“An excess of modesty and bashfulness”:

the first meeting of Ruskin’s Guild

Stuart Eagles

To Annie Creswick Dawson,

Guild Companion and Dear Friend

No detailed account of the Guild’s inaugural general meeting has ever been published. Until now. For the first time, all of the people known to have attended this crucially important coming-together of Ruskin’s disciples will be fully identified. In reconstructing the event, the words that many of the participants were inspired to speak have been recovered.

Ruskin’s usually diligent editors, Edward Cook and Alexander Wedderburn, were vague and inaccurate in volume 30 of the Library Edition of Ruskin’s Works, telling readers in a “Bibliographical Note” to the Master’s Report of 1879 that:

“The first meeting of the Guild of St George was held at Birmingham early in March 1879. In Ruskin’s absence, the Report here given [reproduced on pp. 15–22 of the volume] was read by the chairman of the meeting, Mr George Baker.

“An abstract of the Report, with some textual quotations, appeared in the Spectator of March 22, 1879 (p. 368), in an article entitled ‘Mr Ruskin’s Society’.”

—Ruskin, Works, vol. 30, p. 14.

Contemporary newspaper reports, archive correspondence and Guild minutes reveal that in fact the meeting took place on the afternoon of Friday, 21 February, at the Queen’s Hotel, Birmingham. Ruskin was indeed absent, but while it is true that the meeting was chaired by senior Guild Companion, George Baker, Ruskin’s report was in fact read by the curator of the Guild’s museum in Walkley, Sheffield—Henry Swan.

OPENING REMARKS

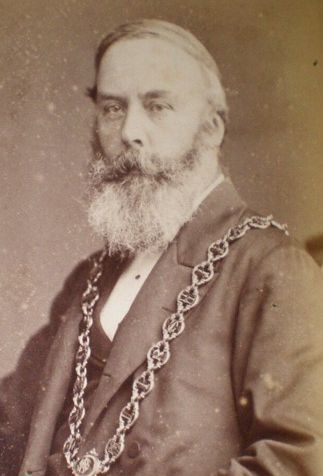

Alderman George Baker (1825-1910) (pictured above), a former Liberal Mayor of Birmingham, and a prominent Quaker blacking manufacturer, made it clear in his opening remarks that he had been called upon at short notice to preside. Consequently, he would not be making a speech, nor would he attempt to explain the objects of the Guild, though he expressed the hope that others would do so. In making the arrangements for the meeting, however, he had read several of Ruskin’s recent letters and he proceeded to read certain extracts from them.

In a letter of 12 January, Ruskin, who had suffered a serious mental breakdown in the previous year, had written, “I cannot, in the present state of my health, attend any general meeting myself, or do anything but the most straightforward business.” Ruskin had written in another letter that all he really wanted for the Guild was more members and land.

The most recent letter Baker had received from Ruskin had insisted that the main point of business at the meeting should be the appointment of trustees, and Ruskin named Baker and the Brighton brewer, collector and philanthropist, Henry Willett (1823-1905), as his choice candidates. In the event, Willett—who was not present at the meeting in Birmingham—declined the invitation, but Baker did become senior trustee until he succeeded Ruskin as Master of the Guild in 1900.

“[W]ill you please say to the meeting”, Ruskin urged Baker, “that I never contemplated any legal difficulties of the kind I meet with, and that I entirely decline any further responsibility in such matters? That the office of master, as defined in Fors, is one of authority over persons voluntarily rendering obedience to great principles, and not authority enforced by law as at present constituted, and that for all the organisation of the Guild they must appoint—or you, the trustees, must appoint—some clerk or secretary to be responsible, with direction from the solicitors, for I am virtually dead in all such business.”

MASTER’S REPORT

Henry Swan (1825-1889) then read Ruskin’s Master’s Report. A summary in the press captures the essence of Ruskin’s message, but also highlights the challenge Swan had to read aloud the long sentences that turned and twisted snake-like from Ruskin’s ophidian pen.

“In calling this meeting of St George’s Guild to their first ecclesia, their Master cannot but condole with them on the smallness of their numbers: nor would he at all desire them to take either pride or comfort in any sacred texts or accepted aphorisms concerning the value of little floods and efficiency of resolute phalanxes. He takes much blame to himself for want of clearness in expression of the work to be done, and he confesses not a little discouragement to himself with perceiving, even in cases where he has made the nature of it intelligible, how very unwilling most people were to have any hand in it. The radical cause of the general resistance to the St George’s Guild effort is the doctrine, preached for the last fifty years as the true gospel of the kingdom, that you serve your neighbour best by letting him alone, except in the one particular of endeavouring to cheat him out of his money. But the hurrahing and flinging up of caps, which throughout beatified Europe have hitherto attended the promulgation of the method of temporal and eternal salvation, are, as it seems to me, beginning slightly to abate in the presence of such unpleasant commercial incidents as the stoppage of the Glasgow Bank (of which a man of large social expression wrote to me that no such distress had fallen on Scotland since Flodden Field), and of the social discomforts—not to say distresses—which are beginning to manifest themselves as the results of picture wealth in England and military triumph in Germany. The guildsmen of St George now meet, therefore, at a time when they really hope to draw some attention to the possibility of yet more honourable conditions for trade in the future. ‘Trade’, or literally the delivery of goods by one man to another—there is really no nobler human vocation, provided the deliverer be sure the time he has delivered is a good, and that he make sure the thing he receives in return for it is a good also to himself, which it is too possible that it may not always be. Under laws of such intelligent commerce, the St George’s Guild, holding itself constituted, has yet a special work on its hands which is not a tradesman’s, and which, without, as just said, implying any essential dishonour in the inferior function, is yet to be thought of rather as divine than a human vocation—the securing, namely, of excellent quality not merely in the goods to be delivered, but in the persons by whom they are to be enjoyed—an object which the modern British public is, indeed, satisfied may be presently effected by the institution of its operatives in atheism and molecular development, and by its own industrious novel-reading, but which the British public will assuredly find to its cost and sorrow can only be effected in that old fashion which has been since the world was settled on its axis and its path—by training their children in the way they should go, and being sure, primarily, they are not out of that way themselves.”

Ruskin’s description of the Guild’s landed property then followed, namely:

- the Sheffield Estate, consisting of eight plots of land, together containing one acre, or 4,850 superficial square yards, with a substantial stone dwelling house thereon, in which the nascent collection of the museum is temporarily placed;

- the Bewdley Estate, consisting of 20 acres and six perches of land, in the borough of Bewdley;

- the Cloughton Estate, consisting of two pieces of land;

- the Mickley Estate, consisting of about 13 acres of land at Mickley, in the country of Derby;

- the Barmouth Estate, consisting of 3 roods 10½ perches of land, at Barmouth.

Ruskin reported that it was only to Sheffield that he had “been able hitherto to give any personal attention”. After “careful deliberation” he was “disposed to recommend” that the Guild’s lands “should be devoted wholly to educational purposes”. He therefore proposed that:

“as soon as the enlarging funds of the Guild may enable him, to place a building properly adapted for the purpose of a museum, with attached library and reading rooms, on the ground at Walkley; and to put the estate at Mickley under cultivation, with the object of showing the best methods of managing fruit trees in the climate of northern England, with attached greenhouses and botanic garden for the orderly display of all interesting European plants.”

The Bewdley Estate, Ruskin declared, was:

“in a beautiful part of England, in which the master, for his own part, would be well content that it should remain, for the present, in pasture or wood, a part of the healthy and lovely landscape of which so little remains now undestroyed in the English midlands. But he is well content to leave it at the option of one of their now succeeding trustees—Mr George Baker, of Birmingham, to whose kindness the guild owes the possession of this ground—to undertake any operations upon it which in his judgment seem desirable for the furtherance of the objects of the Guild. “

It was reported that the Guild had £5,000 vested in Consuls; and the Master sincerely hoped that the public, when once convinced that the purposes of the Guild were not “visionary”, may be:

“disposed to consider with itself whether, in the present conditions and prospects of commerce, it is not wiser to strengthen the hands of honest workers than to enlarge the sphere of speculation, and provoke the ever increasing horror of its catastrophes. The St George’s Guild may be able to advance but slowly, but its every step will be absolute gain; and the eternal principles of right on which it is founded makes its failure impossible.”

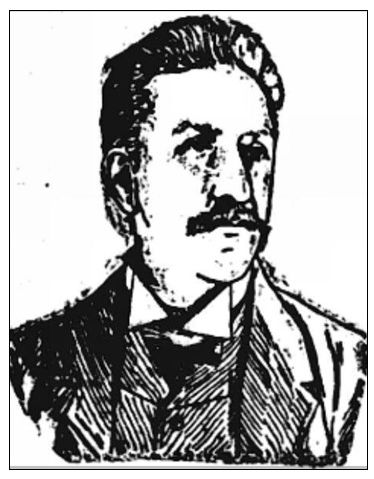

Baker then read out the accounts of the various estates, showing aggregate receipts of £7,271, 15s. 7d. including £778, 9s. 6d. in subscriptions. There was cash in hand to the amount of £669, 6s. 6d. Baker proposed the adoption of the report, and the motion was seconded by Companion Herbert Fletcher (1842-1895) (pictured below), the Bolton colliery owner, mining engineer and social reformer. The meeting was then opened up for Companions to discuss the reports and the Guild’s affairs.

THE DISCUSSION: I, THE GUILD’S ESTATES

Baker began the discussion by telling those present that on the Bewdley estate five out of the twenty acres of coppice had been cleared and was being planted with fruit trees set about sixteen yards apart, leaving sufficient open space for the purposes of pasture or arable farming. They planned gradually to extend the scheme across all 20 acres.

A little while later, William Buchan Graham (1846-1909), the working-class Companion engaged in physically carrying out the practical work on the Bewdley estate, confirmed what Baker had said, but added some rich detail.

“The number of young oak trees on the land had occasioned a great deal of labour. Since the potato crop the land had been drained, and fruit trees planted. At present there were about 120 of such trees.”

Fellow working-class Companion, John Guy (1845-1929), who tended the Cloughton estate near Scarborough, then said that he desired to give his testimony as to “the practicability of Mr Ruskin’s scheme”. It is almost certain that Guy’s letter reproduced on pages 22 and 23 of volume 30 of the Library Edition of Ruskin’s Works, and dated 21 February 1878, was in fact written for or immediately following this first general meeting on 21 February 1879. Guild Companions, Guy reportedly said:

“were often met with the statement that [Ruskin’s scheme] could not be carried out, and, as a working man, he thought he should like to try it. He looked out for as rough a bit of land almost as he could get, and as cheap. He had worked upon it with his wife for almost eighteen months, and though they had missed many of what were called town pleasures and conveniences, it had been counterbalanced by a greater degree of home happiness. They had not earned so much money, but they had found it possible to live and have a little store laid by. (Applause.) The Cloughton Moor estate was of about two acres in extent, and about 604 feet above the sea. He and his wife and children could live very nicely there, and, if it was Mr Ruskin’s wish, they should stay there.”

Mark Frost has exposed the painful reality of life for the Guy family at Cloughton Moor and has traced the sorry descent of the estate. (See Mark Frost, The Lost Companions (Anthem Press, 2014) pp. 180-188.) This new evidence from the Guild’s inaugural general meeting is significant in two respects: first, it suggests that Guy himself chose the Cloughton estate, and indicates that, at least at this stage—just eighteen months into the project—he was keen to present what would subsequently prove to be an overly rosy picture of the family’s life there.

Frost has painstakingly detailed the increasing struggles of William Buchan Graham at Bewdley, and his mounting sense of disenchantment with his treatment as a Guildsman at the hands of Ruskin and Baker (see Frost, The Lost Companions, pp. 119-123, 172-179, 183-188). Evidence from the meeting in February 1879 shows that Graham was already beginning to feel unhappy about his situation.

In response to John Guy’s observations, Graham told the meeting that:

“it must be very clear that one acre of land, only recently brought under cultivation, was scarcely sufficient to support a man and his family, and he understood that, as a matter of fact, Mr Guy had had to obtain occasional employment from others. He suggested that it would be better in the future for two guildsmen to work together, assisting and inspiring each other, rather than for one in the extreme west and another in the extreme east to be working in isolation, and, he might almost say, without heart.”

Guy seems to have felt that Graham had somewhat overreached himself in speaking on his behalf, even putting words in his mouth, and when he had an opportunity, Guy responded that:

“though isolated on the North-east coast, he did not wish it to be understood that he worked ‘heartlessly’. He was quite in the hands of Mr Ruskin and the Guild, and was willing to do whatever they thought desirable for the general welfare, but he had no doubt that, in his present situation, he could make a living by working for other people occasionally. He could quite understand that Mr Graham should feel some of the dispiriting effect of isolation, for he was a single man. (A laugh.)”

Graham is unlikely to have found Guy’s response encouraging, and it would not have helped that Baker chipped in with a joke at Graham’s expense: Mr Graham, he quipped, must find a “companion”. Laughter ensued. Graham may have taken this in good heart—no pun intended—but it is tempting to suppose that the seeds of what would prove to be his growing resentment were nourished by such public ribbing. It seems equally probable that Cook and Wedderburn were aware of these local newspaper reports of the first Guild meeting. They appear to have chosen not to reproduce or even refer to the reports because they were aware that the Guild had attempted to suppress misgivings about the treatment of Graham, Guy, and others, the details of which Frost eloquently sets out in his 2014 study.

Meanwhile, Henry Swan explained that Ruskin had chosen Walkley as the site for the Guild’s museum because it was the nearest spot outside Sheffield which was properly out of the smoke of the town. Ruskin had not intended the museum “to be used as a place to which nursemaids might take children to see stuffed lions”, he said, “but at which students might derive advantage and profit”. Swan stated that “in order to properly show its treasures” more space was required. “At the present time”, he added, “a valuable picture, by an old Venetian master, was locked up for the want of room to exhibit it.” Though the reports do not identify the picture Swan was referring to, it was clearly “The Madonna and Child” by Verrocchio, bought for the Guild at a cost of £100 a couple of years earlier. It would only be satisfactorily exhibited at the museum in Walkley when Ruskin visited later in 1879 in preparation for the visit by his former pupil, Prince Leopold, Queen Victoria’s youngest child.

THE DISCUSSION: II, THE GUILD’S OBJECTS

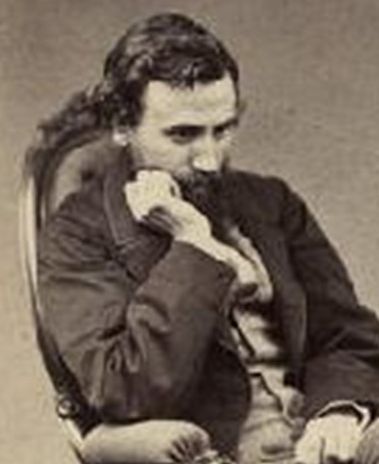

There was a definite shift of focus when the next speaker rose to his feet: Alfred William Hunt (1830-1896) (pictured above), the Liverpool-born artist associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. The main object of the Guild, Hunt asserted, apparently referring back to John Guy’s opening remarks, was “anything but an impracticable one” though he had often been puzzled to explain it, a comment which elicited shouts of “Hear, hear”. At least, he added, he was right in his assertion “if any movement which arose from a strong disposition to set things right by a definite course of action could be called practical”:

“Such a course of action really was necessary, for it was altogether impossible to travel through England without seeing how the country was being spoilt; and although he did not wish for a moment to alter the existing state of things in many respects—to prevent the extension of railways and similar works—he desired most earnestly to keep certain parts of the country intact. (Hear, hear.) If this present process continued nothing would be left from which any idea could be formed of what England once was, and he could bear his testimony as an artist to the fact that it was once the most beautiful country under the sun. (Applause.) The society had one good point, that it would found an agricultural university. (Hear, hear.) Mr Ruskin had shown his wisdom in making the Guild a very elastic one, for they did not bind themselves in becoming members to take any great share in its working; the society was very glad even of sympathy. (Hear, hear.)”

Mr Mackrell, of the firm of Messrs Tarrant and Mackrell, solicitors to Ruskin and to the Guild, explained that so long as nothing illegal was done in the way of division of profits, each member was liable only to the extent of £5. This caused the eminent Birmingham architect, J. H. Chamberlain, to clarify that the liability of any member of the Guild who held himself or herself altogether apart from any division of profit was absolutely limited to a liability of £5. Mackrell confirmed that this was the case. An unnamed Companion then said it was well to make it clear to outsiders that, “though the Guild for legal purposes was registered as a society, it was in no sense a society established for the purpose of yielding pecuniary profit to its members”. Baker referred members to Clause VIII of the Guild’s Articles of Association which, he remidned them, “jealously guarded against” members personally profiting from the organisation, and:

“expressly provided that, on the winding-up of the association, any property that remained should not be distributed amongst the members, but should be transferred to some institution or institutions having objects similar to those of the association. So that neither while the Guild was being carried on, nor when it was wound up, would the members derive any monetary benefit therefrom.”

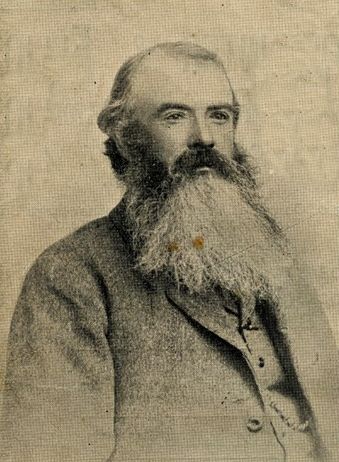

Egbert Rydings (1833-1912) (pictured above) of St George’s Mill, Laxey, on the Isle of Man, then explained that “for some time” he had been engaged “in the manufacture of material for ladies’ dresses, and had also supplied several guildsmen with cloth for trousers”. For reasons that are not altogether obvious, this provoked a laugh. “If ladies wished to learn to spin on the little wheel”, he added, “he should be happy to give instruction”. Baker responded that “ladies—or rather guildswomen—(a laugh)—would be glad to avail themselves of the offer”, though on what evidence he made such an assertion is unclear. According to some sources, Rydings then suggested that the Guild should devote its attention to one particular spot, so that the result of the work should be apparent, perhaps believing that his venture at Laxey should be made the Guild’s priority. “The present system of isolating the scenes of their operations was only bringing them into a sort of ridicule”, he thought. There is an obvious resonance here with Graham’s criticism.

At this point Ruskin’s report was adopted.

A SOUL IN SEARCH OF A BODY

Herbert Fletcher moved that Ruskin be elected Master of the Guild for life. He observed that the great difficulty they had in an undertaking of this kind was to reconcile Ruskin’s ideas with the practices of every-day people. He said that:

“the object of the society was to acquire possession of land to be employed in such a manner as would afford the people who obtained their livelihoods upon it their fair share of that pleasure and delight in existence which all were naturally constituted to experience.”

The architect John Henry Chamberlain (1831-1883) (pictured above), seconded Fletcher’s motion, and launched into a lengthy and moving monologue. He said he felt “just a little surprised at the course the meeting had taken, because he had an idea before he came that, if anything, they would have an excess of enthusiasm, whereas, so far, they had had what had seemed to him almost an excess of modesty and bashfulness.” Chamberlain would be appointed a trustee of the Guild alongside Baker later in the year. He told the meeting:

“It would be a pity if they did not express before they went away what he was sure they all felt—how deep, quite irrespective of St George’s Guild, was their debt of gratitude to Mr Ruskin. (Hear, hear.) He did not suppose there were any present who would not be ready to admit that they owed to Mr Ruskin more than they could ever repay him in words, or could describe to one another. Although this was not a meeting for the detailing of personal experience, he might perhaps be permitted to say that it was rather more than thirty years ago [sic] since the Seven Lamps of Architecture [(1849)] came upon him as light in the midst of profound darkness, as water in a land more than ordinarily desert and drear. From that time to the present there had not been a year, a month, a week, perhaps scarcely a day, of his life in which he had not felt straightened and bettered by the feelings derived from the reading of Mr Ruskin’s works, and the guidance which he had obtained therefrom. It was altogether out of the question, irrespective of gratitude, that they should elect any other gentleman than Mr Ruskin as the master of the Guild. They had tacitly confessed that most of them did not know what to do. Mr Ruskin, however, was in this position, that he knew what to do, and he wanted others to help him. The reason he (Mr Chamberlain) signed the Articles of Association was that he thought it a matter in which there was a soul going about asking for a body. He was perfectly content to take no more advanced a part in the society than this; that, so far as he could in any way assist Mr Ruskin, so far he would do so. He would not go and help Mr Graham; he could not do so. (A laugh.) He would not invade Mr Guy’s idyllic life; but, in whatever situation they might be, they could assist Mr Ruskin in the great work he had undertaken, and in which some of them had endeavoured to follow as best they might. In Birmingham they, at all events, felt this great truth—that occupation ought to be no bar to a man’s enjoyment of all the advantages that education and enlightenment could give him. They believed in the possibility of the noblest life to the working man and artisan as well as to the rich.”

Chamberlain would develop his thoughts about the influence The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849) had had upon him in a lecture he delivered later in the year. It will be the subject of the next blog.

Chamberlain then told the Guild meeting that he had been “much interested by what Mr Morris told them the other day with regard to his own experience of Iceland, where men, though poor beyond our idea of poverty, were scholars and gentlemen, and who, if they came over to England, would be able to talk about history to the first man they met.” Chamberlain was referring to the address the poet William Morris (1834-1896) had given two days earlier to the Birmingham Society of Arts and School of Design, of which Morris was President. Both Baker and Chamberlain were reported in the local press to be present at Morris’s lecture. Sent the printed version of the address by Georgiana Burne-Jones (1840-1920), Ruskin wrote to her (on 24 June 1879) of

“this superb address. I had not seen it, and read it at first in dips of delighted astonishment—thinking it was some new strong voice at Birmingham. Seeing then who was speaking, you will easily suppose I have some fault to find, and that grave—which may be summed in the finding two words wholly omitted in the address—those which Naboth was accused of blaspheming. [I.e. 1 Kings xxi. 10: “Thou didst blaspheme God and the King.”] Their omission is a form of blasphemy which certainly does not exist in Morris’s heart, and ought not to have been accuseable [sic] in his work. […]” (Ruskin, Works, vol. 37, p. 289.)

At the Guild meeting, Chamberlain went on to explain that “he was quite prepared to be laughed at” with regard to Ruskin’s Guild.

“They were not going to succeed at once in a path in which so many had failed. It was quite possible they would not succeed in doing all the things they desired, but it was only by repeated experiments and failures and yet keeping up, through all failures, the belief in their principles that they could ever hope to succeed. Those who felt indebted to Mr Ruskin could best repay him by giving him an opportunity of doing this work. He trusted that Mr Ruskin’s life would be spared to him for a great many years, and that this society would become that which he wished it to be. He did not think the hope was altogether a faint one, when they had regard to the wonderful expansion of the belief in Mr Ruskin and his principles which had taken place. (Applause.)”

After such a rallying speech it is little wonder that the resolution was carried unanimously.

Baker then proposed that Messrs Rydings of Laxey and Walker of London be appointed auditors. He also proposed that Robert Somervell (1851-1933) of the Kendal shoemaking family be appointed honorary secretary pro tem. and Edward Barnard, apparently a mill-owner in Wandsworth, seconded the motion. Several other formal resolutions were then passed. The meeting ended with a paper by Henrietta Carey (1844-1920) describing a charitable movement in Nottingham with which she was intimately connected that was “in harmony with the Guild”. The report was not reproduced, and although a copy was later sent to Walkley where apparently it was quickly lost.

“TO SEE YOU. NICE”: WHO ATTENDED THE GUILD’S FIRST GENERAL MEETING?

Aside from the ten Companions already mentioned—Baker, Barnard, Carey, Chamberlain, Fletcher, Graham, Guy, Hunt, Rydings, and Swan—who else is known to have been present at that first general meeting of the Guild?

Newspaper reports suggest that between twenty and thirty Companions of the Guild attended the meeting. The papers name five more: Ruskin’s publisher, George Allen (1832-1907), of Orpington; sculptor, Benjamin Creswick (1853-1946), by this time resident in Bewdley, but originally a Sheffield knife-grinder, and later one of Birmingham’s foremost art teachers; the landscape gardener, Joseph Forsyth Johnson (1840-1906), of Belfast; Emily Swan (1835-1909), “curatress” of the museum at Walkley (as Ruskin called her), and wife of Henry Swan; and George Thomson (1842-1921), the Huddersfield woollen manufacturer.

Most of these figures are well-known to students of Ruskin’s influence and historians of the Guild, but it is worth singling out Joseph Forsyth Johnson (pictured above), at this time the curator of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Belfast, but from the mid-1880s an important landscape architect of American parks. Ruskin was a huge influence on his approach to the natural landscape. In his first book, The Natural Principle of Landscape Gardening: Of the Adornment of Land for Perpetual Beauty (1874) he wrote that “the true poetic spirit and feeling which breathe in [Ruskin’s] pages possess an irresistible charm for every true lover of Nature”(p. ii). (A famous great grandson is the popular entertainer, Bruce Forsyth (1928-2017).) I dedicate this blog to a great grandchild of another of the Companions who attended the Guild’s first general meeting: to my dear friend, Annie Creswick Dawson, a Companion of considerable artistic sensitivity whose great grandfather, Benjamin Creswick, did so much to promote Ruskinian values in his work as an artist-craftsman and teacher.

The Guild’s minutes give the names of a further four Companions’ who were present:

- the poet, Katherine Harris Bradley (1846-1914) (named but not previously identified as present): she would become one half of the pseudonymous aunt-and-niece aestheticist, Michael Field, and her relationship with Ruskin and the Guild will be explored in a forthcoming blog;

- John Edwards Fowler (1842-1901), an engineer’s pattern-maker and self-nurtured man of literary taste who was a founding member of the Liverpool Ruskin Society in 1883;

- Annie Esther Somerscales (1842-1928), the daughter of a master mariner and a member of an artistic family, who was a remarkable schoolteacher in Hull; and

- Silvanus Wilkins (1828-1912), a Midlands banker with connections to the Co-operative Movement, and the probable reason that the Guild held its accounts with the Staffordshire Joint Stock Bank, of which he was general manager until 1883.

Mark Frost has also unearthed evidence that William Harrison Riley (1835-1907), the radical socialist who was in charge of the Guild’s estate at Mickley, also attended. A total of 20 Companions.

BIRMINGHAM’S LIBERAL ELITE

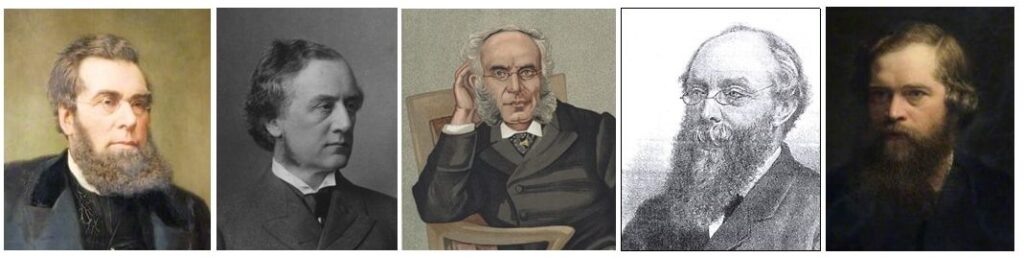

Given that Chamberlain and Baker were eminent Birmingham Liberals, it should come as no surprise that among their friends and colleagues in attendance at the first Guild meeting were members of the city’s pioneering Liberal elite, many of them figures of national note. Their presence at this important event in the Guild’s history has never previously been remarked upon by Ruskin scholars. Among them were (pictured left-to-right, below):

- John Skirrow Wright (1822-1880), button manufacturer and inventor of the postal order, a founding member of the Birmingham Liberal Association in 1865 and its first chairman, and in 1877 the first treasurer of the National Liberal Federation—tragically, he died on the evening of his election as MP for Nottingham (15 April 1880);

- Joseph Powell Williams (1840-1904), of the Worcester family of vinegar manufacturers, a leading Liberal councillor, an honorary secretary to the Birmingham Liberal Association, and later MP for Birmingham South (1885-1904);

- Francis Schnadhorst (1840-1900), draper and Liberal politician, honorary secretary of the Birmingham Liberal Association (1867-1884) and of the National Liberal Federation (1877-1893);

- William Harris (1826-1911), the architect and surveyor, journalist and author, Liberal politician and strategist; dubbed the “father of the Caucus” (the tightly controlled administrative structure he devised for running the Liberal Party in Birmingham), and the first Chairman of the National Liberal Federation (1877-82); and

- John Alfred Langford (1823-1903), chairmaker, Liberal, and self-taught journalist, poet, antiquary, and teacher. He was the first secretary of the Birmingham Co-operative Society, and—like Chamberlain—a follower of the Unitarian preacher, George Dawson (1821-1876), father of the “Civic Gospel”.

Please send feedback to contact@stuarteagles.co.uk