In his latest Ruskin Research Blog, Stuart Eagles looks at an argument Ruskin had with an ideal husband about …

THE CRAZE FOR CHEAPNESS

In August 1912 an article appeared in the provincial press which asked, “Was Ruskin Right?” It was part of a column called “From the Husband’s Chair” and the writer was Arthur Stannard (1852-1912).

Sadly, Stannard was only weeks away from death. In life he had gained some celebrity as the ideal husband of a famous woman. Mrs Henrietta Eliza Vaughan Stannard (1856-1911) was famous as the prolific and popular novelist of army life, John Strange Winter. Ruskin admired her books and he became a friend of the Stannard family. I write extensively about the relationship in a forthcoming essay.

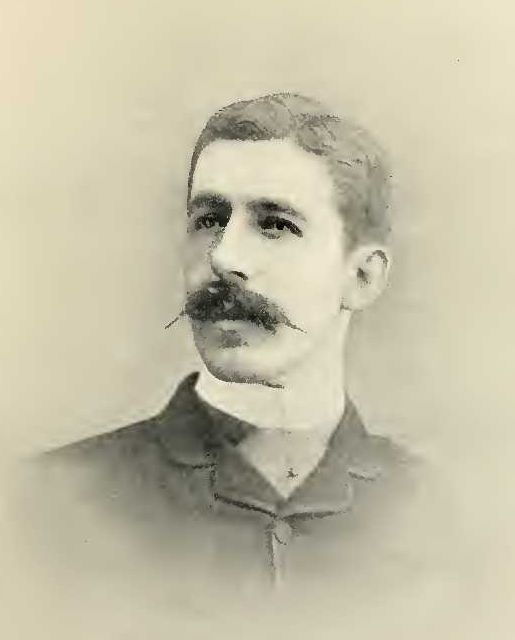

Arthur Stannard

Arthur Stannard

Part of what made Arthur Stannard an ideal husband was that, in a society which expected gentlemen of his class to be the sole earner, and mothers of Mrs Stannard’s class to be household goddesses, he gave up practice as a civil engineer to assist his wife in her literary work. He appears to have been unerringly and uncomplainingly supportive, and combined the roles of agent, adviser, secretary, and proof-reader.

Always interested in practical fashion, Mrs Stannard, who founded the Anti-Crinoline League and supported the campaign for Rational Dress, even formulated some skin and hair products which she marketed under her pseudonym. Arthur served as the managing director of the company. These so-called “Toilet Preparations” were aimed squarely at the English abroad who were battling to protect themselves in sunnier climes: the Stannards themselves lived for many years in Dieppe.

John Strange Winter is largely forgotten now. But she is still remembered for the kindness she showed Oscar Wilde when he lived in France following his release 125 years ago from Reading Gaol.

Mrs Stannard died at the end of 1911, so when Arthur came to ask “Was Ruskin Right?” he wrote not as a husband but as a widower. Nevertheless, Arthur’s article was rooted in past events. It focussed on his late wife, her books, and a rare and illuminating moment of disagreement between himself and Ruskin.

WAS RUSKIN RIGHT?

Ruskin probably only ever met the Stannards when they visited him in early 1888 in Sandgate where he was convalescing, so we can confidently assume that the conversation Arthur recollected took place then.

Arthur explained that he was on the receiving end of “a scathing denunciation” from Ruskin, “for degrading my wife’s art by allowing [her novel] Mignon’s Secret [1886] to be published at one shilling.”

The account of Arthur and Ruskin’s argument serves as a helpful reminder of what Ruskin wrote about “the craze for cheapness” and its social, economic and moral implications. It is a subject that frequently animated him. It also speaks to Ruskin’s ethics and purpose in setting up his friend and disciple, George Allen (1832-1907), as his publisher.

I will let Arthur explain the matter by reproducing below the bulk of the relevant section of his article. I have made only a few minor omissions. I would merely add that the generosity and perspicacity Arthur Stannard demonstrates here appears to be entirely characteristic of him.

“I will not say [Ruskin] was not justified in his general opposition to the craze for cheapness—for not only literature, but everything else, has suffered enough by it since to well warrant our thoughts turning Ruskin-ward to-day […].

“I could not clothe my feelings as picturesquely as Mr Ruskin did his; but, as at that time my wife preferred the shilling form of book, and I entirely agreed with her, of course, I frankly defended our choice as well as I could.

“I maintained that as one shilling left the author a fair margin of profit and carried what he deemed a pure gem of fiction to thousands who certainly would never have read it if restricted by a prohibitive price, we were justified both ethically and commercially in publishing at that price, and, indeed, more to be commended than he was in placing a needlessly high price on his message to the world, particularly if he believed in his gospel.

“I was audacious enough to suggest that it was blameworthy arbitrarily to tax knowledge more than was necessary to secure adequate reward to the producer. I argued that commerce above all things should be righteous, as it was a necessity of life […].

“Therefore in all matters of commerce —and even book publishing was commercial whatever the book contained—justice to all parties should be the ideal, and prices should be so fixed as to ensure adequate reward to the creator’s brainwork and to all concerned in producing and selling […]; no price […] should be condemned as too low, while any artificially raised price might well be condemned if it deprived willing readers of access to wholesome knowledge or pleasure […].

“[Ruskin] said I was outrageously wrong, but sadly owned that even Mr [George] Allen (his devoted publisher) was tainted with my heresies. Later on, Mr Ruskin told me he should ‘write to Allen that he might do as he pleased about cheap editions’.” —Arthur Stannard, “Was Ruskin Right?” in Alderley & Wilmslow Advertiser (23 August 1912).

How far this conversation resolved Ruskin to sanction the publication of Allen’s popular editions of his books is not clear, but there are good reasons to trust Arthur Stannard’s recollections and to believe that the exchange played a part in Ruskin’s evolving attitude to the world of publishing. Ruskin did spend several days with the Allens at their home in Orpington, Kent, at the end of April 1888, shortly after this conversation would have taken place.

“All the same”, Arthur conceded, “Mr Ruskin was nobly right in his scathing contempt for cheapness as an ideal. Like money, it is a righteous factor enough as such; as a single ideal it is fundamentally degrading.’

Arthur concluded his column with words of qualified appreciation that Ruskin’s admirers would do well to consider carefully. His recognition of Ruskin’s limitations are important. Yet, while the two men may have disagreed on certain matters, at a fundamental level Arthur Stannard understood Ruskin’s ideals and was sympathetic to them. He voiced the belief that Ruskin’s influence was on the rise—a vain hope in the context of 1912. But the reasons he gave for wishing that Ruskin’s ideals were widely accepted are timeless.

“If there is to-day […] a tendency to revert to Ruskin’s teaching, I can imagine no deeper cause for thankfulness; for who can doubt that of all our great writers and thinkers he touched most independently and fearlessly the highest and purest ideals for progress? If in his sturdy passion for beauty of thought and aim he sometimes clothed utilitarianism with excessive denunciation—and thereby hindered acceptance of his own great ideals, as violence either of language, action or thought invariably does hinder progress—that does not destroy the essential value of the gospel, much as it may set back the clock. Was not his gospel mainly one of thoroughness in the individual and helpfulness to others? It might well tinge much of the vulgar commercialism of to-day; it would be to our general advantage.”

Ruskin was right.

Please send feedback to contact@stuarteagles.co.uk