Between August and October 1887 Ruskin was in Folkestone. He purchased some drawings of the town as it looked earlier in the century, but resisted appeals to give them to the local museum. This blog sheds new light on the episode.

RUSKIN AND FOLKESTONE

Ruskin arrived in Folkestone on England’s Kent coast at the end of August 1887. He moved two months later to the neighbouring resort of Sandgate which he made his home until early June 1888. He was there during another difficult bout of the persistent mental illness that increasingly debilitated him in his old age. He had spectacularly fallen out with Joan Severn, his cousin and de facto carer, and the housekeeper at his Coniston home, Brantwood. Sone physical distance between them was essential.

In November, an American journalist visited Sandgate and interviewed Ruskin. The resulting article, dated 22 November, appeared the following January in the pages of the Boston Evening Transcript under the title, “Ruskin at Close View. An Interview with the Great Critic at Sandgate”. It was reproduced, lightly edited, in the Library Edition of the Works of John Ruskin (vol. 34, pp. 671-673) under the title, “Ruskin at Sandgate (1887)”.

Devonshire Terrace, Sandgate, with the back of the

Devonshire Terrace, Sandgate, with the back of the

Kent Hotel in the distance.

The interview took place at “an old-fashioned hotel, whose living-rooms look directly on to a shingly shore”. This was the (Royal) Kent Hotel, which fronted the High Street, but backed on to the beach and overlooked the English Channel. Ruskin looked well.

“There was no sign of weakness as he advanced and with kind cordiality greeted his visitor, pointed out a comfortable chair, and alluded en passant to the charming quaintness of the room. ‘It is so quiet,’ he remarked, ‘nothing but the sound of the sea, a murmur of waves, a rest and a pleasure.’”

The journalist began by referring to a newspaper report he had read in which it was noted that Ruskin had recently purchased “some water-colour drawings by Turner, of Old Folkestone”. Ruskin smiled and replied,

“That is not quite true, though of course there is a foundation for it. I bought some drawings from a Mr Barrow, of Old Folkestone, intending to use them as illustrations in a forthcoming book, depicting this coast in the days of Turner—you may know that Turner lived at Margate and painted all along this coast.”

The proposed book, as Ruskin’s editors note, was one of many that never came to fruition.

Ruskin’s answer is potentially confusing. If the drawings had belonged to “a Mr Barrow” his identity remains unclear. They were bought from a Mr Fetherstone, though he may merely have acted as the agent. The evidence for this is supplied in the columns of the Folkestone Express, Sandgate, Shorncliffe & Hythe Advertiser. Cook and Wedderburn do not quote it, and as far as I know, Ruskin scholars have not pursued it until now.

On 17 September 1887 the newspaper referred to “half a dozen views of old Folkestone, on view in the shop of Mr Fetherstone”. A little digging reveals the seller to be William Fetherstone (1840-1907), a local carver and gilder with a shop at 55 High Street, who since the early 1850s had sold artists’ materials, and cleaned, repaired and framed pictures of all kinds.

A week later (on the 24th) the Express reported that the notice about the drawings had been brought to the attention of Professor Ruskin, who was known to be residing at the Paris Hotel in the town. Readers were told that Ruskin “sent for the sketches and at once purchased them”.

The American article does not make it clear whether the drawings were by Turner.

They were not.

It is to the Folkestone Express that we must once again turn in order to discover the identity of the artist responsible for these watercolour drawings. This, too, is evidence that was not cited by Cook and Wedderburn, and it seems not to have been spotted by subsequent scholars.

The relevant information is in a letter addressed to the editor of the newspaper by the artist Felix Joseph (1840-1892), who at the time was staying at the Cavendish Hotel in Eastbourne, about 44 miles along the coast. His letter was dated 14th September (though presumably, given the established chronology, it should have read the 24th). It was published in the issue of the 28th. Joseph referred in his letter to the “water colour drawings of Old Folkestone, by George Barnard”.

George Barnard (1807-1890) was an artist, writer, and from 1843 to 1880, the drawing master at Rugby School. As such, some of Ruskin’s Hinksey diggers, many of whom were alumni of Rugby who went on to study at Balliol College, would have received their first instruction in art from him. There are no references to Barnard indexed in the 39 volumes of the Library Edition of Ruskin’s Works. Yet, in common with Ruskin, Barnard had been a pupil of the landscape artist, J. D. Harding (1798-1863), and was a prominent member of the Alpine Club. When The Alpine Journal published its obituary of Barnard, it stated:

“There was a time when Barnard was almost the only Alpine artist whose drawings could be looked at with pleasure by those with any respect for truth in mountain form. Turner’s example and Mr Ruskin’s preaching had fallen on stony ground, and the climber who went to a picture-show was at a loss to recognise the peaks he knew in the bulbous or umbrella-shaped monstrosities […] in those days [that] were not only individually, but generically, false; they were not only unlike the particular mountain they claimed to represent, but any possible mountain.” (The Alpine Journal, no. 110 (November 1890) p. 282)

In addition to his Alpine scenes, Barnard drew views of Switzerland, Wales and southern England, and made a series of drawings of Rugby School. He exhibited widely, including at the Royal Academy from 1837 to 1873.

Among the books he wrote, most of them based on his lectures at Rugby, the most important were probably The Theory and Practice of Landscape Painting in Water-Colours (1871) and Drawing from Nature. A series of progressive instructions in sketching, to which are appended lectures on art delivered at Rugby School (1877). He quoted from Ruskin approvingly in his writings, particularly in the latter of these two volumes in which he commended the first volume of Modern Painters (1843) written, as he put it, by “Turner’s eloquent advocate” (p. 184). Elsewhere, also with reference to Turner, he wrote of “the eloquent word-painting of Ruskin” (p. 215). Having celebrated the great benefit to the British public of receiving the Turner Bequest, Barnard wrote:

“while Turner possessed this grand power of teaching and influencing Art and artists by his brush and pencil, he has had the great good fortune to gain for an exponent of his thoughts, his feelings, and intentions, that most eloquent writer on Art, Ruskin, who, while Turner poured forth his soul and poetry in form and colour, translated and diffused it almost with equal force in words. Thus I consider Turner and his works to have influenced, in the highest degree, the artistic mode of studying from Nature, and landscape-painters in particular ought to reverence him, for he gave such an impetus to the appreciation of this branch of Art that has placed it side by side with the more popular study, the figure; and he must be regarded as having, by his works, during a long life, eminently assisted in raising the British school of painting to its present acknowledged character of supremacy both at home and abroad.” (p. 214)

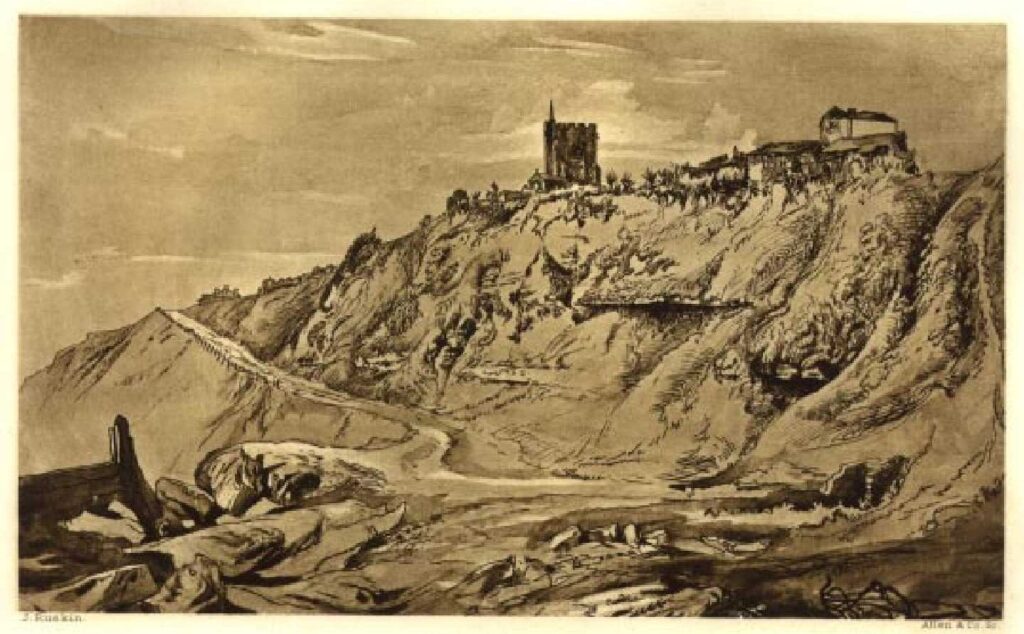

Some of Barnard’s views of Folkestone, which appear to have been executed in the early 1830s, and focus mainly on the harbour, were lithographed in the 1880s and used to illustrate the second edition of [John] English’s Reminiscences of OId Folkestone Smugglers. Whether the drawings Ruskin purchased were among them is not clear.

When it was reported in the Folkestone Express that Ruskin had purchased the drawings, it was noted with regret that they had not been bought by the town and that “the opportunity of securing them” had now been lost. An opportunity for self-advertisement was not missed, though: the paper shamelessly added, “There is a lesson to be learned, however, and that is, if one has anything to sell, he has but to announce it in the Express”.

The notice had certainly struck Felix Joseph who, like Ruskin, had been fired into action. “Recognising how desirable it would be that such records of the past should become public property”, he explained

“I instantly put myself in communication with the owner, and determined to buy these drawings and present them to the Local Board at Sandgate. I also wrote to Mayor Fynmore, informing him of my intentions, and asking him to report to me on same. This he was polite enough to do, and I learnt with much regret they had been disposed of to Professor Ruskin.”

Joseph was too late, but he had not given up hope of securing them for the town.

“My object in troubling you with these few remarks is to suggest that some one should write to Mr Ruskin, and endeavour to induce that gentleman to present them to your new museum. Perhaps if properly approached he might do so, as the drawings in question would be of the very greatest interest to the town, and no effort should be lost to try and secure them.”

It appears that nobody did approach Ruskin, but Joseph’s letter was pointed out to him and it provoked him to respond on 30 September. His letter was published by the Express on 5 October, and it was reproduced by Cook and Wedderburn in the Library Edition under the title, “Old Folkestone” (vol. 34, pp. 610-11):

“My attention has been directed to the letter in your issue of the 28h […] to which I can only reply that as now Folkestone has sold all that was left of old Folkestone to the service of Old Nick—in the multiform personality of the S. E. Railway Company—charges me, through said Company, a penny every time I want to look at the sea from the old pier, and allows itself to be blinded for a league along the beach by smoke more black than thunder-clouds, I am not in the least minded to present new Folkestone with any peeps and memories of the shore it has destroyed, or the harbour it has filled and polluted, and the happy and simple human life it has rendered for ever in the dear old town impossible. The drawings were bought for better illustration of Turner’s work and my own, on the Harbours of England, and will, I hope, therefore be put to wider service than they were likely to find in Folkestone Museum.”

This outburst of unfiltered invective was not calculated to endear him to his temporary hosts and may in part explain why he moved the short distance to Sandgate at the end of October. (He had also erupted into violence in his Folkestone hotel, and provoked controversies of a more personal character.)

It was uncharacteristic of Ruskin effectively to punish the people of Folkestone for the sins of its municipal authorities and commercial exploiters. At the same time as he struck this attitude in Folkestone, and among other uncommonly generous acts of philanthropy, he paid £1,000 for the 130-carat uncut diamond found in South Africa which he presented to the British Museum and named the Colenso Diamond, in honour of his friend, the first Bishop of Natal. On display there for nearly 70 years, the diamond was stolen in 1965 and has never been recovered.

John Ruskin, “Old Folkestone” (1849)

John Ruskin, “Old Folkestone” (1849)

The fact that Ruskin purchased the drawings with a book in mind partly explains why he was determined to keep them close. The explanation accords with what he had told the American journalist, who went on to ask Ruskin about the report that “the Town Council, or some of the local magnates of Folkestone” had asked him “to present the drawings to their museum”. Ruskin confirmed that this was true, and elaborated on the points he had made in his letter: “they would not appreciate them if they had them”, he insisted.

“They are doing all they can to spoil the beautiful coast and the old town with their horrible railway erections; there are steamers there spouting smoke for three hours before they start—one would think they might save their fuel; however, that is their lookout, though the thing is monstrous. Once one could see the lovely coast stretching to Dover, see Shakespeare’s Cliff; now that is all hidden by hideous smoke. To think that I should give them the drawings, that they might have bought themselves had they been so minded, they are the damnedest people.”

The journalist did his best to cushion the impact of Ruskin’s words by asserting that the critic’s “way of saying the word ‘damnedest’ does not strike one as a condemnatory epithet; it is said with such a gentle relish, that it merely becomes a superlative adjective of a humorous tendency”.

This is well put. Many readers misinterpreted Ruskin’s humorous writing. They took his exaggerations too literally or failed to understand the serious point that lurked beneath the jokes. It was a difficulty that seldom arose when Ruskin was in conversation or giving a lecture.

Ruskin was, of course, entirely serious in his underlying criticism of pollution, and his phrase about saving fuel is striking. Later in the interview, Ruskin “drifted conversationally to the Folkestone people and their contrivances for defacing Nature’s handiwork”. He could see the way the world was tending, and he did not like it one bit.

“They are even talking of sending their smoking steamers here [to Sandgate], building a pier and a railway and I don’t know what—whatever they touch in Nature they surround and spoil. There is a man there who has bought a bit of lovely moorland and gone and built a wall around it! The beach here is well as it is, and should be left so. Not that they appreciate it; it serves for the lovers who come from there, and sit on the shore in their horrible plaid costumes and gaze on the sea.”

Later on, talking of Ireland, Ruskin condemned Britain’s “obstinate and cruel Government! Nothing but cruelty and oppression in Ireland, beginning with Henry VIII.” The interviewer replied, “But you do not blame the existing Government for follies of the past?”

“No”, Ruskin answered, “but the existing Government has its follies of to-day. Let it redress these.”

Ruskin speaks to us still, and with greater force of reason than ever.

Please send feedback to contact@stuarteagles.co.uk