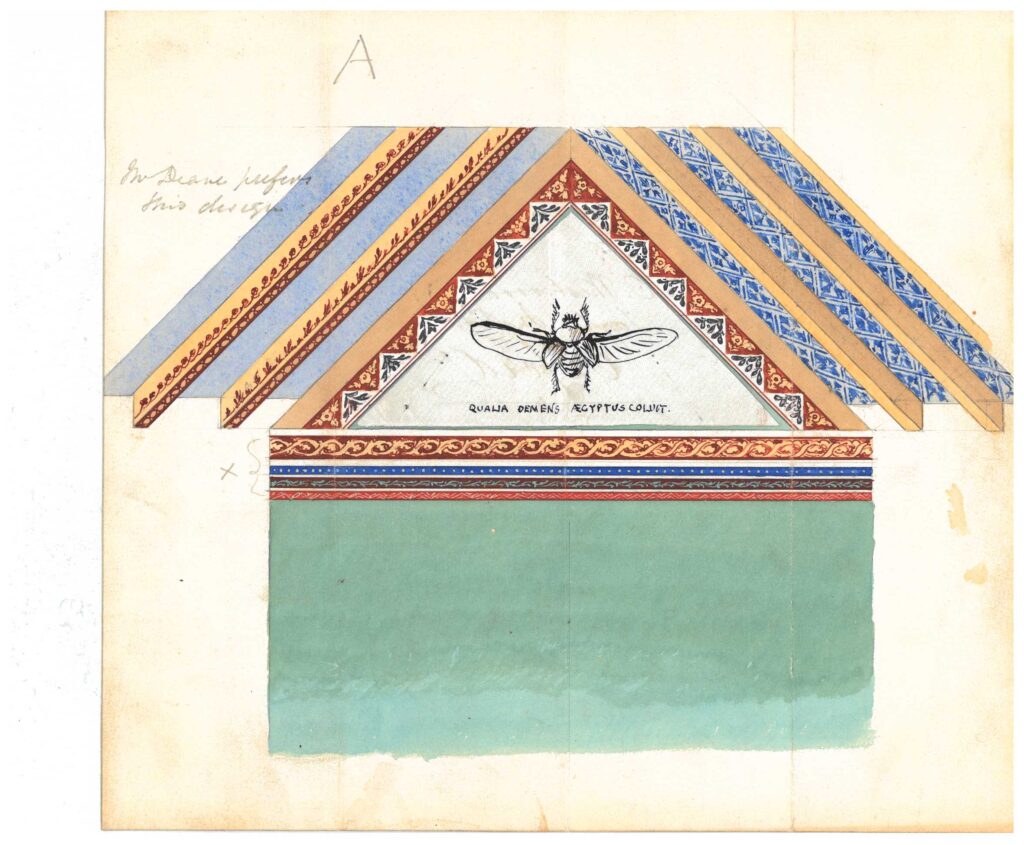

An unused design attributed to Mr Swan

© Oxford University Museum of Natural History

Holmes acknowledges in his 2018 study, however, that none of the references to Swan in contemporary documents and accounts reveal his first name, but he concludes that the man in question “is most likely the Henry Swan who studied under Ruskin at the Working Men’s College and went on to be the curator of the museum of [Ruskin’s] Guild of St George at Walkley in Sheffield in the 1870s and 1880s” (275 n33).

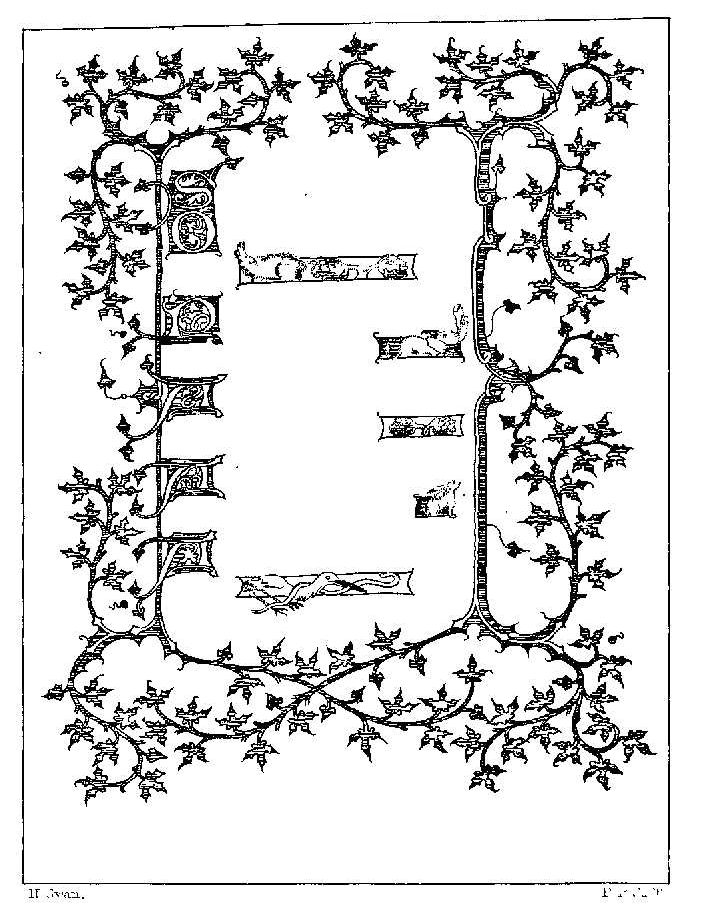

What is generally known of Henry Swan certainly makes him a plausible candidate. Swan attended Ruskin’s drawing classes at the Working Men’s College in Red Lion Square as soon as they began in 1854. He got to know the Master well, and Ruskin set him to work copying illuminated manuscripts. In a letter to Swan written in February 1855, Ruskin praised Swan’s “true eye for colour” in capturing a “depth and intensity” that he found “very delightful”.[1] Ruskin’s good opinion of Swan’s skill is demonstrated by the fact that Ruskin asked him to engrave a plate for the third volume of Modern Painters (1856)—an example of missal-painting of “Botany of the 14th Century”. Swan would also later engrave a plate for The Laws of Fesole (1877-78): “Construction for Placing the Honour-Points”.

“Botany of the 14th Century” engraved by Henry Swan for Ruskin’s Modern Painters III (1856)

Frederick O’Dwyer, in his magnificent history of the architecture of Deane and Woodward, the partnership responsible for the construction of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, cites a report in The Builder noting the progress made by “Mr Swan” with “abstract friezes and other wall decorations” (213). The periodical told readers:

“Around the Court are dispersed the lecture rooms, work room and private studies required in each department. Some of these have been decorated by Mr Swan, cleverly, but so roughly as to have a make-shift appearance which is not entirely pleasing.” (The Builder, vol. 17 (18 June 1859) 401.)

Qualified praise, to say the least. “The best piece of Mr Swan’s work” the report goes on “is in Mr Hope’s Museum”

“where the decorations, simple as they may be, show great life and variety. Even here, however, we must note that the diaper [i.e. pattern] would have been more praiseworthy if the lines had been upright.”

O’Dwyer explains that the scheme of decoration was referred by the relevant university committee to the architects, and a design in the museum’s archive, attributed to Swan though never used, has the words “Mr Deane prefers this design” written upon it (214) [see first image, above]. O’Dwyer explains that “Ruskin was equivocal about internal decoration” and felt that as much as he revered the use of colour matters of detail could be left to some future point (214). O’Dwyer adds that Ruskin even suggested that such decoration was unnecessary in an undated letter to his friend Henry Acland (1815-1900) who had recently been appointed Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford, and was crucial to the creation of the museum (see 214).

Neither The Builder nor O’Dwyer identifies Swan’s first name, though the latter refers to him parenthetically as “a friend of William Morris” (213). In an endnote, Holmes explains that in October and November 1857 Swan had worked with William Morris on the design of the ceiling at what was then the Debating Hall of the Oxford Union Society. This was the “jovial campaign”—as its moving spirit, Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) called it—to paint ten Pre-Raphaelite murals themed around Arthurian legend and to decorate the underside of the roof of what is now the library of the Oxford Union. Most famously it involved William Morris (1834-1896) and Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898), as well as Rossetti, though a host of others—including “Swan”—also contributed.

John Holmes states, without quoting them, that the evidence for Swan’s involvement in the Oxford Union work can be found in J. W. Mackail’s biography of Morris, and Georgiana Burne-Jones’s Memorials of her late husband (see Holmes 275 n33). No specific evidence is offered that the “Mr Swan” who worked on the Oxford University Museum and the Oxford Union decoration was one and the same, though Holmes points out that in common with Alexander Munro (1825-1871) and John Hungerford Pollen (1820-1902) “Swan” worked on both buildings. And both the Union and the Museum were, after all, the Ruskinian Gothic Revival creations of the Irish architects, Thomas Deane (1828-1899) and (especially) Benjamin Woodward (1803-1861).

One source that Holmes does not cite is William E. Fredeman’s edition of Rossetti’s correspondence, published in ten volumes. In the second of these, covering the period from 1855 to 1862 (and published in 2002), Fredeman anticipates Holmes’s identification of Henry Swan as “one of the assistants who worked with Morris on the ceiling” of the Oxford Union (2:258n), calling him the “likely” candidate (2:260n). He also cites Mackail and Burne-Jones in support of the claim. Rossetti refers to “Swan”—once again, no first name is given—in three letters written to Ford Madox Brown (1821-1893) in June 1859. Summarizing Henry Swan’s biography, Fredeman refers readers to the 39-volume Library Edition of Ruskin’s Works for further information (specifically to volume 30, xli-xlv), though it does not refer to any involvement by Swan in the decoration either of the Oxford Union or the Oxford University Museum. Fredeman’s identification of Henry Swan was accepted by Alison Chapman and Joanne Meacock in their useful reference work, A Rossetti Family Chronology (2007) (see e.g. 110).

Mackail’s biography of Morris makes for particularly interesting reading. He quotes from the diary of Cormell (“Crom”) Price (1836-1910), later headmaster of Haileybury and another of the young “campaigners” engaged in the decoration of the Union. Price recorded that on the evening of 30 October 1857, he and “Swan” were among a group of a dozen participants in the Union work which Morris treated to a reading of his “very grand” King Arthur’s Tomb and Lancelot and Guinevere (qtd Mackail, 1:126). Alexander Munro, Rossetti, Burne-Jones and John Roddam Spencer Stanhope (1829-1908) were also present. Price recorded that two days later, on 1 November, Swan was present with Burne-Jones and others when Morris first met Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837-1909) who was introduced to the group by Edwin Hatch (1835-1889) (see Mackail 1:127).

Mackail provides a useful description of Swan, claiming that he was “a friend of Rossetti’s and a man of some amount of genius which verged on eccentricity” (1:127). Both claims would appear to support the idea that the man in question was Henry Swan. First, as a pupil of Ruskin’s drawing classes, it is probable that Henry Swan met Rossetti because Rossetti assisted Ruskin’s college teaching. Second, most Ruskin scholars who have written about Henry Swan have underlined his eccentricity, with obituarists such as Hargrave claiming that he was a vegetarian and a Quaker who was among the first to introduce the bicycle into Britain and also attempted to popularize the throwing of the boomerang as an athletic exercise, though no concrete details have ever been discovered of the last two claims. In the 1840s he embraced the innovations in phonetic spelling and phonography pioneered by Isaac Pitman, and in the mid-1850s he devised an innovative educational scheme of musical notation. A few years later he invented a form of three-dimensional photography which did not require the use of a stereoscope and would occupy much of his energy in the 1860s. Such inventiveness is certainly susceptible to allegations of eccentricity.

Mackail explains that Swan

“had taken a considerable part in executing the decorations on the Union roof, his name, together with those of Morris, Faulkner, and St. John Tyrwhitt of Christ Church, being inscribed on one of the rafters as the artificers.[2] It is recorded that up in the dark angles of the roof they sometimes painted, instead of flowers, little figures of Morris with his legs straddling out like the portraits of Henry VIII for the slim young man of the previous year was now not only, in a charming phrase used of him at the time by Burne-Jones, ‘unnaturally and unnecessarily curly’, but growing fat. (1:127)

The ceiling of the library at the Oxford Union as it appears today

© Thomas Corrick, Oxford Union Society Library

Cecil Lang, in his edition of the letters of Swinburne, published in six volumes between 1959 and 1962, provides a transcript of a letter from Swinburne to Edwin Hatch, written on 17 February 1858. It details an amusing incident involving Swan during the campaign to decorate the Union.

“One evening—when the [painting of the] Union was just finished—[Burne-]Jones and I had a great talk. Stanhope and Swan attacked, and we defended, our idea of Heaven, viz. a rose-garden full of stunners. [This was Rossetti’s slang for beautiful women.] Atrocities of an appalling nature were uttered on the other side. We became so fierce that two respectable members of the University—entering to see the pictures—stood mute and looked at us. We spoke just then of kisses in Paradise, and expounded our ideas on the celestial development of that necessity of life; and after listening five minutes to our language, they literally fled from the room! Conceive our mutual ecstasy of delight.” (17-18)

Rossetti’s letters to Ford Madox Brown in June 1859 refer to two occasions on which Swan was in Rossetti’s company—one of them a visit to Brown that found him to be away from home. The most significant reference is in a letter dated 22 June which hints that Brown had perhaps sounded some kind of warning about Swan, or at any rate expressed reservations about him. “As to Swan,” wrote Rossetti:

“I must tell you that he asked me yesterday whether I would take him as a pupil. I gave him no positive answer, but told him I would take him on trial (as a friend) if he would come & paint here next week. What the upshot of it may be I know not. It struck me that if not proving a hopeless case, I might without scoundrelism charge him a pretty fair annual sum & take him on daily, giving him such attention as I could, for certainly he will waste more time & money without than with this plan in his flounderings. But all this is in the womb of time, & I will not forget what you wrote.” (Fredeman, 260)

There is no evidence that the proposed master-pupil relationship between Rossetti and Swan ever came to anything.

Rossetti’s letter is particularly curious, and helps to highlight some other oddities in sources already referred to. If the Swan in question was Henry Swan, it seems peculiar that neither here nor anywhere else was he ever described as a friend of Ruskin’s. Moreover, why would Henry Swan, who had first attended Ruskin’s classes at the Working Men’s College nearly five years earlier amd who had already demonstrated his mettle by copying medieval illuminated manuscripts for Ruskin, choose this moment to ask Rossetti for art lessons? How could Henry Swan’s obituarists have all missed the fact that he had worked with Morris, Rossetti and Burne-Jones, and had made such an important contribution to the decoration of both the Oxford Union and the Oxford University Museum? Admittedly, the reference to Swan’s “flounderings” might tempt us to think that a negative reference is being made to Henry Swan’s eccentric inventiveness, specifically to his experimentation with three-dimensional photography which was then at its peak. But the timing of this request for art lessons is doubly curious for the facts that Henry Swan was by then 34 years of age, and just under three weeks before Rossetti’s letter was written he married Emily Elizabeth Connell (1835-1909) at Hackney Register Office. One might reasonable have expected a man in these circumstances to have sought to improve his lot prior to getting wed, and before patenting a photographic process that involved colouring portraits by hand. He was also busy working as a commercial clerk for a Quaker bookseller in the City.

Fredeman acknowledges an alternative ascription made by Lang who speculated that the mysterious Swan was in fact Francis Henry Swan “who, aged 18, matriculated at Oxford in 1843” (1:17; also qtd Fredeman, 259n). This notion seems to rely entirely on the fact that the candidate was about the right age and had an Oxford connection. Digging into the biography of the remarkably long-lived Francis Henry Swan (1825-1919) reveals no obvious artistic or Pre-Raphaelite sympathies. Though he entered University College, Oxford in 1843, just over a year later he entered Christ’s College, Cambridge. He followed his father into the Anglican clergy and, like him, served at churches in Lincolnshire.

It is thanks to a reference in Georgiana Burne-Jones’s account of her husband’s life that we owe proof of Swan’s identity, or at least the identity of the Swan involved in the Oxford Union work. She refers to the rooms at 17 Red Lion Square, previously occupied by Rossetti, and used by Morris and Burne-Jones from 1856 to 1859—rooms close to the Working Men’s College.

“The Red Lion Square rooms were transferred to Mr Swan, whose acquaintance Morris and Edward had made while painting the Union, and whose outward appearance may be gathered from [Red Lion] Mary’s exclamation when he first called on them, ‘Oh, sir, here’s a gentleman out of Byron come to see you!’ The likeness did not alarm her, however, for she stayed on as housekeeper to him and working at embroidery for Morris until her marriage.” (189)

The Byronic hero sounds little like an Anglican clergyman or a Quaker (even an unusual one), but the clue that unlocks the mystery is the claim about the tenancy of 17 Red Lion Square.

The true identity of this remarkable man is Joseph Swan (1831-1902), who was recorded on the 1861 census as a lodger at 17 Red Lion Square. He describibed himself as a “painter”, a term that arguably fits more comfrtably with a man involved in interior decoration than the grander claim to be an “artist”. He was also—in common with Benjamin Woodward and many of the people favoured to work on Woodward’s buildings—an Irishman.

![]()

1861 census: 17 Red Lion Square

I have discovered frustratingly little about Joseph Swan. He was born in Dublin in 1831. His parents were William Swan (1795-1853) and Thomasine Eleanora, née Reed (1803-1880). His paternal grandfather had owned Baldwinstown Castle, Co. Wexford. A writ issued in 1864 by the Chancery Court in Ireland described Joseph Swan as an artist with a studio and office at 17 Red Lion Square.[3] By the following year he had moved to Paddington, and on 8 June 1865 he married Kate Feldon (1836-1920) at the Church of St Peter-in-the-East, Oxford, now part of St Edmund Hall. At the time of the wedding, Kate was still living with her family just around the corner from the church at 33 High Street where she had grown up. This property was part of Drawda Hall belonging to The Queen’s College, and was shared between college servants, the Feldon family, and the tailoring business run by Kate’s father, Thomas Feldon (1796-1874). It seems reasonable to speculate that Joseph Swan met young Kate Feldon when in Oxford working on the Union. During the “jovial campaign” Morris and Burne-Jones took accommodation at 87 High Street opposite The Queen’s College.

Given the dearth of information on Joseph Swan’s artistic career, it seems probable that he gave up on his active art-work following his marriage. He seems to have fallen out of touch with his famous friends, and lived on his inheritance. He and Kate do not appear to have had any children, and lived at houses in Kensington (Russell Road, 1871; Pembroke Square, 1881), and Hammersmith (Poplar Grove, 1891, 1901) where Joseph Swan died on 16 December 1902. Widowed, Kate returned to Oxford, and died at 35 Iffley Road on 13 March 1920.

A tantalizing if highly improbable possibility remains. The “Mr Swan” involved in the Oxford University Museum work might not be the same man—Joseph Swan—who worked on the Union. There is no definite proof. But the circumstantial evidence is strong, and on close scrutiny Henry Swan does not seem to have been involved in these fascinating Pre-Raphaelite campaigns to beautify two of Oxford University’s most distinctive Ruskinian buildings.

With thanks to Danielle Czerkaszyn, Senior Archive and Library Assistant at the Oxford Museum of Natural History, and Thomas Corrick, Librarian-in-Charge, Oxford Union Society, for responding so helpfully to my enquiries towards the preparation of this post. Additional thanks to John Holmes, Professor of Victorian Literature and Culture at the University of Birmingham, and Prof. Paul Smith, Director of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, for their encouraging and positive responses to this blog post ahead of publication.

Please send feedback to contact@stuarteagles.co.uk

NOTES

[1] Letter from John Ruskin to Henry Swan (1 February 1855). Letters from John Ruskin to Henry and Emily Swan, 1855-1887, 239 unpublished letters, edited by William Allen. Rosenbach Museum & Library, Philadelphia. EL3. R956 MS1. Transcribed by Mark Frost (with thanks).

[2] I.e. Charles Faulkner (1833-92) and Richard St John Tyrwhitt (1827-95).

[3] See The Irish Jurist, vol. 16 (1864) 362; and Irish Chancery Records, vol. 16 (1866) 362.

WORKS CITED

Burne-Jones, Georgiana. Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd, 1906.

Chapman, Alison & Meacock, Joanne. A Rossetti Family Chronology. London: Palgrave, 2007.

Fredeman, William E. (Ed.) The Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. (10 vols.) Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2002-15.

Hargrave, W. “The Faithful Steward of the Ruskin Museum (By One Who Knew Him)”. Pall Mall Gazette (2 April 1890).

Holmes, John. The Pre-Raphaelites and Science. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 2018.

Holmes, John. Temple of Science: The Pre-Raphaelites and Oxford University Museum of Natural History. Oxford: Bodleian Library, 2020.

Lang, Cecil Y. (Ed.) The Swinburne Letters. (6 vols.) New Haven: Yale UP, 1959-62.

Mackail, J. W. The Life of William Morris. (2 vols; new edn) London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1901.

O’Dwyer, Frederick. The Architecture of Deane & Woodward. Cork: Cork UP, 1997.

Oxford University Museum of Natural History. News Release: “Museum of Natural History HOPE for the future wins Lottery Heritage Fund support” (27 March 2018)

Ruskin, John. The Works of John Ruskin. (39 vols.) Ed. E. T. Cook and Alexander Weddburn. London: George Allen, 1903-1912.