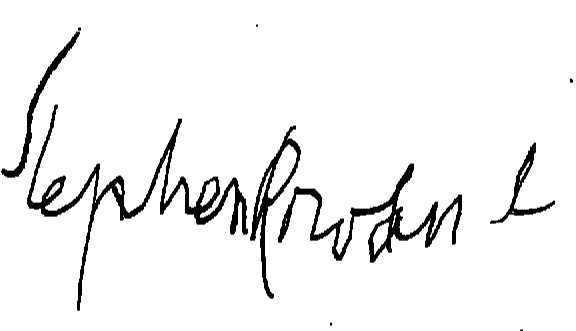

It is one of the unaccountable facts of Ruskin scholarship that many of John Ruskin’s keenest admirers have barely registered in the histories of his influence. A notable example is Stephen Rowland (1841-1940) (pictured below), an early and long-serving Companion of Ruskin’s Guild of St George, which celebrates its 150th anniversary this year. Rowland, the Ruskinian shopkeeper, was the civic saint of Cranleigh, in Surrey, sometimes described as the largest village in England. When he died at the grand old age of 99½ in 1940,* he had been a Companion for well over half a century.

The Ruskinian Shopkeeper:

Stephen Rowland, Civic Saint of Cranleigh

Stuart Eagles

{To download as a PDF, click here.}

To my friend, Dr James S. Dearden MBE,

a scholar and a gentleman,

on his 90th birthday.

[All colour images © Stuart Eagles]

“Cranleigh’s grand old man”, Rowland’s obituary in the Surrey Advertiser asserted, was the “pioneer […] to whose foresight the village owes much of its development” (12 October 1940). It is certainly true that, to a considerable extent, Cranleigh owes its expansion and modernisation in the late nineteenth century to the draper, shopkeeper, and municipal pioneer who counted Ruskin as a key inspiration. Rowland’s biography deserves to be added to the Guild’s chronicles, and historians of Cranleigh would be well served by an understanding of what Ruskin meant to him.

FAMILY AND VILLAGE LIFE

Rowland was a member of a family which traced its Unitarian roots to the seventeenth century. He was born on 5 April 1841 in Ditchling, Sussex, to William Rowland (1810—1898) and his wife, Lucy, neé Knight (1813—1888). William was a man of many parts—a master baker, grocer, schoolmaster, coachman, and gardener according to successive censuses, and a carpenter when Stephen got married. Stephen was the eldest of eight children who grew up in a house on West Street, Ditchling. His move to Cranleigh can be precisely dated to 4 May 1857 when, at the age of 16, he started work as an assistant to his uncle, Henry Rowland (1801—1870), a grocer and draper.

In the next few years, the village underwent rapid change. A community hospital—the first of its kind—was opened in 1859, and the railway station in 1865. In the same year the Surrey County School (now Cranleigh School) was founded to educate the sons of local farmers. Rowland later served the hospital as a manager and correspondent to the general committee. He was also a Vice-President of the League of Mercy, established in 1899 to recruit volunteers to help tend the sick and suffering in community hospitals; Rowland’s involvement came about at the personal invitation of the Liberal politician Pandeli Ralli (1845—1928), a Surrey County Councillor, a former MP, and a resident of Cranleigh.

On 26 October 1869 Stephen married Mary Gammon (1847—1925) at St Nicholas’s Church, Cranleigh. Mary was the daughter of a local coachman, publican and brewer, Phelp Gammon (1812—1891), who ran the White Hart. (On Christmas Day 1880, Mary’s sister, Emily Gammon (1859—1949) married Stephen’s brother, Peter Rowland (1852—1905), who helped him in the running of the shop.) Stephen and Mary had two sons and four daughters together. They lived most of their lives at Yew Tree House (pictured below), which was specially built for them on Ewhurst Road. A public presentation was made to celebrate the couple’s golden wedding anniversary in 1919.

THE SHOPKEEPER

Rowland’s uncle retired in the late 1860s and moved to Horsham, leaving the shops for his nephew to run. An industrious and energetic young man, Stephen rapidly extended the range of goods on sale. In 1871 he employed one man and one boy, but by 1881 his staff had expanded to include five men and two boys. Rowland’s shop operated as an outfitter, general store and Post Office rolled into one. In 1884 he advertised “Boots, Hats, Hosiery, Ready-made Clothes and Useful Drapery” all sold on the “Ready-money system” [West Surrey Times (26 April 1884)]; a “Clothier, Draper, and Grocer”, selling “useful Goods, bought from the best manufacturers for cash”. [West Surrey Times (7 May 1887).]

A report in the Surrey Advertiser describing Cranleigh’s Christmas Fair in 1880 noted that Rowland’s shop “as usual [excelled] in [the] variety and attractiveness of [its] display”: one of the “spacious windows” was “set out with the finest of fruits, and the choicest of wines and spirits, the other with fancy and useful articles of drapery, &c., in much request at this season of the year” (25 December 1880).

MUNICIPAL PIONEER, LOCAL DEVELOPER, CIVIC SAINT

As Rowland became more successful in business, he took a keener interest in the wider affairs of the village. Being the main local land agent he sought to develop Cranleigh as a residential centre which combined the public amenities of a progressive city with the peace, quiet and natural beauty of rural life. In 1876 he took a leading role in the formation of the village gas company which supplied homes with dependable heating and lighting. He served as a director for 43 years and for a long time was chairman, retiring in 1920. He helped establish a company in 1885 to improve the public water supply. The eight miles of mains piping was lagged with felt or flannel to prevent freezing in the winter, and the valves and hydrants were reportedly inspected every day.

In 1891 he converted the upper floor of two of his stores at the west end of Ewhurst Road, next to his home at Yew Tree House, turning it into the Village Hall. It was later occupied by the British Legion and is now a block of flats called Legion House. His original shop is now the Fettling Room. The Village Hall was described as “a lofty and well ventilated building, capable of holding 200 persons”. [Sussex Agricultural Express (11 July 1891).] The area, where the High Street, Horsham Road and Ewhurst Road meet, is known locally as Rowland’s Corner, and Rowland Road, a short distance away (pictured below), is named after him.

In 1894 Rowland led in the purchase of the New Park Estate (now the Woodlands Estate) situated between the Horsham and Ewhurst Roads. He planned it as a housing development supplied with mains water, gas and sewerage. Four new roads were built. New Park Road, Avenue Road, and Bridge Road, . all leafy and 40 feet wide at Rowland’s insistence. These tree-lined streets were distinguished by a growing number of substantial and attractive houses of character boasting large gardens. One of them—Ramsbury, on Bridge Road (pictured below)—became the Rowlands’s final home.

In 1896 an insurance company offered Rowland the manorial rights over Cranleigh Common. He took the proposal to the Parish Council which made the purchase for £250.

From 1908 to 1918 Rowland served as a member of Hambledon Rural District Council. He was also a member of Hambledon Board of Guardians, and a parish councillor in Cranleigh. From 1883 to 1907 he was people’s warden at St Nicholas’s Church (pictured below). “In 1929”, reported the Surrey Advertiser, “an illuminated address and a cheque were presented to Mr Rowland as a new year’s gift in recognition of his long and valued public services” (12 October 1940).

Increasingly immobile, he nevertheless continued to take an interest in village affairs until shortly before his death. His wife, Mary, had died at their home, Ramsbury, on 30 July 1925. Rowland lived another 15 years and died on 7 October 1940. Both were buried in St Nicholas’s Churchyard.

ROWLAND AND RUSKIN

According to Rowland’s obituary in the Surrey Advertiser, he had “much interesting correspondence” with Ruskin. That is probably so, but little of it has survived. What remains shines a light on Rowland’s Ruskinian philosophy, and reveals the value Ruskin attached to Rowland’s insights.

It is not clear precisely when Rowland became a Companion of Ruskin’s Guild of St George, but it was certainly in Ruskin’s lifetime, though apparently after 4 December 1884 when a Roll of Guild Companions was published. Rowland’s interest in the Guild endured until his death. He is also listed as an unattached member of the Ruskin Reading Guild which subscribed to a birthday address presented to Ruskin on the occasion of his 70th birthday in 1889.

The earliest evidence of a correspondence between them dates from 1880. A letter Rowland wrote Ruskin appeared in Fors Clavigera (1871-84), Ruskin’s monthly letters to the workmen and labourers of Great Britain. Rowland’s letter was dated 26 May, and appeared in Letter 89 (September 1880), reproduced in the Library Edition of Ruskin’s Works (vol. 29, pp. 415-416). This is evidently at least Rowland’s second letter to Ruskin, to which he responded. The earlier exchange is not known to have survived.

“REVERED SIR,—You ask me how I came to be one of your pupils. I have always been fond of books, and in my reading I often saw your name; but one day, when reading a newspaper account of a book-sale, I saw that one of your books fetched £38 for the five volumes [evidently Modern Painters (1843—60)] :I was struck with the amount, and thought that they must be worth reading; I made up my mind to find out more about them, and if possible to buy some. [T]he next time I went to London I asked a bookseller to show me some of your works: he told me that he did not keep them. I got the same answer from about half-a-dozen more that I tried; but this only made me more determined to get them, and at last I found a bookseller who agreed to get me Fors.

“When I got it, I saw that I could get them [direct] from Mr [George] Allen [Ruskin’s friend and publisher]. I have done so; and have now most of your works.

“I read Fors with extreme interest, but it was a tough job for me, on account of the number of words in it that I had never met with before; and as I never had any schooling worth mentioning, I was obliged to look at my dictionaries pretty often: I think I have found out now the meanings of all the English words in it.”

On that theme, later in the letter he asks Ruskin for the meaning of a word he had come across in the works of Thomas Carlyle, “Adscititious” (something additional, supplementary, but not integral); he had not been able to find it in any dictionary.

Rowland asserts boldly, “I got more good and real knowledge from Fors than from all the books put together that I had ever read.” Ruskin’s pride in such praise may be inferred from the fact that he published this first part of Rowland’s letter, but the substance is in what follows. “I am now trying”, Rowland told him, “to carry out your principles in my business, which is that of a grocer, draper, and clothier; in fact, my shop is supposed by the Cranleigh people to contain almost everything that folks require.” He continued:

“I have always conducted my business honestly: it is not so difficult to do this in a village as it is in larger places. As far as I can see, the larger the town the worse it is for the honest tradesman. [Ruskin’s Italics.]

“The principal difference I make now in my business, since I read Fors, is to recommend hand-made goods instead of machine-made. I am sorry to say that most of my customers will have the latter. I don’t know what I can do further, as I am not the maker of the goods I sell, but only the distributor.”

Rowland then writes, “If I understand your teaching, I ought to keep hand-made goods only, and those of the best quality obtainable.” Ruskin notes here, “By no means, but to recommend [hand-made good] at all opportunities.” This reply must have pleased Rowland, for his letter goes on to explain that if he sold only hand-made goods,

“I certainly should lose nearly all my trade; and as I have a family to support, I cannot do so. No; I shall stick to it, and sell as good articles as I can for the price paid, and tell my customers, as I always have done, that the best goods are the cheapest.”

He then adds, “I know you are right about the sin of usury. I have but little time to-day, but I will write to you again some day about this.” It would be fascinating to read such an exchange, but no such letters appear now to exist, if indeed they were ever written.

Rowland ends his letter of 26 May, “I sent the minerals off yesterday packed in a box. I am half-afraid now that you will not think them good enough for the Museum”. Ruskin explains to readers that this refers to a “collection of English minerals and fossils presented by Mr Rowland to St George’s Museum, out of which I have chosen a series from the Clifton limestones for permanent arrangement.” [Works 29.416n.] St George’s Museum, in Walkley, Sheffield, was founded by Ruskin in 1875 to bring beauty into the lives of the artisan. The collection (now in Sheffield’s Millennium Gallery) includes copies of paintings by the Old Masters, original watercolour drawings by Ruskin and his students, plaster-casts of the outstanding features of some of Europe’s most important buildings, coins, illuminated medieval manuscripts, great works of literature and fine natural history studies (particularly botany and ornithology, but also entomology, conchology and ichthyology) and—among other things—a large variety of precious stones and minerals of the kind Rowland donated.

In May 1885, Rowland evidently sent more specimens not noted in the Library Edition of Ruskin’s Works. In a letter in a private collection, Ruskin thanked him for his presents of African minerals for the St George’s Museum, “several being of great interest and all instructive. I have sent them to be arranged for the Museum by our acting mineralogist Francis Butler who will report to you on the specimens […]” Ruskin greatly respected Francis Butler, who was a well-known dealer in minerals operating out of Brompton Road, South Kensington. Ruskin had told the Principal of Whitelands [Teacher Training] College in Chelsea, Rev. J. P. Faunthorpe, “The honest and obliging mineralogist Mr Francis Butler, who will probably from this time be my chief caterer, lives at 180 Brompton Road, within easy call of you, and I should think might sometimes give the girls an informal lecture which would greatly help them” [Works 37.509]. Sadly, there is no record of any report by Butler on Rowland’s gift.

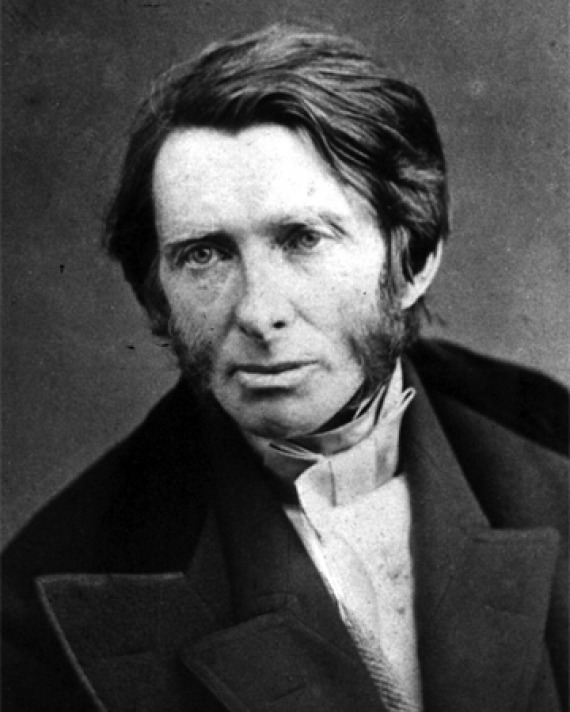

Ruskin (pictured above) and Rowland’s correspondence certainly endured, and on 15 March 1887, Ruskin wrote from Brantwood to the Pall Mall Gazette, with “Some Notes on the Land Question” (17 March 1887, p. 13) reproduced in Ruskin’s Works (vol. 29, pp. 598-599). “In looking over the material which the discontinuance of Fors Clavigera prevented my using”, Ruskin writes, “ I have come on the enclosed, to my mind, every way sensible and thoughtful letter, entering into close detail respecting recent errors in land management, which I thought might—under [the] present condition of [the] land question—be permitted space in your columns”. What follows, Ruskin told readers, was written by “Mr Stephen Rowland of Cranleigh”:

“I saw in last Fors that you are going to write on the land question. I therefore send you word what a good many farmers here think is the cause of their present difficulties. I daresay it is not different from what you know about the matter, but I thought it would do no harm to write. In the first place, some few years ago some manufacturers and others who had made large fortunes in trade came into the country and bought farms, or hired them at much higher rents than had ever been paid before. This led to a rise in rents all through the district. Well, then, the new farmers gave their labourers more money for their work than anybody else had ever done; but the worst of it was that, the masters not knowing themselves what a fair day’s work was, the men gradually did less and less work, and what they did was worse done than it used to be, until now it takes two men to do what one did in the old time. The farmers say, though, that there are still a few men who have always done, and do, their very best, and put their heart into their work, but there are but few such now.

“The new farmers soon had a new house or two built about the farm, and then compelled the parish to make the old green lanes—for which this country is famous—into hard roads, at a great expense and consequent increase in the parish rates, which are paid chiefly by the farmers. Then the Education Act was passed, which keeps the boys off the land until they pass a certain standard in the school. By the time they do this most of them don’t want to drive plough, but get into some other employment that they think is more genteel, so that the farmer has to pay a man instead of a boy to drive plough, and has also to pay the greater part of the boy’s schooling although he wants him more than enough on the farm. To make matters worse, the seasons have been against the farmers. They also tell me that the tithes are higher than they used to be: why this should be I cannot understand, but it seems that when tithes were taken in kind, every tenth shock of corn was taken, whether the shock was good or bad, and so a fair average tenth was got, but now the tithe is calculated on the market price of corn, and as the farmer always sends his best corn to market, and keeps what he calls the trail corn at home to feed cattle and pigs with, the tithe is really levied on the best corn only, and not on the good and bad together, as it used to be. There is also the game difficulty, and the imports from foreign countries, which you most likely know a good deal more about than I do; but, right or wrong, most farmers that I have talked to about these matters think as I have written. I forgot to tell you, though, that there is one farmer here who never uses a machine for anything that he can get done by hand. He has told me that he would have his corn threshed with a flail if he could get any one to do it. He says that the straw is better for cattle.”

Ruskin adds nothing further, nor do Ruskin’s editors, nor the PMG. Neither shall I, except to note that while the language of the letter marks it apart from today’s debates, the points at issue remain stubbornly enduring. Rowland’s words would re-pay careful consideration. He raises questions to which we should one day return.

Let’s finish, though, with a letter to Rowland from Ruskin, written on 28 January 1885, which was reproduced in Ruskin’s Works (vol. 37, p. 513). It is particularly interesting for the same reason that it survives. Rowland sent the original of this letter to the Editor of the Daily Telegraph, to be sold for their Shilling Fund, established to benefit the widows and orphans of the soldiers of the Highland regiments (19 April 1900). (The Telegraph reported on 8 May (p. 6) that the letter raised 20 shillings.)

“MY DEAR SIR,—It is quite true that the Highland Regiments are now probably only half Highland—more’s the pity. But their spirit and power is Highland absolutely. You could make nothing in the least like them of any Lowland race. For the Irish, see the Duke of Wellington’s own testimony in preface to Capt. [William Francis] Butler’s Far-Out Rovings Retold [(1880)].—Faithfully yours, J. RUSKIN.”

*[Although Rowland was the oldest Companion of the Guild when he died in 1940, aged 99½, Mary Hope Greg (1850—1949) would outlive him by just two weeks at the end of the decade.]

Please send feedback to contact@stuarteagles.co.uk