In his latest Ruskin Research Blog, Stuart Eagles stays local and discovers another intriguing and unexpected connection between his hometown of Reading and Victorian polymath, John Ruskin …

THE LOVE OF BOOKS &

THE JOY OF READING

Yes, dear reader, my title is a deliberate if limp pun. I mean to refer principally, of course, to the joy of reading (the practice of interpreting written language), but Reading, my hometown, situated in the southern English county of Berkshire, has joyfully and once again unexpectedly presented me with an unlooked-for connection with Ruskin.

The focus of today’s blog is one of Reading’s most interesting residents of the nineteenth century, Mr George Lovejoy. Lovejoy was a bookseller and the founder of a remarkable private circulating library. What makes him particularly fascinating is his relationship with important literary figures, among them Mary Russell Mitford and Charles Dickens. And, yes, John Ruskin, who was himself fond of Mitford and Dickens, and called Lovejoy a “true friend”.

GEORGE LOVEJOY

George Lovejoy (1808-1883) was exactly 11 years’ Ruskin’s senior. He was born on 8 February 1808 in the heart of Reading, just off Minster Street which lies between the Church of St Mary Minster and what today is the Oracle Shopping Centre.

George’s father, Charles Lovejoy, worked at the Abbey Mill on the Holy Brook, a channel of the River Kennet. Local obituaries claim that George attended Reading’s Blue Coat School, and other sources say he was (alternatively or perhaps additionally) educated in the grounds of the former Reading Abbey, founded just over 900 years ago and broken up by Henry VIII. The remaining Abbey Ruins have been attractively preserved. Coincidentally, the former Abbey Gateway, much restored over the centuries, served briefly as a school attended by Jane Austen.

George Lovejoy was apprenticed to Smart and Cowslade, the owners and publishers of the Reading Mercury, one of England’s first provincial newspapers. He quickly established himself as a skilled compositor and printer. In his early 20s he became the manager of the stationery and bookselling department.

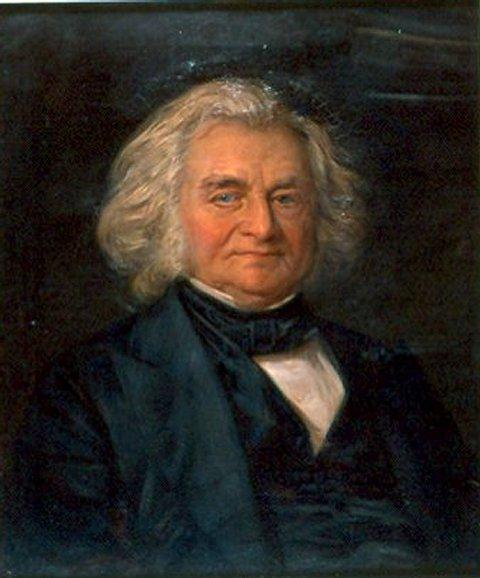

A local artist, Edmund Havell (1785-1864), who followed his father as drawing master at Reading Grammar School, owned a stationer and circulating library at 31 London Street. He was declared bankrupt in 1832. With a loan from his friend, William Silver Darter, Lovejoy purchased Havell’s business and also set himself up as a bookseller. Havell’s younger brother, Charles, would paint a portrait of Lovejoy in 1850.

Charles Havell’s portrait of George Lovejoy (1850).

© Reading Museum, Reading Borough Council.

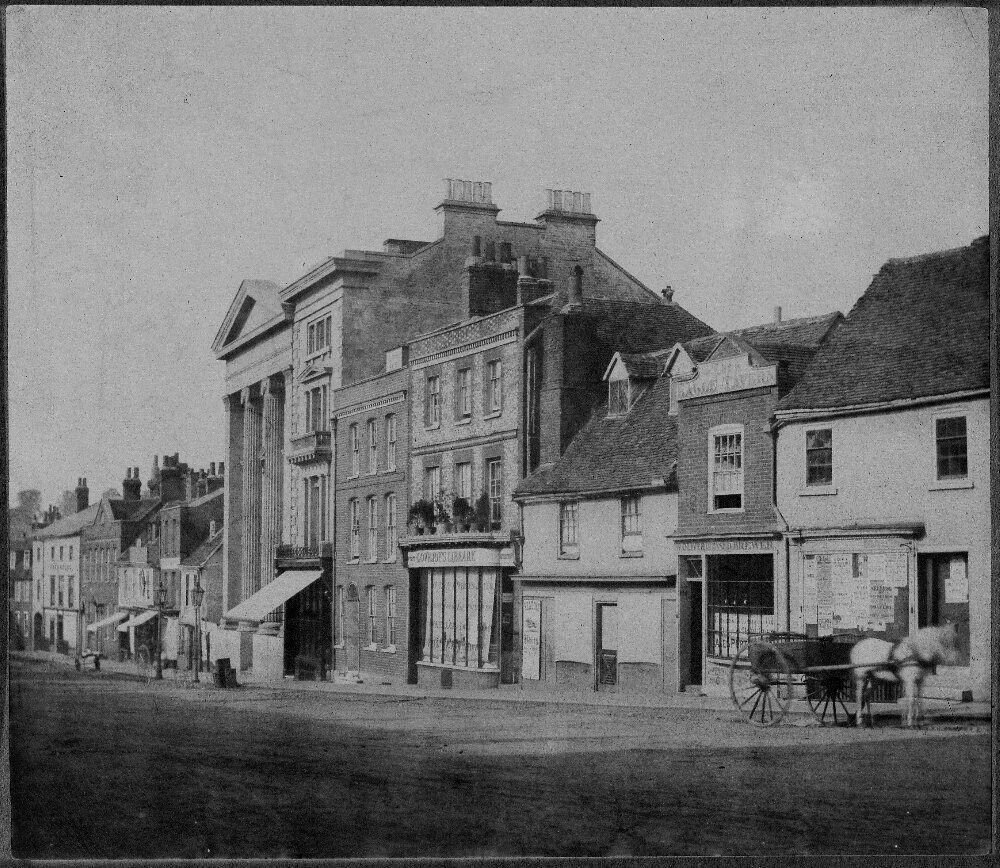

Lovejoy’s library and bookshop at no. 31 was located on the east side of London Street. It was demolished in 1840 to make way for “the New Public Rooms”. We will consider this institution in more detail below, because both Mitford and Dickens played a part in its story, but it is sufficient to state at this point that its foundation was actively supported by Lovejoy. The building survives today, and though much changed inside, its imposing Greek Ionic frontage with its two engaged, fluted and decorated columns remains intact.

In 1840 Lovejoy moved his business a few doors south to no. 39, an eighteenth-century property which incorporates an older building, and has an alleyway on its southern edge leading to Sims Court. The library continued to expand, and Lovejoy added the selling of prints, ticket5s for local events, insurance and postal services to his enterprise. He extended the property at no. 39 in 1869, and in 1878 expanded into no. 37 next door, where Lovejoy’s sister, Mary, one of his shop assistants, had lived since 1856. Today this pair of buildings is home to the Reading International Solidarity Centre (RISC) which boasts a fairtrade retail shop and the Global Café.

From the mid-nineteenth century to 2022: today, Lovejoy’s bookshop and library on London Street, is home to the Reading International Solidarity Centre.

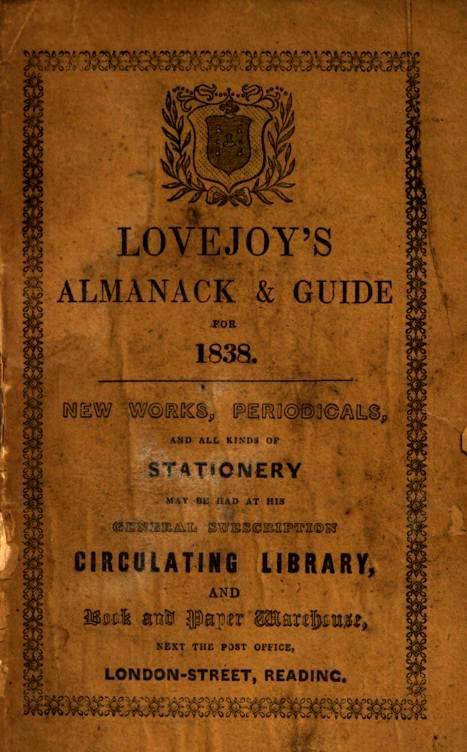

Lovejoy compiled an ever-growing library catalogue, and for many years he also published an annual almanack. He established a formidable reputation for his Southern Counties’ Library, reputedly the largest private circulating library in England outside London. By 1853 he had amassed a collection of 40,000 volumes; at his death 30 years later he had nearly twice that number, and he boasted 268 subscribers. Among Ruskin’s books on loan from Lovejoy were Modern Painters, The Seven Lamps of Architecture, and The Stones of Venice, and probably many other titles: a newspaper report written after Lovejoy’s death referred to “a valuable collection of the scarce and beautifully illustrated works of Mr Ruskin” (Reading Observer, 7 November 1885).

Lovejoy compiled an ever-growing library catalogue, and for many years he also published an annual almanack. He established a formidable reputation for his Southern Counties’ Library, reputedly the largest private circulating library in England outside London. By 1853 he had amassed a collection of 40,000 volumes; at his death 30 years later he had nearly twice that number, and he boasted 268 subscribers. Among Ruskin’s books on loan from Lovejoy were Modern Painters, The Seven Lamps of Architecture, and The Stones of Venice, and probably many other titles: a newspaper report written after Lovejoy’s death referred to “a valuable collection of the scarce and beautifully illustrated works of Mr Ruskin” (Reading Observer, 7 November 1885).

Over the years Lovejoy won support for his venture from across the south of England. The statesman Lord Brougham (1778-1868) reportedly said that in his day it was the best provincial library in the kingdom. Among frequent visitors were Charles Kingsley (1819-1875), the vicar at Eversley, Hampshire, under ten miles from Reading, and the Irish novelist, Anna Maria Hall (1800-1881).

Lovejoy was strongly philanthropic in outlook. Although his own library was set up for the use of private subscribers, he welcomed visits to his premises from less well-off students, and energetically supported the establishment of a free library in Reading. Although the borough did not open a public library until 1883, the year in which Lovejoy died, the local biscuit manufacturer William Isaac Palmer opened an affordable library service at West Street Hall which had 3,500 volumes and up to 400 regular readers.

Lovejoy was a nonconformist who attended the Baptist Church in King’s Road. He was also a Temperance campaigner, a member of the Peace Society, and an advocate for the abolition of capital punishment. He was, above all, dedicated to the cause of education, and the advancement and welfare of the young. Although he once served the borough as Auditor, he was a frequent and vocal critic of the Town Council. He remained active until the very end, attending a gathering of the Reading branch of the Help-Myself Society just a week and a half before he died.

MARY RUSSELL MITFORD

Among Lovejoy’s better-known early supporters and library subscribers was the poet, dramatist and author, Mary Russell Mitford (1787-1855). She often used Lovejoy’s Library and once wrote of him as her “excellent friend, Mr Lovejoy, our great Reading bookseller”. In July 1843 she wrote:

“I cannot wait in the matter of books, I have been too much spoiled. At this moment I have eight sets of books belonging to Mr Lovejoy. I have every periodical within a week, and generally cut open every interesting publication—getting them literally the day before publication.”

Miss Mitford is most fondly remembered as the author of Our Village, the charming sketches of rural life in the 1820s and 1830s centred around her home in Three Mile Cross, five miles south of Reading.

Miss Mitford’s cottage at Three Mile Cross as it appears today, and a close-up of the commemorative plaque, © Stuart Eagles. Ruskin was among her visitors there in the late 1840s.

Miss Mitford also wrote about life in Reading, re-naming the town Belford Regis in two volumes of sketches written in the 1830s. She spent some of her childhood living just around the corner from what became Lovejoy’s bookshop and library—on the north side of London Road, at no. 39, the home today of Kendrick View Dental Practice.

Miss Mitford’s childhood home at 39, London Road, Reading,

as it looks today, © Stuart Eagles.

Mary Russell Mitford is particularly interesting to Ruskin scholars because of the close friendship that developed between them. In the words of Ruskin’s editors, Cook and Wedderburn, “She was wisely sympathetic to him, and Ruskin on his side did much by kindness and thoughtful generosity to cheer her closing years.” (Ruskin, Works, 12.xxxix) She greatly admired Ruskin’s Modern Painters, even if—in common with her friend Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-1861), to whom she recommended the book—she did not always agree with his opinions. For his part, Ruskin was charmed by the authenticity of Mitford’s portrayal of country life. He visited her several times at Three Mile Cross, for the first time in January 1847.

Miss Mitford considered Ruskin “the most charming person I have ever known […] just what if one had a son one should have dreamt of his turning out, in mind, manner, conversation, everything.” (See Ruskin, Works, 36..xxix-xxx, specifically xxix) Ruskin and Miss Mitford wrote to each other often, and even when Ruskin was abroad he made an effort to send her interesting reading matter.

Books were, of course, the focus of Miss Mitford’s relationship with George Lovejoy. She was his customer as well as his friend. A letter she wrote in December 1847 to her friend, Charles Boner (1815-1870)—the travel writer, poet and translator—reveals more about the relationship and helps to flesh out the nature and extent of Lovejoy’s mission.

“I have been thinking of you and talking of you lately, having been engaged (as indeed I still am) in making out a list of secular books for lending libraries for the poor. The young wife of a clergyman, a girl of sense, wrote to me to say she could find no such list except of tracts and sermons! so dear Mr Lovejoy and I have fallen to work, and when we have completed our labour we shall send you a copy. We mean to set down the very best books (which are luckily the cheapest), upon the plan of Napoleon, who, you remember, in throwing open the theatres of Paris after a victory or a marriage, always chose a play of Corneille, or of Molière, and always found his choice justified by the gratification and intelligence of the audience.” (Qtd in Elizabeth Lee (ed.), Mary Russell Mitford: Correspondence with Charles Boner and John Ruskin (1914) p. 83.)

CHARLES DICKENS

Lovejoy’s connections were not restricted to local authors. In 1841, he approached Charles Dickens and asked him to stand as the Liberal candidate for Reading in the parliamentary election. Dickens was a friend of Thomas Noon Talfourd (1795-1854), the lawyer, politician and author who was elected Radical MP for Reading in 1835 and again in 1837. Talfourd decided not to stand in the 1841 General Election. However, he was re-elected when he stood again in 1847, but he resigned his seat two years’ later when he was appointed a judge to the Court of Common Pleas.

Talfourd delivered a powerful speech on “literary property” in the House of Commons on 18 May 1837, and his efforts were key to the introduction of copyright law in 1842. Dickens, who fought hard to assert his legal, financial and moral rights over his writings, particularly appreciated Talfourd’s expert support and advocacy, and in gratitude he dedicated The Pickwick Papers to him.

Dickens’s reply to Lovejoy’s request that he stand as Reading’s Liberal candidate in the General Election and thereby become Talfourd’s political successor is worth quoting at length. It was written from his home at 1 Devonshire Terrace on 31 May 1841.

“I am much obliged and flattered by the receipt of your letter, which I should have answered immediately on its arrival but for my absence from home at the moment.

“My principles and inclinations would lead me to aspire to the distinction you invite me to seek, if there were any reasonable chance of success, and I hope I should do no discredit to such an honour if I won and wore it. But I am bound to add, and I have no hesitation in saying plainly, that I cannot afford the expense of a contested election. If I could, I would act on your suggestion instantly. I am not the less indebted to you and the friends to whom the thought occurred, for your good opinion and approval. I beg you to understand that I am restrained solely (and much against my will) by the consideration I have mentioned, and thank both you and them most warmly.”

Lovejoy wrote back on 9 June in an attempt to persuade Dickens to change his mind. He evidently set forth some figures. But Dickens replied that the candidature remained beyond his means, because “the mere sitting in the House [of Commons] and attending to my duties, if I were a member, would oblige me to make many pecuniary sacrifices, consequent upon the very nature of my pursuits”. Lovejoy had also suggested that Dickens might apply for Government support, a possibility that Dickens said had already occurred to him, but which he rejected because it would compromise his “honourable independence without which I could neither preserve my own respect nor that of my constituents”. (The passages from Dickens’s letters to Lovejoy are quoted from The Letters of Charles Dickens, vol. 1 (1833-56) (London: Chapman & Hall, 1880) pp. 44-45.)

It is worth pausing to recall how much Ruskin admired Dickens’s novels. In a famous footnote to his political essays, Unto this Last (1862), Ruskin wrote of his appreciation of Dickens’s political “truth” in the same breath as he regretted its presentation in “a circle of stage fire”. (The paragraph is a long one, so I have split it in two to make it easier to read on screen.)

“The essential value and truth of Dickens’s writings have been unwisely lost sight of by many thoughtful persons, merely because he presents his truth with some colour of caricature. Unwisely, because Dickens’s caricature, though often gross, is never mistaken. Allowing for his manner of telling them, the things he tells us are always true. I wish that he could think it right to limit his brilliant exaggeration to works written only for public amusement; and when he takes up a subject of high national importance, such as that which he handled in Hard Times, that he would use severer and more accurate analysis. The usefulness of that work (to my mind, in several respects the greatest he has written) is with many persons seriously diminished because Mr Bounderby is a dramatic monster, instead of a characteristic example of a worldly master; and Stephen Blackpool a dramatic perfection, instead of a characteristic example of an honest workman. But let us not lose the use of Dickens’s wit and insight, because he chooses to speak in a circle of stage fire.

“He is entirely right in his main drift and purpose in every book he has written; and all of them, but especially Hard Times, should be studied with close and earnest care by persons interested in social questions. They will find much that is partial, and, because partial, apparently unjust; but if they examine all the evidence on the other side, which Dickens seems to overlook, it will appear, after all their trouble, that his view was the finally right one, grossly and sharply told.” (Ruskin, Works 17.31n)

In January 1888 Ruskin wrote to the Daily Telegraph to say that while it was true that he had commented that Pickwick had not amused him when he was ill, nevertheless

“it always does, to this hour, when I am well; though I have known it by heart, pretty nearly all, since it came out: and I love Dickens with every bit of my heart, and sympathise in everything he thought or tried to do, except in his effort to make more money by readings, which killed him.” (Ruskin, Works, 34.613)

At this point we must re-introduce the impressive “New Public Rooms” part of which was built on the site of Lovejoy’s original library and bookshop at 31 London Street. Commonly called New Hall, it provided a permanent home for Reading’s Literary, Scientific and Mechanics’ Institute which occupied its front rooms. The large great hall at the rear of the building was used for a wide variety of public events, including lectures, concerts, theatrical evenings and occasionally dinners.

A sketch of New Hall, London Street, Reading,

on its opening in 1843.

The cornerstone of the building was laid late in 1842 by Mary Russell Mitford. She was also present at the public dinner which formally celebrated its opening on Tuesday, 24 October 1843. Dickens had been invited to attend, but sent his apologies. His letter, included in the report of the dinner given in the Reading Mercury (28 October 1843) reads as follows:

“My Dear Sir, —Pray do me the favour to assure the committee of your Literary and Scientific Institution that I am much gratified by their kind remembrance, and that it is not a little matter which should prevent me from accepting their invitation for the 24th. I regret to add, however, that urgent engagements render it out of my power to attend. I am not the less obliged to the committee and yourself; and with my cordial wish for the success of your New Building, and with much pleasure in knowing that my friend Mr Serjeant Talfourd will be present at its christening, as the representative of literature, and the champion of its rights,

“I am, dear Sir, faithfully yours, CHARLES DICKENS.”

Talfourd was indeed present at the dinner. Among the “engagements” which prevented Dickens’s attendance was the writing of his latest literary creation: he had just begun six weeks of intensive work which would give the world A Christmas Carol, “no little matter” indeed.

Appropriately, 11 years later, on 19 December 1854, when Dickens was serving as the President of the Mechanics’ Institution, he gave a dramatic reading from A Christmas Carol to a large crowd assembled at the New Hall. Also present were Dickens’s wife Catherine, his sister-in-law Georgina Hogarth, the artist Clarkson Stanfield, Mark Lemon (the editor of Punch), W. H. Wills (co-editor of Dickens’s journal, Household Words), and John Forster (then the editor of the Examiner, and later Dickens’s biographer). According to a report printed in the Reading Mercury on 23 December 1854, Dickens was “vociferously cheered”.

This was neither the first nor the last occasion on which Dickens would give a dramatic performance in Reading.

Mark Lemon and John Forster were among the friends to accompany Dickens in 1854 who joined him in the Amateur Company of the Guild of Literature and Art. On 23 December 1851, the company performed at Reading Town Hall, at the invitation of the Mayor, W. S. Darter (the friend who had made Lovejoy his crucial loan in 1832). The show was Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton’s comedy, Not So Bad As We Seem, or, Many Sides to a Character, specially written for the tour, and set in the political landscape of the eighteenth century. Joining Dickens, Lemon and Forster in the cast were Wilkie Collins, Douglas Jerrold, John Tenniel, Charles Knight (who played a bookseller), Augustus Egg, Dudley Costello, F. W. Topham, Peter Cunningham, Robert Bell, and R. H. Horne. The most comprehensive report appeared in the Berkshire Chronicle (27 December 1851) which included the delicious observation that “coldness is an unfavourable characteristic of Reading audiences in general”, but overcame that tendency to commend Dickens as “admirable throughout. His manner is extremely graceful and polished: his voice, though rather weak, possesses a clear intonation, and his style is very calm and emphatic […] his versatility of expression is most remarkable.” The performance was followed by the one-act farce, Mr Nightingale’s Diary, written by Dickens and Lemon.

Dickens returned to Reading on 8 November 1858, for his second turn at the New Hall. On this occasion a crowded audience watched his dramatic reading of the “Little Dombey” scene from Dombey & Son, followed by “the trial scene” from The Pickwick Papers: “every one departed with the highest feelings of pleasure at the great treat which had been afforded them”. (Reading Mercury, 13 November 1858.)

New Hall was destined to be put to various uses over the years. From 1866 to the 1940s it served as a Primitive Methodist Chapel. For most of the 1950s it was the Everyman Theatre. It was even used for a time by the Reading Standard. It is now a Dickens-themed hotel and bar called Great Expectations.

According to his obituary in the Reading Observer, Lovejoy treasured an ink-stand belonging to Dickens with which he was reportedly presented by one of Dickens’s sisters. The same source claims that Dickens last visited Lovejoy’s shop on his way to Farley Court near Swallowfield, an occasion on which he was accompanied by Anthony Trollope and Edmund Yates.

JOHN RUSKIN

And, at last, we come to George Lovejoy and Ruskin. The exact nature of Ruskin’s connection with Lovejoy is not entirely clear. However, Lovejoy’s obituary in the Reading Observer noted that he “carried on correspondence with many leading writers, and frequently showed his friends the letters be had received from John Ruskin and others”. It continued, “As recently as August last he got an interesting letter from Mr Ruskin, of which we have been favoured with a copy” and, as luck would have it, the newspaper quoted it in full. Hitherto it does not appear to have been re-produced by Ruskin scholars.

(In giving it here, I have only intervened to split the text into shorter paragraphs for ease of reading on screen.)

The opening remarks refer to the fact that, partly on the advice of his doctor, Ruskin left England on 10 August 1882. He embarked on a tour of France, Switzerland and Italy with his valet, Peter Baxter, and his secretary, W. G. Collingwood, another man with Reading connections which we shall explore another day. They did not return to England until 2 December.

“Herne Hill, [Tuesday] 8th August, 1882.

“Dear Mr. Lovejoy, —

“It is quite one of my happiest duties, before leaving England this year, to thank you for your sympathy and kindly wise expression of it, in the way you lend my books.

“I heard of it, some time since, from [name blanked out] and was deeply touched by it, and just now being reminded that I have such a true friend is of more than help to me, in a time of great languor and falling courage.

“Yet, curiously, in spite of this depression I have this very morning written a sentence about my books, which some people will think very arrogant, but which, nevertheless, I felt it a duty to write, saying that I have not been warped in my search for truth by any vanity of originality, but have written only what I knew, for the good of others, and that, as I grow old, I am thankful to find the work gather itself into a system in which I desire to make no change or retraction.”

[Ruskin wrote in the second volume of Modern Painters (1846): “That virtue of originality that men so strain after is not newness, as they vainly think (there is nothing new), it is only genuineness”. (Ruskin, Works, 4.253)]

“Yon are the first person to whom I venture to say this, as you are indeed the only one, among the men occupied in the book trade, whether in this or other countries, whom I have heard of as rightly understanding his own influence and generously using it.

“You will I think be glad to hear that in spite of illness and sadness, I am still able to carry on the books announced in my last prospectus if less rapidly, I believe also less petulantly than in former days.—

“Believe me ever,

“faithfully and gratefully yours,

“JOHN RUSKIN.”

The bookshop and library were continued after Lovejoy’s death by his assistant of 21 years’, Eliza Langley (-1897). But some of Lovejoy’s collection was auctioned off, including two copies of the first edition of the first two volumes of Modern Painters (sold for £26 10s and £27 respectively). The most significant volume of Ruskin sold from Lovejoy’s collection, though, was a presentation copy of The Stone of Venice, signed by the author to Mary Russell Mitford. It sold for £25. (See Reading Mercury (15 December 1883).)

The final words are taken from Lovejoy’s obituary in the Reading Observer.

“His library has been a spot to which men of all shades of political and religious opinion gravitated. There those opinions found expression, and in Mr Lovejoy met with a sympathetic hearer or an honest outspoken opponent.”

Unless otherwise stated, quoted text comes from Lovejoy’s obituary in the Reading Observer (21 July 1883).

See also my blog #13, “Ruskinian Redlands” (published 23 May 2021).

Please send feedback to contact@stuarteagles.co.uk