In his latest Ruskin Research Blog, Stuart Eagles looks back at the moment in November 1883 when William Morris declared for socialism in front of an audience at University College, Oxford. John Ruskin, the Slade Professor of Fine Art, responded warmly. Looking at the recollections of three undergraduates who were involved, Eagles follows threads that weave together Arnold Toynbee, The Prisoner of Zenda, and The Wind in the Willows, and sheds light on

RUSKIN & MORRIS AT OXFORD (Part I):

DECLARING FOR SOCIALISM

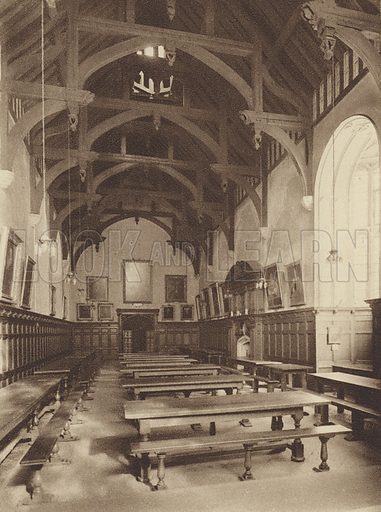

University College, The Hall. Illustration for Oxford, the Colleges and University Buidings with an introduction by Christopher Hussey (Country Life and George Newnes, 1932). Gravure printed, not suitable for large repro.

Morris gave his lecture, originally entitled “Art and Democracy”, at the invitation of a Radical Liberal association of undergraduates called the Russell Club. According to the Cambridge Review, Morris delivered “a singularly forcible and eloquent denunciation of the evils of competition” (21 November 1883) (p. 98). He was clear, open and generous in acknowledging his profound intellectual debt to Ruskin, in particular to Ruskin’s chapter, “The Nature of Gothic” from the second volume of The Stones of Venice (1851-53), which Morris would go on to publish in a new and beautiful edition from the Kelmscott Press. The Oxford Magazine said the lecture was “listened to with great attention and frequently applauded” (21 November 1883) (p. 386).

But Ruskin did not in fact chair the meeting after all. This was comprehensively demonstrated 15 years ago by the scholar Tony Pinkney in his exemplary study, William Morris in Oxford (2007). Anyone interested in this matter should read the third chapter, “The Democratic Federation in Oxford, 1883-84”, a thorough and meticulous account of the lecture and the circumstances surrounding it. Pinkney shows that Ruskin was there in the hall, that he spoke, and also that he gave a further public response a few days later, in his lecture, “The Hill-Side”.

My own account of all this forms the basis of an essay I have written on “Morris and John Ruskin” for the forthcoming Cambridge Companion to William Morris, edited by Marcus Waithe. I shall not present an analysis here either of what Morris or Ruskin said. I want instead to focus on the occasion itself as it was recollected by three of the undergraduates involved in organising it. The event represents an important moment because, in the judgement of several contemporaries, Ruskin passed a kind of Benediction on Morris. In a report commended by Morris himself, the Pall Mall Gazette records that Ruskin called Morris “the great conceiver and doer, the man at once a poet, an artist, and a workman, and his old and dear friend” (Ruskin: 33.390n).

This is the first time that the testimonies of these three undergraduates have been considered together, and in combination with their other reminiscences of Ruskin. The evidence is, anyway, largely unfamiliar in Ruskin scholarship and presenting in this way aims to shine a brighter light on an important moment in Morris’s life at a crucially significant point in his relationship with Ruskin, and at a period of political controversy in Britain when the new socialism seemed to offer a new road on which the world should travel.

In the next blog, the second part of this account, I will look at some of the press reactions to Morris’s lecture, and at a particularly interesting contemporary response to the lecture.

The three student who concern us here were all were all friends who were well-disposed to both Ruskin and Morris: M.E. Sadler, A. H. Hawkins, and J.A. Spender.

Morris’s lecture was “well attended” according to the Oxford Magazine (21 November 1883) (p. 393). Among what the Oxford Journal characterised as “a crowded audience” were many Oxford dons as well as undergraduates (17 November 1883) (p. 5). But it is difficult to know the identities of precisely who was there. The Pall Mall Gazette reported that “heads of colleges, undergraduates, professors, and lecturers” were among those who “jostle[d] one another for places” (15 November 1883) (p. 4).

My survey of a broad range of sources reveals that in addition to Ruskin, Sadler, Hawkins and Spender, Morris’s lecture was attended by at least three College heads: James Frank Bright (of University College), the Hon. George Charles Brodrick (of Merton), and Canon Edward Stuart Talbot (of Keble), the last of whom gave the vote of thanks which John Ruskin seconded. Also present were Vernon Harcourt, Walter Pater, and Ruskin’s colleague at Corpus, Prof. James Legge, the sinologist and linguist who was a close friend of Max Müller. But these are but a few of the many who heard Morris and Ruskin speak on that vitally significant day in 1883.

MICHAEL SADLER

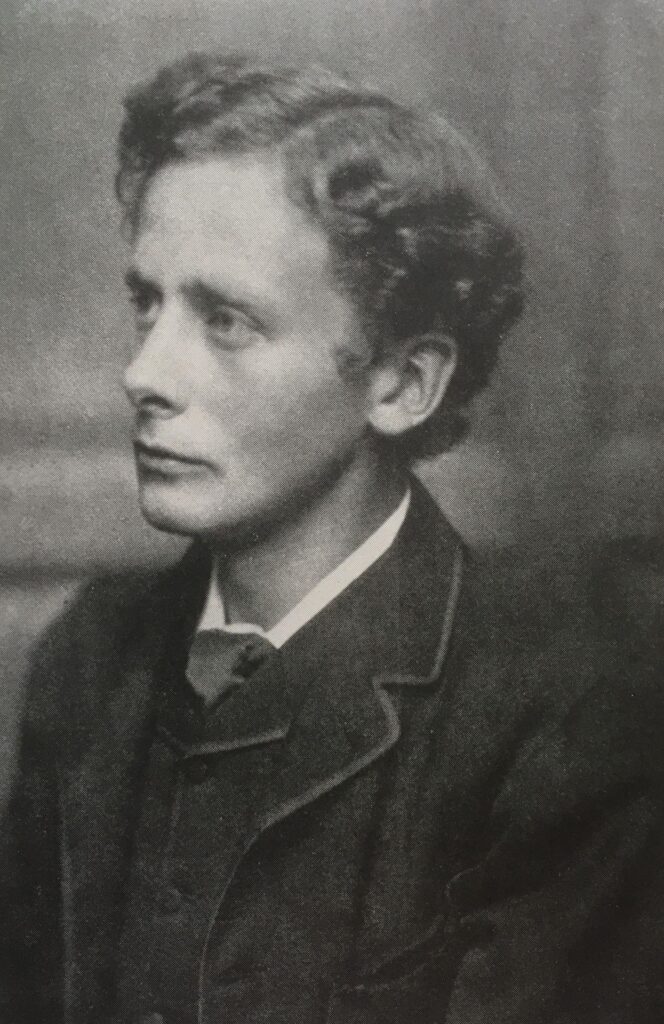

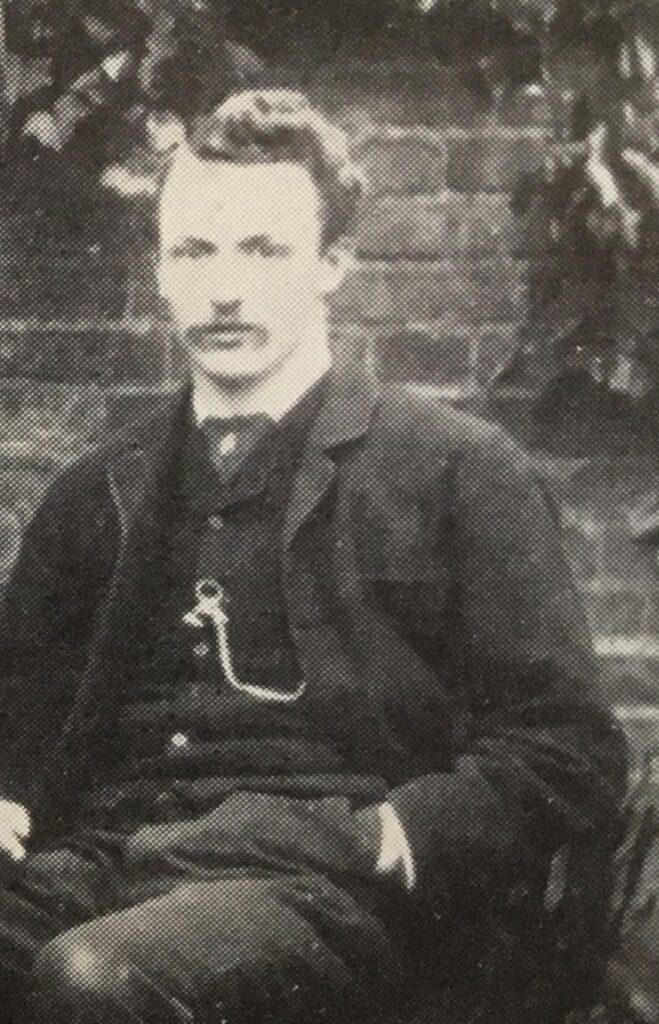

Michael Sadler (1884)

Michael Sadler (1884)

Michael Ernest Sadler (1861-1943) is best remembered today as a Ruskinian educationalist who played a crucial role in the development of the University Extension Movement which provided lecture-courses in the community for people who had not had the opportunity of higher education. In a distinguished career, he served as Vice-Chancellor of the University of Leeds from 1911 to 1923, and from 1923 to 1934 he was Master of University College, the institution that had hosted Morris’s lecture in 1883.

Recalling his student days, Sadler wrote:

“The influence of the aesthetes was at its height. Oscar Wilde left the university two or three years before [in fact, in 1878]. We were all for faded greens and yellows and Burne-Jones photographs. A friend of mine tried to have his lunch on the bare floor, the only decoration a vase with one jonquil in it. We wore our hair very long, and some of the cult affected to take their only exercise on the top of the trams, then a novelty in Oxford.” (Sadleir: 32)

Sadler’s son describes what his father was like about a year before the Morris lecture. He was

“already forming a circle of acceptable friends, an active aspirant at Union debates; a member of the Palmerston and the Browning Societies; a passionate admirer of Ruskin, Clough and Arnold Toynbee; a church-goer, flamboyantly aware of the consolation of religion. He was striving, in short, to combine high thinking with plain living, in a manner to be expected of a young man of great talent, intense seriousness and restricted means.” (Sadleir: 30)

His tendency for “political and economic radicalism” was strengthened “by hearing a paper on the Factory Movement read by Arnold Toynbee”, the socially conscious and politically engaged Balliol historian who as an undergraduate had served as foreman of Ruskin’s road-diggers at North Hinksey (Sadler: 30). It was strengthened, too, by his “Ruskin-worship”—”the awestruck admiration of young enthusiasm for established fame” that made for an ardent discipleship (Sadleir: 32). Sadler attended Ruskin’s lectures, and recalled how difficult it was to get tickets:

“Crowds of people came up from the country and thronged the South Park Road and the steep little lecture theatre at the Museum. I can still see, as clearly as at the time, Ruskin entering the lecture room, escorted by his old friend, Sir Henry Acland. […] Nominally these lectures of Ruskin’s were upon Art. Really they dealt with the economic and spiritual problems of English national life. He believed, and he made us believe, that every lasting influence in educational systems requires an economic structure of society in harmony with its ethical ideal.” (Sadleir: 32-33)

Sir Michael Sadler’s most detailed account of Morris’s lecture was published in his preface to Edith Hope Scott’s history of Ruskin’s Guild of St George (1931). It was written nearly 50 years after the events it describes—indeed, Sadler wrongly gives the year as 1881. Not unreasonably, his recollection was hazy on some points, but in other respects it is a remarkably vivid account. The fact that Sadler was by then Master of University College makes his testimony all the more poignant.

Salder characterises Morris’s lecture as one that principally addressed the “destruction of the secluded beauty of Oxford”, a powerful theme in Morris’s talk and Ruskin’s response to it later in the week (Scott: x). “University College Hall”, Sadler points out, “was then neo-Gothic. Dark-stained serrated panelling lined the walls. A vaulted plaster ceiling recalled the pictures of Gothic romance” (Scott: x).

Sadler misremembers who chaired the meeting. “In the chair, behind an elegant scissor-legged Chippendale table”, he writes, “sat one of my predecessors—Dr Frank Bright—genial in expression, with a furrowed face, eyes like mountain burns, jellying with good humour, and with an iron-grey patriarchal beard” (Scott: x). The historian (James) Frank Bright (1832-1920) was certainly present, and as Master of University College, he hosted the meeting, or at any rate gave permission for the Russell Club to hold its meeting there, but he did not chair the meeting any more than Ruskin did. As we shall see, that honour belonged to someone else.

“William Morris”, Sadler continued,

“stood on [Bright’s] left in a blue reefer suit like a sea pilot: a blue flannel shirt and collar and a red tie, his maritime ruddy beard bristling with energy. So a Viking might have stood. He moved the resolution temperately. But his spirit soared into vehement denunciation of the commercialism of modern Oxford. Dr Bright looked more and more uncomfortable. Leave had been given by the Fellows of the College for the use of the Hall for an orderly business-like meeting against tram-lines in High Street. And here was an honoured guest, connected with the College by close friendship with one of its Fellows beginning to breathe fire against the whole capitalist regime. We were thrilled and a little uncomfortable.” (Scott: x-xi)

Although Sadler was incorrect to say that the purpose of the meeting was to oppose tram-lines and the widening of Magdalen Bridge, he was right to allude to Morris’s “close friendship” with one of the college dons. He was thinking of the mathematician, Charles Faulkner (1833-1892), a partner in The Firm, that pioneering enterprise in Arts & Crafts manufacture. Morris corresponded with Faulkner ahead of the meeting, warning him that he would be every bit as radical as H. M. Hyndman, the founder of the Marxist society, the Democratic Federation—later the Social Democratic Federation—of which Morris had recently become a member.

Sadler then turned to Ruskin.

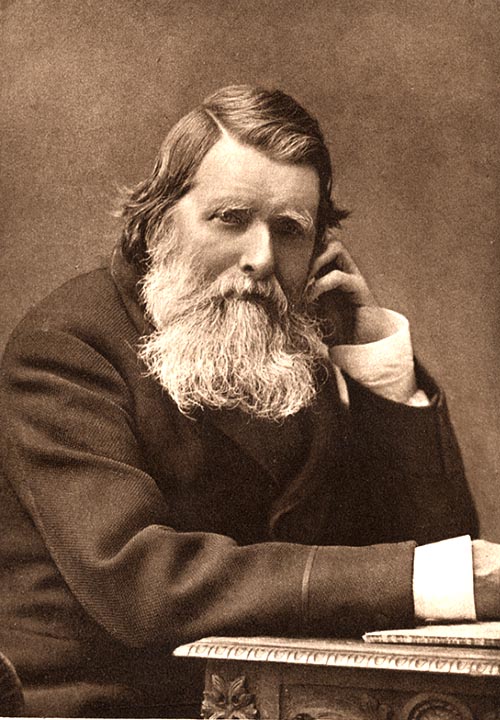

“A step below the dais in a low bow-backed chair sat huddled an old gentleman, nameless to me and never before seen. But there was something in him which radiated power. To his quiet venerable shape one’s eye kept returning in spite of all the hot words of William Morris. Straight iron-grey hair, large pathetic eyes, now pensive, now flashing, light grey tweed trousers, a double-breasted waistcoat of the same grey cloth, a tight black frock-coat, and beneath his collar a vast tie of a vivid shameless blue, which made us—who then were wearing russet silk from Liberty—shiver at such a sight of Philistinism. And, at last, he rose, and his voice was magic. This was the man who broke his heart for England.” (Scott: xi)

Eventually he broke his head, too: he sacrificed his sanity in what he perceived to be his constantly frustrated mission to open people’s eyes and make them see.

John Ruskin

John Ruskin

Sadler had in fact seen Ruskin before this time. Tony Pinkney points out that in a letter written a few days before the meeting, Sadler had described meeting Morris for the first time, and it is clear that he had already seen and heard Ruskin (see Pinkney: 69). Writing from Museum Cottage to his mother on 10 November 1883, Sadler confided:

“At all costs [his sister] Eva sh[oul]d hear Ruskin speak. To see the man is almost an exaltation; to hear him is to be inspired. Not that to feel this one need think his political economy sense or accept even in small measure his social Holloway’s pills. But, all said & done, he has a most marvellous character & insinuating touch of influence—a quiet refinement & gaiety of mind—& an occasional power, which he cannot command at will, of unique influence.

“Last Afternoon I heard him lecture on PUNCH. His analysis of the Whigism of ‘Mr Punch’, of his consistent regard & love for property, his appreciation of the effect of self-control, & repugnance to the poor & the victims of mechanised labour was masterly. But the sentence in which he told of the greatness of the past of England, & asked with profound scorn whether all that can now be said of a country where S[t] George fought & S[t] Augustine preached, which ‘stands, the champion of all succour folded in the mantle of its seas’, is that ‘John Bull is guarding his pudding’—this one sentence quite made my hair stand on end. He drivels at any pretext but he is never commonplace.” (Sadleir: 45)

Sadler appears to be referring to Ruskin’s lecture ‘The Fireside” about John Leech and John Tenniel, delivered on 7 and 10 November 1883, and published in The Art of England (see Ruskin, 33:350-370).

Sadler would not be blind to Ruskin’s deteriorating health and capacity, however. In a sad letter written on 29 November 1884, he recorded:

“Everyone is extremely anxious about Ruskin, who was so excited by the delivery of his addresses that many believed him once again to have lost his head, and all joined in hoping that he would give up his work. I went a week ago and was shocked at the change in him: he was worn and savage, his old playfulness had changed into wild sarcasm—extravagances that before were merely the play of wayward humour had become the pathetically serious wanderings of a maniac. … The reports in the P.M.G. have been practically made by E. T. Cook, who has cleverly concealed much of the inconsequence of the thoughts in the lectures.” (Sadleir: 63)

Describing Morris, with whom he “had the privilege of smoking a pipe on Friday night” [9 November 1883], Sadler called him:

“A little man with short legs & a small meerschaum, a tangled grey beard, high forehead, rough hair, & blue flannel shirt with a tie. A keen talker but slangy. Himself & his friends always ‘chaps’—salmon fishing in an Iceland glacier stream ‘tremendously jolly’, Teuton excellence lying in their love of the ’rough & tumble hullaballoo of a battle’, Romans slack because ‘they didn’t like fighting for its own sake don’t you know’. I could hardly credit his having written the EARTHLY PARADISE. He is full of socialism & has become a political lecturer.” (Sadleir: 45)

ANTHONY HOPE

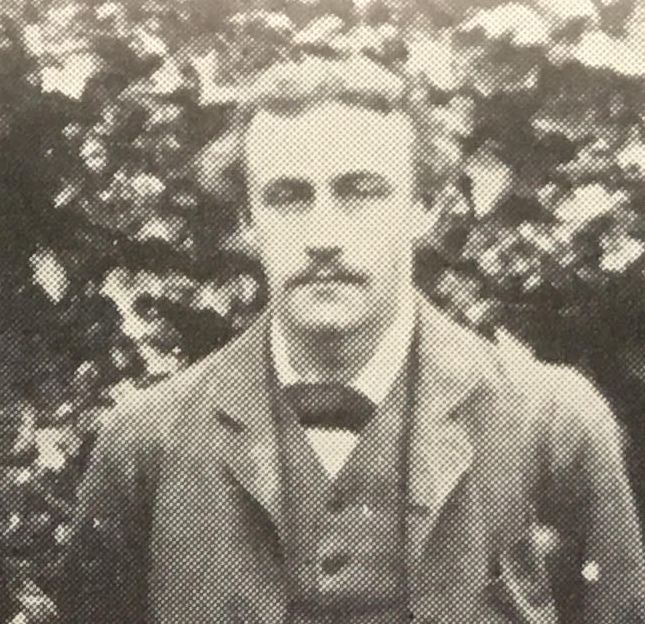

Antony Hope Hawkins (1883)

Antony Hope Hawkins (1883)

The lawyer, novelist and playwright, Anthony Hope (1863-1933)—born Antony Hope Hawkins (he dropped the surname and added the ‘h’ to his first name)—is remembered today as the author of The Prisoner of Zenda (1894) which added Ruritania to our imaginary map of the world. But the reason he interests us is that he was the President of the Russell Club when Morris told Oxford he was a socialist, and it was him, rather than Ruskin, or Bright—or, as some scholars have said, Benjamin Jowett (who probably wasn’t even there)—who chaired the meeting, a fact firmly established by Tony Pinkney.

In the fourth chapter of his autobiography, Memories and Notes (1927), Sir Anthony Hope recalled the circumstances in which Morris went to Oxford to speak to the members and guests of the Russell Club. Describing himself as being on the “Left” of the Liberal Party, like Morris he wore a red tie and like Sadler he grew his hair long.

Sadler, Hope, and J. A. Spender (about whom, more later) were all part of “a little coterie of about a dozen men of whom half were of Balliol” (like Hope and Spender), and “the rest chosen as kindred spirits from outside” (like Sadler). They met to discuss social problems in the rooms of the group’s founder, Arthur Acland (1847-1926), the son of Sir Thomas Dyke Acland (1809-1898), one of the two original trustees of Ruskin’s Guild of St George. Sadler’s son claimed that among the members of a group Acland formed in 1884 called the “Inner Ring” were himself, Hawkins, and Spender, and also Cosmo Lang, Leonard Hobhouse and Charles Mallet (see Sadleir: 68).

The Russell Club, founded as a radical alternative to the Palmerston, was destined to make a mark by inviting controversial guests to address its meetings. Hope sketches the background:

“I was a Home Ruler before Gladstone; I faced the obloquy incurred by the doings of the Land League; I even entertained in my rooms such firebrands as John Dillon and Michael Davitt, when they came up to address the Russell Club. Politics apart, Davitt was an attractive and interesting man. He talked of the days of his imprisonment; his prevailing memory of it was of being ‘always hungry and always cold’. And he told us, incidentally, that of all the convicts with whom he had come in contact, when a convict himself, the Tichborne Claimant was the most degraded and vicious.”

Among other speakers at the Russell Club was the Irish Nationalist politician and journalist, A. M. Sullivan (1829-1884).

In this context Hope describes Morris as “[a]nother apostle of another unpopular cause”. He continues:

“It is odd to remember that we had great difficulty in getting a place for him to speak in; nobody would harbour us, until at last University College gave us its hall. I, as President of the Club, had the honour of taking the chair for our guest. He was to me very impressive—a big-framed man, in a very loose suit of rough blue serge, with a magnificent head. But I am afraid that he did not enjoy the meeting much. His speech went well, but afterwards two or three political economy dons heckled him severely on points of detail, and it was evident that these pinpricks rather puzzled and distressed him. He seemed not to understand how men could meet his beautiful vision of a regenerated society with such petty cavilling. But he stood out as a great man; there could be no mistake about that, any more than there can be to a reader of Mackail’s life of him.”

Whatever the controversy surrounding the meeting, it did Hope no harm, and within a couple of years he was President of the Oxford Union, a relatively rare achievement at that time for a Radical Liberal.

Though Hope does not mention Ruskin in relation to the Russell Club meeting, his memoirs do include an account of an amusing encounter with Ruskin which it is appropriate to relate here, not least because it seems to have escaped the notice of Ruskin scholars. Four or five of the students like Hope who were reading for Greats at Balliol used to read their essays after dinner to the Master of the College, Benjamin Jowett (1817-1893). “One evening”, Hope recalls:

“Ruskin had been dining with the Master; he was staying in Oxford then, not, I think, very well nor with all his old powers, but a gracious and charming presence, with his courtly manners and his beautiful blue eyes matched generally by a big blue necktie—the match too good surely for mere accident! There was on the table—indeed there generally was—a dish of what they call French prunes, and Ruskin fell to praising the prismatic hues of the French prunes. We were delighted, of course, to hear the great man talk about anything, and did not mind for how long or in how highly coloured language he descanted on the French prunes.”

“But”, Hope adds, continuing his musical metaphor, “the Master sat slapping his lips together”—a habit of Jowett’s when he was irritated: “when Ruskin had bidden us goodnight and was gone, the treble voice said, ‘He’s generally right on moral subjects. And now the essays, please.’”

Before abandoning Hope (so to speak), I want to pause to note that one of Anthony Hope’s cousins was the beloved author of The Wind in the Willows (1908), Kenneth Grahame (1859-1932). The influence of News from Nowhere (1890) on that pastoral novel is perhaps obvious, and Grahame was a keen reader of Morris. A paper—or even a blog—on Grahame and Ruskin would make for fascinating reading. Given Grahame’s celebration of the English countryside, it is not surprising to discover that he enthusiastically devoured the work of Ruskin. Both men were friends with the formidable Frederick Furnivall (1825-1910), and it was probably through Furnivall that Grahame became involved with the work of the Ruskinian Toynbee Hall, the university settlement in Whitechapel named after Ruskin’s disciple and Sadler’s hero, Arnold Toynbee.

It is also worth mentioning here that Kenneth Grahame’s brother-in-law was Courtauld Thomson (1866-1954). At Eton, Thomson came under the influence of H. E. Luxmoore (1841-1926), who from 1920 to 1925 served as the fourth Master of Ruskin’s Guild of St George. After Luxmoore’s death, Thomson himself became a Companion of the Guild, and subsequently served with the educationalist (John) Howard Whitehouse (1873-1955) as one of the Guild’s Trustees. Thomson’s step-family, the Moultons, who influenced the Thomsons greatly, were also intensely interested in Ruskin’s work and ideas. In this year of political upheaval which has seen four different Chancellors of the Exchequer within a few months, it is also worth remembering that it was Thomson who gave the Dorneywood estate to the nation, a government property most often used by Britain’s chief Finance Minister.

J.A. SPENDER

J.A. Spender (1883)

J.A. Spender (1883)

To conclude this first part of our blog, we come to John Alfred Spender (1862-1942), best remembered as E. T. Cook’s successor as editor of the Liberal Westminster Gazette, a post he filled from 1896 to 1921. In 1927 he recalled in his memoirs Morris’s lecture at Oxford, and Ruskin’s role in it.

“The Russell Club, then, as now, an undergraduate Radical Club, of which I was at one time President, invited William Morris to deliver a lecture. He took as his subject ‘Art and Democracy’, and we induced the Master of University to lend the College Hall as a suitable place for a lecture on art by an eminent poet and man of letters. Morris did lecture on art for five minutes, but he also lectured on Socialism for fifty-five, to the scandal of the Master and the eminent company of Heads of Houses and dons, who had come at our invitation to pay a compliment to the poet. The Master got up in a great fume the moment the poet sat down, and said that if he had known how the hospitality of the College was going to be abused, he would never have lent the hall. At this Ruskin uprose and chaffed them all off their heads in a speech brimming with humour, and ending with a rapturous description of a sunset, which made everybody feel ashamed of having disapproved of Socialism.” (Spender: 20-21)

Spender’s account most closely accords with the long footnote published by Cook and Wedderburn in volume 33 of the Library Edition of Ruskin Works. In “an impromptu and unreported speech, chaffing these grave and reverend signiors freely”, Ruskin ended up “by some transition of thought no longer recoverable, with a description of a sunset” (Ruskin: 33.390n). Given that Ruskin was seconding a vote of thanks, his speech can hardly be said to have been “impromptu”, however, and it was at least partially reported and—curiously, given their claim that it was not—at least some of Ruskin’s words as reported are quoted by Cook and Wedderburn themselves, as we have seen.

Spender’s account seems rarely to have been specifically cited by scholars and yet most scholars seem to have based their version of events upon it. His rhetorical flourish about Morris speaking on art for only five minutes, and on socialism for 55, is demonstrably inaccurate, and the extent to which Ruskin smoothed ruffled feathers is debateable, not least because contemporary sources reveal that the sequence of speeches ran thus: Hawkins introduced the lecture, Morris lectured, Talbot (the Warden of Keble) gave the vote of thanks, Ruskin seconded him, Morris spoke briefly in reoky, Hawkins then thanked the Master and Fellows of University College for the use of the room, and Bright (the Master of Univ.) spoke last to distance himself from any notion of having permitted a political lecture. Bright nevertheless sought to justify the Fellows’ decision to host the event on the grounds that students should be exposed to a multiplicity of different views, including ones liable to cause controversy—a point that speaks loudly to ongoing debates in our own day. At some point—presumably immediately on completing the lecture—Morris took questions, some of which were apparently hostile, as Hawkins and Spender indicate.

Let’s end with another anecdote about Ruskin that Spender shares in his memoirs. It gives us a charming glimpse of Ruskin in the Drawing Schools in the early 1880s. (It is a lengthy paragraph which I have split into three in order to make it easier to read on screen.)

“The hours spent with Ruskin are among the pleasantest of my Oxford memories. He was then Slade Professor (for the second time), and nearly the whole time I was up, I attended the drawing-school on two afternoons in the week.

“It was no necessary part of his duties to teach undergraduates to draw—for there was an excellent teacher, Macdonald, to do that part of the business—but he loved to come to the school and give his own kind of instruction. Once or twice he sat down beside me, while I was copying a Turner drawing, and taking the brush from my hand, practically did the whole thing himself, accompanying the lesson with a stream of talk which, starting from Turner, flowed on to Shakespeare, Plato, and the Bible. Then he would take two or three of us a round of the Turner drawings in the Taylorian Museum, discoursing with the old enthusiasm about his favourites.

“On one of these occasions he said dogmatically that Turner never painted a flower in his pictures, at which I somewhat impertinently crossed the room and pulled out a drawing in which a small thistle in flower was perfectly painted in the foreground. He said decisively and finally that a thistle wasn’t a flower—which was what I deserved. On another occasion he defied us to find any architectural drawing of Turner’s which was faulty in perspective. This was a fair challenge, and I took one and proceeded to measure it and proved incontestably that it had no vanishing point that worked. This he admitted, but he had his revenge, for the next subject which he set the class was to put opposite rows of hexagonal pillars (of which he drew the first two himself) in a true perspective. This devastated the class, and when next he told a lady water-colour student that he would have ‘none of her damned washings-out’, we were nearly broken up. All the same I do not think that an amateur could have had a better sort of instruction than he got from Ruskin and Macdonald in those years.” (Spender: 19-20)

In my next blog, I will look at some of the contemporary responses to Morris’s Russell Club lecture, one of them truly dramatic…

SOURCES

Books

Anthony Hope Hawkins, Memories and Notes (London: Hutchinson, 1927)

William Morris, The Collected Works of William Morris, ed. May Morris (24 vols) (London: Longmans Green and Company, 1910-15)

John Ruskin, The Works of John Ruskin, ed. E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn (39 vols) (London: George Allen, 1903-12)

Tony Pinkey, William Morris in Oxford (Grosmont: illuminati, 2007)

Michael Sadleir, Michael Ernest Sadler: A Memoir (London: Constable, 1949)

Edith Hope Scott, Ruskin’s Guild of St George with a preface by Michael E. Sadler (London: Methuen & Co., 1931)

- A. Spender, Life, Journalism, and Politics (2 vols) (London: Cassell & Co. Ltd, 1927)

Newspaper/Journal Articles

“Mr William Morris on Art and Socialism” in Pall Mall Gazette (15 November 1883) 4

The Cambridge Review (21 November 1883) 98

“Mr William Morris at Oxford” in The Oxford Magazine (21 November 1883) 386

Please send feedback to contact@stuarteagles.co.uk