Edith Hope Scott was one of Ruskin’s most devoted and active disciples. St George’s Day in the year in which we celebrate the 150th anniversary of the Guild of St George seems an appropriate moment to remember her.

Scott was one of the people who banded together in January 1883 to form a new Ruskin Society in Liverpool with the object of promoting the study of Ruskin’s writings and the practical adoption of his ideas. She was also among the earliest Companions of the Guild of St George, founded by Ruskin to battle the ugly and rampant dragons of urbanisation and industrial capitalism. Among the Guild’s antidotes to modernity were the revival of creatively fulfilling traditional handicrafts and the sympathetic renewed of rural life. Scott was at the forefront of both. She learnt how to spin and weave by hand and taught others to do so, establishing a cottage industry in Liverpool producing linen. And she spent long periods living and working in the English countryside. Above all, what most mattered to her—and Ruskin—was education. The briefest summary of her biography reveals what a thoroughly Ruskinian life she led.

Scott’s family settled in Liverpool when she was young. They lived in a house called Atholfeld in Cressington Park, Scott’s main home nearly all her life. It was there, in the last years of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, that she ran a successful preparatory school for girls. It was work in which she was assisted by her sister Lilian (1869—1954). According to Scott’s obituary in the Runcorn Weekly News, “among her correspondents [in later years] were many who had passed through her hands”. After she gave up the venture, she joined the Board of Management of a group of local schools in Garston. (She was also on the committee of the Liverpool Hahnemann Hospital, a facility on Hope Street that specialised in homeopathic medicine.)

Scott was born on board a ship navigating a storm in the Cape of Good Hope. The vessel in which she entered the world was captained by her father, David Scott (1831—1908). In choosing to commemorate the circumstances by giving their daughter—and first child—the middle name of Hope, David Scott and his wife Eleanor Burgess neé Hayward (1835—1921), christened her with the optimism that would underlie a lifetime of good work.

Captain Scott was a huge influence on his daughter. In the outline of his life can be discerned many of the principles and interests that guided Edith. He was born in Cupar, Fife. As a master mariner who first commanded the seas at the age of 24, he went all over the world in all manner of ships, sometimes with his family in tow. He went to America, Australia, the Far East and most places in between, sometimes on trade, sometimes transporting passengers, and in 1867 even shipping supplies to war-torn Abyssinia (Ethiopia). The 24 years of his retirement were spent in an active and cheerful life in Liverpool. He was a devoted member of Rev. Thomas Cole’s ministry at Garston Congregational Church, and he was a keen member and sometime Chairman of Aigburth Liberal Association. He was also engaged in social work, helping local boys’ clubs, for example.

Edith Hope Scott became an enthusiastic disciple of Ruskin in her youth, and she was not alone in her family in doing so, or in remaining loyal to Ruskin’s ideals to the end of her life. The Scott family tree blossoms with the names of men and women who joined the Liverpool Ruskin Society and became involved with the Guild of St George, most notable among them her brother-in-law William Wardle (1858—1925), a tinplate merchant who became Secretary of both.

Scott’s most important contribution to the work of the Liverpool Ruskin Society was to initiate, around the year 1901, a class to teach local blind girls how to spin. Scott was assisted by other ladies in the society, including Annie Nicholson, who worked at the local blind institution, and Jessie Richmond, who would later produce hand-spun linen in Anglesey. Together they weaved a modest quantity of useful if somewhat coarse home-spun linen for household purposes which the society sold. The Annual Report for 1903 noted that in the previous 21 months, 36 yards of linen had been produced. By the summer of 1913, the Liverpool Ruskin Society was in a position to exhibit some choice specimens of their linen and lace work in the Arts & Crafts section of the major city exhibition. According to the Liverpool Daily Post Scott and her friends even gave demonstrations of spinning and weaving to visitors (30 May 1913). Only the First World War brought this work to an end.

In 1908, the year in which her father died leaving her a substantial share of his £10,000 fortune, Edith began to spend part of her time living at Atholgarth, a cottage in Bewdley, in the Wyre Forest. She lived next to land first colonised by the Guild of St George in the 1870s and was part of a group of Ruskin disciples from Liverpool which helped revivify this small Ruskin community in the first third of the twentieth century. Their story is ably traced by Neil Sinden and can be read here. See also Peter Wardle and Cedric Quayle’s Ruskin and Bewdley.

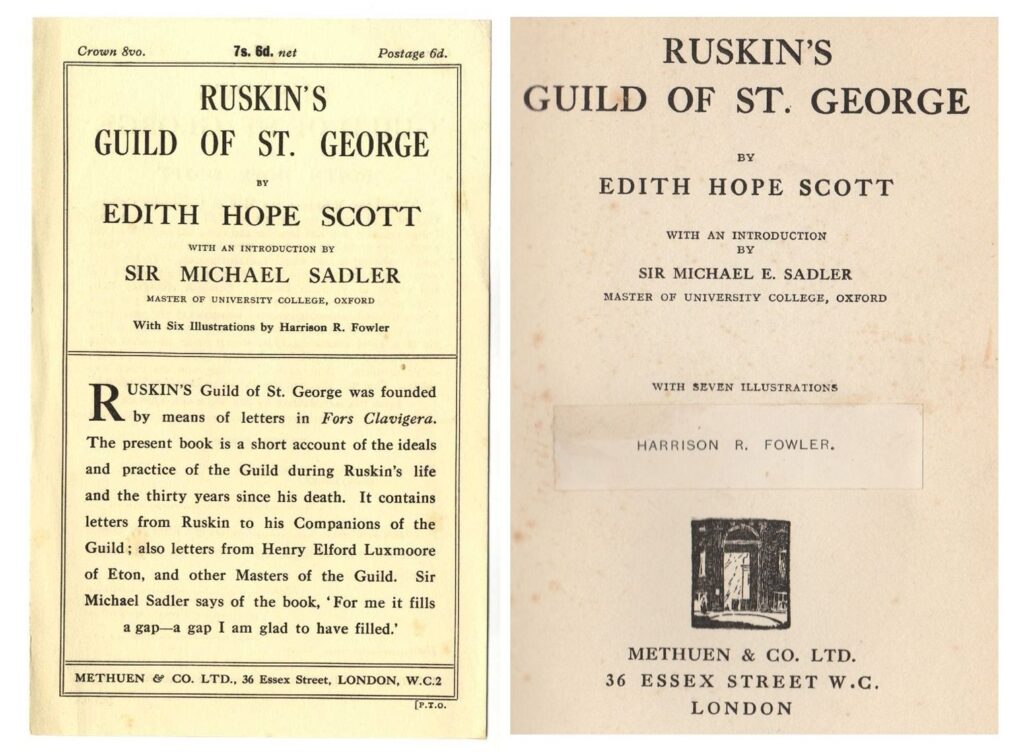

Scott was a prolific writer. Her obituary states that she “wrote wisely and well. Her letters, which fell ‘thick as autumnal leaves’ among her friends, were always strong with her personality and sparkled with witty allusions and quaint sidelights on topics of the day.” Her published writings, mostly short fiction and poems, met with only modest success, but they possess the simple and unassuming charm characteristic of their author. Among her books were The Stretcher Bearer, Mistress Reality, With the Eyes of a Child, With Feet of Wool, the Mother Holda Stories, The Holy Mountain and other Verses, and The Beloved, the last of these a rural idyll set in the Wyre Forest. Some of her stories were read on BBC radio. On 30 October 1936, shortly before her death, for example, her short story “Bank Holiday in Whipsnade” was read on The Children’s Hour. Her very personal study, Ruskin’s Guild of St George, was the first attempt to chronicle the history of that organisation. Like much of her work, it was illustrated by her brother-in-law, the Liverpool painter and printmaker, Harrison Ruskin Fowler (1876—1962).

In the judgement of the Runcorn Weekly News Scott’s death “removed a gracious personality from the life of Garston and Grassendale and from the literary circle of Merseyside”.

“A correspondent has written an appreciation which records that none of those who knew her will ever forget her vivid and tonic personality. […] To quote a friend who knew her well, ‘Edith Scott had a beauty and purity of intellect and soul which is seldom surpassed.’”

*****

I have long been an admirer of Edith Hope Scott, ever since I read her history of the Guild, and found out about her work with the blind girls of Liverpool. I appreciate the unpretentious simplicity of her fiction and poetry, and the quiet devotion of her social work. In 2018 I visited Toxteth Park (Smithdown Road) Cemetery and—thanks to excellent local record-keeping—and the eagle-eyes of my family, I found the beautiful gravestone which celebrates Captain Scott’s life on the seas. The stone also memorialises Scott’s wife, and his two unmarried daughters, Edith Hope Scott and her sister, Lilian. Just a few steps away is the grave of William and Violet Wardle, but that is a story for another day. In sharing these photographs of the Scotts’ gravestone I invite you to remember Edith in particular and to celebrate her contribution to Ruskin’s legacy.

Please sent feedback to contact@stuarteagles.co.uk

PRINCIPAL SOURCES

“Proposed New Ruskin Society” in Liverpool Daily Post (8 January 1883) and Liverpool Mercury (9 January 1883).

“Funeral. Captain Scott, Cressington” [Obituary] in Liverpool Daily Post (15 May 1908).

“Miss E. Scott, Grassendale” [Obituary] in Runcorn Weekly News (18 December 1936).

T. Porter, “The Spinning-Wheel in Liverpool” in Saint George, vol. 11, no. 42 (April 1908) pp. 126-131.

Neil Sinden, “Ruskin Land: The Evolving Story” [online].